I nodded. Dandy was still waiting on the little board, I could see it swaying in the air currents at the roof of the barn.

‘She’ll need to hear you,’ he said. ‘You’d better tell her you’re all right.’

‘Very well,’ I said, surly. ‘I’ll tell her.’

Dandy’s pale distant face peered at me from the side of the platform, looking down to where I stood far, far below her.

‘All right, Dandy,’ I called up. ‘I’m all right now. I’m sorry. You jump if you want to. Or come down the ladder if that’s all you want to do today. You’ll never hear me try to stop you again.’

She nodded and I saw her hook the trapeze towards her.

‘I’ve never seen you cry before,’ Jack said wonderingly. He put a hand up to touch the tears on my cheek but I jerked my head away.

It didn’t stop him. ‘I didn’t think you were girl enough for tears, Meridon,’ he said. His tone was as soft as a lover.

I shot him a hard sideways look. ‘She’ll never hear me call her down again,’ I promised. ‘And you’ll never see me cry again. There’s only one person in the whole world I care for, Jack Gower, and that’s my sister Dandy. If she wants to swing on the trapeze then she shall. She won’t hear me scream. And you’ll never see me cry again.’

I turned my shoulder on him and looked up to the roof of the barn. I could not see Dandy’s face. I did not know what she was thinking as she stood there on that rickety little platform and looked down at us: at the fretwork of the brown rope catch-net, the white wood shaving floor, and our three pale faces staring up at her. Then she snatched the bar with a sudden decision and swooped out on it like a swallow. At precisely the centre of its return, at the very best and safest place, she let go and dropped like a stone, falling on to her back into the very plumb centre of the net.

There were hugs all around at that, but I stood aloof, even fending Dandy off when she turned to me with her face alight with her triumph.

‘Back to work,’ David called, and set us to exercises again.

Jack was ordered to hook his legs over the bar on the wall and practise trying to haul his body up so that it was parallel with the ground. I worked beside him, hanging from my arms and pulling myself up so that my eyes were level with the bar and then dropping down again in one fluid motion.

Dandy he lifted up to the trapeze and set her to learning the time to beat again.

Then we all took a short rest and swapped around until dinner-time.

Robert Gower came into the kitchen when we were at our dinner and took Mrs Greaves’s seat at the head of the table, a large glass of port in his hand.

‘Would you care for one of these, David?’ he asked, gesturing to his glass.

‘I’ll take one tonight gladly,’ David replied. ‘But I never drink while I’m working. It’s a rule you could set these young people, too. It makes you a little bit slow and a little bit heavy. But the worst thing it does is make you think that you are better than you are!’

Robert laughed. ‘There’s many that find that is its greatest advantage!’ he observed.

David smiled back. ‘Aye, but I’d not trust a man like that to catch me if I were working without a net beneath me,’ he said.

Robert sprang on that. ‘You use cushions in your other show,’ he said. ‘Why did you suggest we try a net here?’

David nodded. ‘For your own convenience mostly,’ he said. ‘Cushions are fine for a show which is housed in one place. But enough cushions to make a soft landing would take a wagon to themselves. I’ve seen a net used in a show in France and I thought it would be the very thing for you. If they were using the rings, and just hanging, not letting go at all, you could perhaps take the risk. But swinging out and catching, you need only be a little way out, half an inch, and you’re falling.’

The table wavered beneath my eyes. I took my lower lip in a firm grip between my teeth. Dandy’s knee pressed against mine reassuringly.

‘I’ve worked without cushions or nets,’ David said. ‘I don’t mind it for myself. But the lad I was working with died when he fell without a net under him. He’d be alive today if his da hadn’t been trying to draw a bigger crowd with the better spectacle.’ He looked shrewdly at Robert Gower. ‘It’s a false economy,’ he said sweetly. ‘You get a massive crowd for the next three or four nights after a trapeze artist has fallen. They all come for the encore, you see. But then you’re one down for the rest of the tour. And good trapeze artists don’t train quick and don’t come cheap. You’re better off with a catch-net under them.’

‘I agree,’ Robert Gower said briefly. I took a deep breath and felt the room steady again.

‘Ready to get back to work?’ David asked the three of us. We nodded with less enthusiasm than at breakfast. I was already feeling the familiar ache of overworked muscles along my back and my arms. I was wiry and lean but not all my humping of hay bales had prepared me for the work of pulling myself up and down from a bar using my arm muscles alone.

‘My belly aches as if I’ve got the flux,’ Dandy said. I saw Robert exchange a quick smile with David. Dandy’s coquetry had lasted only as long as her energy.

‘That’s the muscles,’ David said agreeably. ‘You’re all loose and flabby, Dandy! By the time you’re flying I shall be able to cut a loaf of bread on your belly and you’ll be as hard as a board.’

Dandy flicked her hair back and shot him a look from under her black eyelashes. ‘I don’t think I’ll be inviting you to dine off of me,’ she said, her voice warm with a contradictory promise.

‘Any aches, Jack?’ Robert asked.

‘Only all over,’ Jack said with a wry smile. ‘It’s tomorrow I’ll stiffen up, I won’t want to work then.’

‘Merry won’t have to work tomorrow,’ Dandy said enviously. ‘Why’re you taking her to the horse fair, Robert? Can’t we all go?’

‘She’ll be working at the horse fair,’ Robert said firmly. ‘Not flitting around and chasing young men. I want her to watch the horses outside the ring for me and keep her ears open, so I know what I’m bidding for. Merry can judge horseflesh better than either of you – actually better than me,’ he said honestly. ‘And she’s such a little slip of a thing no one will care what they say in front of her. She’ll be my eyes and ears tomorrow.’

I beamed. I was only fifteen and as susceptible to flattery in some areas as anyone else.

‘But mind you wear your dress and apron,’ he said firmly. ‘And get Dandy to pin your cap over those dratted short curls of yours. You looked like a tatterdemalion in church yesterday. I want you looking respectable.’

‘Yes, Robert,’ I said demurely, too proud of my status as an expert on horseflesh to resent the slight to my looks.

‘And be ready to leave at seven,’ he said firmly. ‘We’ll breakfast as we go.’

8

We went to Salisbury horse fair in some style. Robert Gower had a trim little whisky cart painted bright red with yellow wheels and for the first few miles he let me drive Bluebell, who arched her neck and trotted well, enjoying the lightness of the carriage after the weight of the wagon. Mrs Greaves had packed a substantial breakfast and Robert ate his share with relish and pointed out landmarks to me as we trotted through the little towns.

‘See the colour of the earth?’ he asked. ‘That very pale mud?’

I nodded. There was something about the white creaminess of it which made me think of Wide. I felt as if Wide could be very near here.

‘Chalk,’ he said. ‘Best earth for grazing and wheat in the world.’

I nodded. All around us was the great rounded back of the plain, patched with fields where the turned earth showed pale, and other great sweeps where the grass was resting.

‘Wonderful country,’ he said softly. ‘I shall build myself a great house here one day, Meridon, you wait and see. I shall choose a site near the river for the shelter and the fishing, and I shall buy up all the land I can see in every direction.’

‘What about the show?’ I asked.

He shot me a smiling sideways glance and bit deep into the crusty meat roll.

‘Aye,’ he said. ‘I’d always go with it. I’m a showman born and bred. But I’d like to have a big place behind me. I’d like to have a place so big it bore my name. Robert Gower, of Gower’s Hall,’ he said softly. ‘Pity it can’t be of Gowershire; but I suppose that’s not possible.’

I stifled a giggle. ‘No,’ I said certainly. ‘I shouldn’t think it is.’

‘That’ll give my boy a start in life,’ he said with quiet satisfaction. ‘I’ve always thought he’d marry a girl who had her own act, maybe her own animals. But if he chose to settle with a lass with a good dowry of land he’d not find me holding out for the show.’

‘All his training would have been done for nothing then,’ I observed.

‘Nay,’ Robert contradicted me. ‘You never learn a skill for nothing. He’d be the finest huntsman in the county with the training he’s had on my horses. And he’ll be quicker witted than all of the lords and ladies.’

‘What about Dandy and me?’ I asked.

Robert’s smile faded. ‘You’ll do all right,’ he said not unkindly. ‘As soon as your sister sees a lad she fancies she’ll give up the show, I know that. But with you keeping your eye on her and me watching the gate, she won’t throw it away for nothing. If she goes into some rich man’s keeping then she’ll make a fortune there. If she marries then she’ll be kept too. Same thing, either way.’

I said nothing but I was cold inside at the thought of Dandy as a rich man’s whore.

‘But you’re a puzzle, little Merry,’ Robert said gently. ‘While you work well I’ll always have a place for you with my horses. But your heart is only half in the show. You want a home but I’m damned if I can see how you’ll get one without a man to buy it for you.’

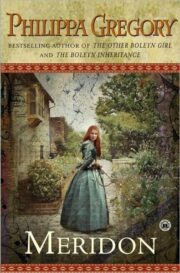

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.