He had dozed off in the chair because he awoke to her voice. She was on her side, her head propped on her arm. He couldn’t tell how much time had passed. She seemed in better shape than him. “I’m not sure this makes sense,” she said. His head cleared immediately; what had come before this pronouncement? What didn’t make sense?

“I’m not blaming you,” she said. She picked up the saltcellar and fidgeted with it. “Perhaps I’m skeptical of love in general.”

He wanted to tell her she was young for such an attitude, but thought it would sound judgmental. When instead he wanted to touch her.

She laid her head back on her pillow, and stared at the glass piece as she turned it over. “Love is no different than any other relationship. At its core, it seems to be more about power.”

Was it not obvious that she had all the power? “I couldn’t disagree with you more,” he said.

She turned toward him. Again with her hand under her head. She was utterly divine for all of her disarray. “At the very moment I fall in love with you, you will cease to be captivated by me.”

She could imagine loving him! He should be overjoyed by this. But she had been hurt before. Perhaps by Mandelstam. Possibly himself. There were lesser men who’d be enthralled with her until their dying breaths. Let her find one of that species, she seemed to be saying. Let her be with one for whom she was never intended.

She smiled then, and it was as if to break his heart. “Isn’t this the way it tends to work for you?” With other women, she meant. She’d added this last part carefully, not wanting to hurt him.

“Come to my reading tomorrow,” he said.

She looked surprised. He put his hand to his heart. He could feel it knocking.

Her face seemed to empty of all expression. She asked how she could say no. Later he would wonder if she’d actually expected an answer to her question.

Bulgakov arrived at the apartment of the playwright, Alexei Glukharyov, early the following evening. Glukharyov met him at the door, half-dressed and apologizing that there were no spirits to be had. He insisted he’d forgotten though Bulgakov guessed that it was his wife who was not completely approving of these get-togethers and had scotched the idea, who’d wisely predicted that hosting an evening of liquored-up writers would end at a much later hour. Bulgakov told him he’d invited someone. He then sat on the sofa and waited for others to arrive. He had one cigarette remaining. It would calm his nerves, but he feared smoking it too soon. Perhaps someone would think to bring a bottle and he stared at the door as though he could will this to happen. A roll of pages was pressed between his shirt and suit pocket. He’d been unable to decide what to read, uncertain of what she might like, and he vacillated between telling himself it mattered not at all and that his future happiness depended on this choice. Glukharyov had disappeared behind the curtain that hid the bedroom; he was arguing with his wife. At some point in their past they’d found sufficient interest in one another to register their union, to sign the required documents. Was love an elusive thing or this banality? Was it as Margarita had predicted? More writers arrived; one had brought wine and glasses were passed. Perhaps she wouldn’t come; then he could read anything.

Chairs, cushions, an ottoman, and the sofa were arranged in a rough circle. When these were filled, the rest sat on the floor. Lights were dimmed save one and it was beside this that each writer would stand, the illuminated page drawing all eyes like a torch. Four had brought pieces that evening. The press of bodies, the room made smaller by its dark corners, provided the gathering with a sense of propitiousness. Theirs was art; each had a special duty to listen. Glukharyov provided a short introduction for each reader, fanciful and humorous, and the air stirred with short bouts of laughter and applause, as Glukharyov revealed (then demonstrated) how the first, a poet, had been a former actor who’d been forced to give up the stage because of narcolepsy. Another had been a member of the first expedition to the South Pole. Tragically, the Norwegian herring had given him terrible gas and the Vikings sent him home before achieving their destination. In such ways, these lucky ones had escaped the grip of fame. Bulgakov watched Glukharyov’s wife in the shadows. She laughed as the others did, and he imagined how she might see her husband anew and remember the initial spark of faith that had caused her to slip her hand in his. It would feel like taking another breath.

Bulgakov was the final reader. As the applause for the one preceding diminished, Glukharyov stood to give his preamble, only Bulgakov wasn’t listening. Margarita had not come and it seemed a well of disappointment had closed around him. He tried to imagine any number of reasons. His instructions had been poor; her illness had worsened; yet he felt it was none of these. She was alone in her apartment. She was aware of the time and the place. She had found some way to say no.

Glukharyov’s introduction was different from the others. He took up a volume of Gogol and began to read. It was the opening paragraphs from Dead Souls and the arrival of Chichikov, Seliphan, and Petrushka to the provincial town of N—. He was an excellent reader and took his time over the winding passages. Bulgakov knew these words well and it seemed as though Glukharyov and perhaps all in attendance knew of his disappointment, and it was in this way that they sought to arouse him from it.

Gogol himself would speak to Bulgakov, his voice reaching across the decades. Do these words sound familiar, he went. Like a coat one might don? Dare you—dare you?

Indeed! In his later years Gogol had become convinced that God had abandoned him. Tortured, half-crazed, he burnt his remaining manuscripts only days before he died. As though the promise of man’s redemption must perish with him. He claimed the Devil had tricked him into doing so. He’d been only forty-one.

Glukharyov closed the book and, extending his hand toward Bulgakov, welcomed him forward. “Follow that!” he said. The command was spoken with admiration. The expectation of the room seemed to lift him to his feet.

Under the light, Bulgakov unfolded his pages. From the darkness, one laughed. “Bulgakov will keep us until breakfast.” He shook his head—no, no. He was still uncertain what to read. His opening chapter was likely of the best quality. Further, there was the scene of his burgeoning romance with the Margarita of his story. Of this he was less certain; he might have read this had she come, but even then questioned this strategy. Now in her absence, he could set this aside.

The door opened and Margarita appeared. She slipped past the others and took the empty seat on the sofa. She struggled to remove her light jacket; the woman beside her helped, and she folded it across her lap and clasped her hands on top of it. Another voice called from the shadows. “Are you going to read something tonight or are we only to appreciate the spectacle of your dumbfounded wonder?” Even Margarita smiled in the warm room, dropping her eyes a little.

She’d come! He rifled through his pages again. He could impress her with the wit of his satire, his knifelike caricature. The idiocy of entrenched Moscow; the amusements of the Devil’s entourage. She would be dazzled for his genius. She was watching him, waiting with the others, her eyes shining.

In 1931 when Gogol’s body was exhumed he was discovered to be facing downward. The writer had had a terrible fear of being buried alive, so much so that he’d willed his casket be fitted with a breathing tube as well as a rope by which to sound some external bell if needed. Sadly, such wishes were viewed as the paranoia of a madman and were not implemented.

Gogol’s voice came back to him. Did you know I had a terrible infatuation of Pushkin? I called him my mentor but I wished he was otherwise. He had a most beautiful chin. I dreamt of taking it into my mouth. Alas, his life’s purpose was to catch a bullet with his spleen. I only wanted love. Is it possible that is all any of us desire?

Bulgakov began to read.

“One hot spring evening, just as the sun was going down, two men appeared at Patriarch’s Ponds…”

At its conclusion, his audience sprang from their seats, the applause was explosive. Margarita seemed to have been swallowed in their midst. He searched for her even as he was repeatedly thumped on the back, congratulations pummeling his ears. Where was she? Then he saw her! Glukharyov had pulled her to the side and was speaking intently. Bulgakov studied his lips but the voices around him were overwhelming. Yet she was there, watching Bulgakov as she listened, as though he was the only person in the room.

What was Glukaryov saying? He seemed overly serious, his hand on her arm, unwilling to spare her his prognostication. Would he convey some warning? Persuade her to look askance at writers? She looked anxious and Bulgakov parted the crowd, stepping over furniture, trying to make his way toward her. Only then did Glukharyov’s words find him—dangerous writing. Not so, Bulgakov wanted to protest. Then, so much worse—foolish risk. It was too late. He came up to them ready to drive Glukaryov into the wall.

“Well?” said Bulgakov, breathless for his emotions.

Glukharyov shook his hand; he seemed not to register Bulgakov’s acute dismay. “Great work, great work.” He leaned in. “My friend, you realize it’s not publishable.” His face was gathered in concern and apology.

Bulgakov’s exhilaration crested with this. Should he believe that Glukaryov was expert in such things? Should she believe him? Did she think she might be better off with a lesser writer? She could not! What was the point of all of this if it didn’t matter?

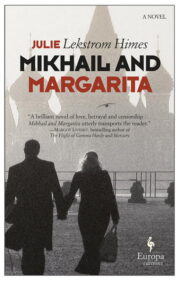

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.