‘My brother Patrick is a computer wizard,’ the girl said. ‘Most of the time, he’s a nerd, but he is tops on computers.’

‘Will he be there tonight?’

‘Yeah.’

‘And will Greg?’

Alison shrugged. ‘No one ever knows what Greg is going to do.’

‘I see,’ Kate said dryly. ‘Well, I’m looking forward to coming to dinner with your parents. They seem so nice.’

‘They are, I suppose.’ Alison finished her coffee and put the mug down. ‘I’m going. Do you want to come with me?’

The challenge in her eyes was hostile again and suddenly Kate was tired of the child. ‘I’ll be ready in about half an hour,’ she said. ‘If you want to wait for me, that’ll be nice, if not, I’ll follow you over later.’

For a moment Alison hesitated, obviously reluctant to walk back alone, then with an exaggerated sigh she flung herself down in one of the chairs. ‘OK. I’ll wait.’

‘Thanks.’ Kate smiled. She gathered up the mugs and left the girl sitting there.

The door to the spare room was open and the boxes and cases in there had been strewn all over the floor. Kate stared at the scene for a moment in dismay, then she turned and called down the stairs. ‘Alison, did you do this?’

‘What?’ The girl’s voice was puzzled.

‘Do all this? For God’s sake!’ Her case, the case with the torc was still locked, she could see that from the doorway.

Alison ran up behind her and looked round. ‘What a mess.’

‘All these boxes and things. I left them tidy.’

‘Oh.’ Alison avoided her eye. ‘Well, it wasn’t me. How could it have been? I haven’t been upstairs at all.’

Kate found her heart was hammering rather too loudly in her chest. There had to be an explanation. This child or her brother must have done it. Perhaps while she was on the beach Greg or the unknown computer wizard had sneaked in and messed up the place. Turning, she flung open her bedroom door. Nothing in there appeared to have been touched. Everything was as she had left it.

Seeing her white face Alison frowned. She too suspected that it must have been Greg. Last time she had seen him, he had still been planning to try to scare Kate out of the cottage. He was keen on her idea of making Kate think it was haunted. Could he have done all this? Had he already taken things this far? Staring round she felt herself shiver. If it was him, then it was working. She narrowed her eyes for a moment. Was it Greg down on the beach as well? Was he behind what had happened yesterday?

Suddenly she was furious. She turned and running down the stairs she opened the front door. ‘Come on. I need to get home,’ she called. ‘There’s nothing wrong. Let’s go.’

If it was Greg she would get even, if it was the last thing she ever did. The bastard! The unmitigated, double dealing, swindling bastard! He had really scared her. And he owed her a new radio cassette player.

XIX

‘You shouldn’t have come.’ Nion took her hands. ‘You take too many risks. What if you were seen?’

She broke free and ran a few steps in front of him to the edge of the water, skipping like a child. ‘Who is there to see? He’s out all day. The slaves are too busy to care. The child and his nurse think I am visiting my sister.’ She pirouetted, laughing. ‘I’ve never been so happy. I can’t believe this is happening. Me, a staid Roman matron, and you -’ she stood in front of him, staring into his face and rested her hands for a moment on the folds of his cloak, ‘- you, a prince of the Trinovantes.’

Nion laughed, throwing back his head, his strong teeth white in his tanned face, the laugh lines at eyes and mouth carving deep into the square features.

Around them the dunes stretched for miles; sand, spun and blown by the wind into hollows and ridges, the shingle thick and clean as the tide drew back. Nearby, her mule waited patiently beside the horse, which stood between the shafts of his chariot, grazing listlessly on the salt sand flowers and grasses. They were alone. Quite alone. He caught her against him, burying his face in her hair.

‘I want you to come away with me. One of my brothers is in the west. We could go to him there. Your husband would never find you.’

She tensed, raising her face slowly to his and he read the conflicting emotions in her eyes. Desire. Hope. Excitement. All three blazed in their sea-grey depths, but there was doubt there too. Doubt and fear. ‘I can’t leave the boy.’

‘Then we’ll take him with us.’

‘No.’ She shook her head sadly. ‘No. He would never allow his son to go. Me -’ she hesitated. ‘I don’t know if he would come after me, but he would search the whole earth for his son.’ Her eyes brimmed with tears. ‘And I could not ask you to leave this – your home.’ His land, his woods, his pastures, his fields, his water, the salt pans which made him rich, all worked by the men of his people.

She shivered as she looked up again and raised her lips towards his. His gods were powerful, cruel, demanding. Sometimes she wondered if they had given their blessing to their servant’s union with a daughter of Rome, or if they were jealous, biding their time, waiting to punish her for her presumption.

Behind them the sun glittered on the sea, turning it the colour of jade. As his hands moved down to release her girdle she forgot her fear; she forgot everything, drowning in the pleasure of his touch.

‘We’ll have to give you a season ticket at this rate!’ The man in the ticket office at the museum greeted Kate with a cheery smile.

She smiled back. ‘I think you might. Or a job!’ She was still wondering why she was here. Was it the thought of the next book, bubbling uncontrollably in her subconscious, or was it just the fascination of that strange, half-excavated pit on the beach beside her cottage? She refused to admit that she felt a slight reluctance to stay in the cottage alone. She could not allow that. But perhaps it was a little of all three. She was feeling guilty. She shouldn’t be here. She should be working with George Byron and his irritating, hysterical mother.

Retracing her steps upstairs she went to stand once more in front of the statue of Marcus Severus, gazing into his face as if somewhere there in the cold, dead eyes she would find the answer to her riddle. For he had something to do with that grave on the shore, she was sure of it. Marcus Severus Secundus and Augusta, his wife. Thoughtfully, she turned to the display case where his bones lay exposed to view. There was no answer there. Nothing but the gentle hum of the lights and in the distance, the muffled and unreal shouts and screams of the video replay of Boudicca’s massacre.

As she parked the car in the barn later she glanced at Redall Farmhouse with a certain amount of longing. They were there this time; she could see smoke coming from the chimney and there were lights on in the kitchen. They were expecting her to supper; supposing she knocked and went in now? Perhaps she could help prepare it, or sit out of the way by the fire sipping tea or better still whisky, until the appropriate time. But she couldn’t, of course she couldn’t. She glanced at her watch. It was barely three o’clock. She had another five hours to wait before she could knock on their door.

Shouldering her bag she turned up the track into the woods. The early sunshine had gone. The sky was growing increasingly wintry and as the wind rose a quick light shower of sleet raced through the trees. She shivered. At least the fire was ready to light at home.

Home. She hadn’t thought of the cottage as home before, but for now that’s what it was. She could draw the curtains against the coming darkness, have tea and a hot bath and do a couple of hours work before setting out on the walk back through the dark.

Opening the door she dumped her bag on the floor and glanced round, unconsciously bracing herself against signs that anyone had been inside. There were none. The cottage was as she had left it. The kitchen was spotless, the doors and windows closed and the air smelt faintly of burned apple wood. Relieved, she unpacked her shopping and went to light the woodburner, then slowly she went upstairs.

Pulling open her cupboard she looked through the clothes she had brought with her. Since she had arrived in north Essex she had worn trousers and thick sweaters, but she wanted to change into something a little more formal tonight. More formal, but still practical, bearing in mind that she had a long walk through the muddy woods. She pulled out a woollen skirt and a full sleeved blouse and threw them on the bed.

It was then that she remembered her promise to Alison to photograph the grave. She glanced at the window. It would soon be getting dark and the sky was already heavy with cloud. Perhaps she could leave it until tomorrow. But she wanted to keep her promise. She needed to win the girl’s trust, for the sake of what was left of the site. She hesitated for a moment longer, then reluctantly she went to find her camera. She loaded a new roll of film and with a wistful glance at the fire she grabbed her anorak and set out into the cold.

The beach was very bleak. Turning up her collar, she put her head down into the wind and walked as swiftly as she could back towards Alison’s dig, firmly resisting the urge to glance over her shoulder at the coming darkness. The wind had blown the sand into soft ridges, rounding the sharp corners, drying the surface of the soil so the different strata were harder to see. Squinting against her hair which whipped free of its clip into her eyes she raised the camera and peered through the viewfinder. She doubted if anything would come out even with the flash, but at least she would have tried. She took the entire roll, shooting the dig from every angle, and trying, rather vainly, to get a few close-ups of the sand face itself. She did not see the dark, withered stumps which had been a man’s fingers; nor the black protrusion which was his femur, broken and splintered and already crumbling back into the sand.

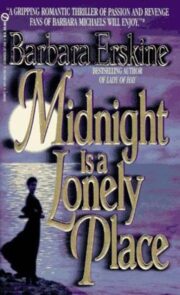

"Midnight is a Lonely Place" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Midnight is a Lonely Place". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Midnight is a Lonely Place" друзьям в соцсетях.