‘I am learning things,’ I said defensively. ‘Things I need to know.’

Will nodded, tolerant. ‘Good,’ he said. ‘If you are sure you need them.’

‘I do,’ I said firmly, and he nodded and said no more.

We rode together as old friends, talking when we wanted, silent most of the time. He rode well. His horse Beau could never match the speed and stamina of Sea who was a full-bred hunter. But he could give us a good race and if we gave them a ten- or twenty-yard start we were sometimes hard-pressed to catch them before the winning post.

Will said little, but we never passed working people or a newly planted field without him ensuring that I knew exactly what they were doing. Whenever we passed anyone in the lane, or working on a hedgerow or digging a ditch, we would pull up and Will would introduce them by name, or remind me when I had met them before. Watching him with these people I could tell he was well liked and, despite his youth, respected. The older men deferred to his judgement and reported to him, the younger men were pleasant and easy with him. I guessed that they teased him about his rides with me; but when I was there they were respectful and easy. The young women stared at me, taking in every detail of my clothes and boots and gloves. I did not mind. I had stood in the centre of a show ring when coins and flowers were thrown in at my feet. I was hardly likely to blush because half a dozen girls could not take their eyes from the golden fringe on my jacket. I saw more than one of them glance at Will with an intimate special smile and I guessed he was popular with the young women too.

We passed two girls on the lane who called, ‘Good day,’ to me and flicked smiling eyes at Will.

‘You’re a favourite,’ I said dryly.

‘You know those two, remember?’ he asked. ‘They’re the Smith girls. They live in the cottage opposite the forge. The Smith’s daughters, they call him Littl’un.’

‘Yes,’ I said diverted. ‘Why does everyone call him that? He’s hardly little!’

Will smiled. ‘His real name’s Henry,’ he said. ‘His ma died while she was giving birth to him and he was real small and puny when he was a child, always ailing. No one thought he’d live, so no one took the trouble to give him a name of his own. They called him for his brother. Then, when Julia Lacey started setting the village to rights again, her Uncle John the doctor took special care of him and he grew strong. He survived but the nickname stuck.’

I nodded. Even in the names of people you could trace the power that the owners of the land had over the people who worked it. There was the compliment that women of twenty and older were named Julia, after my mother, and there were several Richards in the village and a little crop of Johns. But the blacker side was the children who had not been named at all during the hungry years when my family had ruined the village with their greed. During those years children were given nicknames or the same names as their brothers and sisters. It was so unlikely that they would all survive. And the graveyard had many little mounds with blank headboards of wood, where there had been no money to have stone carved or, in the despair of hunger, nothing anyone wanted to say.

‘Very few children die in Acre now,’ Will said, accurately reading my thoughts. ‘Very few. Of course they get ill, and of course there are accidents. But no one dies of hunger on your land, Sarah. The way we run the estate means that everyone has a share of the wealth, and that is enough to feed everyone.’

We turned the horses up the little lane which leads up to the top of the Downs. I could ride it now with confident familiarity.

‘It will have to change,’ I said evenly. ‘When I am of age, I will change it.’

Will smiled at me, and reined back so that I could go ahead of him up the narrow track. ‘Maybe you’ll change first,’ he said. ‘Maybe you’ll come to see that to live on a land where people are well fed and where they have responsibility for their own work is a greater pleasure than a little extra money. The land is farmed well, Sarah, don’t forget that. But it is not farmed at the expense of the people who work it.’

‘I’ve no time for passengers,’ I said. I was glad Lady Clara could not hear my voice which was harsh and flat. ‘In this new century it is a different world. There are great markets overseas, there are huge fortunes to be won or lost. Every farm in the country has to compete with every other one. If you give in to your workforce you are fighting with one hand tied behind your back.’

I drew up to let him come alongside and I saw the sudden heat of anger go across his face.

‘I know you have been taught to speak how the landlords speak,’ he said and his voice was very controlled. ‘But all of you will have to learn that the wealth of a country is its people. You won’t be able to produce much wealth with a half-starved workforce. You won’t be able to make machines and tools with a workforce which cannot read or write. You will make a little profit for a short time by working everyone as hard as you can and paying them a little. But who will buy the goods if the working people have no money?’

‘We’ll sell abroad,’ I said. We had reached the top of the Downs and I pointed to where the sea was a slab of clear blue, shading to violet at the horizon. ‘We’ll sell to native countries, all around the world.’

Will shook his head. ‘You’ll do the same things there as you do here,’ he said. ‘You and your new-found friends. You’ll buy cheap and you’ll sell dear. You’ll overwork them and you’ll underpay them. When they revolt you’ll bring in the army and tell them it’s for their own good. You’ll refuse to educate them and then you’ll say they can’t be trusted because they’re so ignorant. You’ll keep them underfed and ignorant and dirty and then complain that they smell different or that they cannot talk properly. You’ll do to them what you’ve done to working people in this country!’

He paused. I said nothing.

‘It won’t work,’ he said quietly. ‘You’ll never be able to keep it up. The native countries will throw you out – oh yes, and your cheap whisky and bad cottons with you. The working people of this country will insist on their rights – a vote, a right to decide who governs them. Then it will be estates like Wideacre which will show people the way ahead. Places like this which have tried sharing the wealth.’

‘It’s my wealth,’ I said stubbornly. ‘It’s not the wealth.’

‘Your land?’ he asked. I nodded.

‘Your people?’ he asked.

I hesitated, uncertain.

‘Your skies? Your rain? Your birds? Your winds? Your sunshine?’

I turned my head away from him in sudden irritation.

‘It doesn’t work,’ he said. ‘Your idea of ownership makes no sense, Sarah. And you should know that. You have lived on the very edge of the society right on the borderlines of ownership. You know that out there the world is full of things which nobody owns.’

I shrugged. ‘It’s because I was out there that I’ll call it my land,’ I said sourly. ‘You don’t know because you’ve never been that poor. You’ve slept soft and ate well all your life, Will Tyacke. Don’t tell me about hardship.’

He nodded at that. ‘I forgot,’ he said spitefully. ‘We are all to be punished for your misfortune.’

Then he turned his horse and led the way across the top of the Downs in a day so sweet and sunny and fine that I was angry with myself for calling up the old feelings of being robbed and abused, even now; when I should be glad that I had won through.

He let it go, he was too kind to harangue me when I looked as I did then: hurt, and angry and confused. Instead he demanded an outrageous long start in a race, claiming, with no cause, that Beau was threatening to cast a shoe and would be slower. Instead he took off like a whirlwind and I had to bend low over Sea’s neck and urge him on to his top gallop to catch Beau before he reached the thorn tree which acted as our winning post at the top of the Downs.

We reached there neck and neck and we pulled up with a shout – Sea just a nose ahead.

‘I think he’s getting faster!’ I said, all breathless with my hair tumbling down and my hat askew.

‘It’s the practice he’s getting,’ he said, smiling at me. ‘I never rode races before.’

‘I wish you could have seen Snow,’ I said, careless for a moment. ‘I wish you could have seen Snow. He is an Arab stallion, an absolutely wonderful white colour and Robert can do anything with him. He can count, and choose coloured flags out of a jar. And he can rear and dance on his hind legs. Robert is teaching him to carry things in his mouth like a dog!’

‘Robert?’ Will said, his voice carefully neutral.

‘A friend I once had,’ I said flatly. Something in my voice told him I would say no more so he merely smiled.

‘I wish I had seen him too,’ he said. ‘I love good horses. But I’ve never seen a grey to match this one. Where did you get him, Sarah? Did you have him from a foal?’

I hesitated then, wary. But the day was too warm, and the song of the larks was beguiling. Far below me I could see the little village of Acre as snug as a toy village on a green carpet. The patchwork of fields, green and yellow with their different crops told of the easy wealth of my estate. The thick clumps of darker green were the trees of the parkland around my home, my house, Wideacre.

I smiled. ‘I won him!’ I said, and as Will listened I told him how I had first seen Sea and how he had been called unridable. How I had persuaded my master to let me ride him (a horse-trader he was, I said), how he had started the book and made hundreds of guineas from the bet. Will laughed and laughed, a great open-hearted bellow, at the thought of me hitching up my housemaid skirts and getting astride Sea. But he went quiet when I told him how Sea reared and plunged at the end and threw me down.

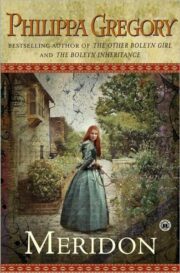

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.