‘I’ll have the show when he is too old to travel,’ he said with confidence. ‘Every penny he saves now goes into the show, or goes into our savings. We’ll never be poor again. He’ll see to that. And anything he says I should do…I do. And anything he says he needs…I get. Because it was him and one bow-backed horse that earned us food when the whole village was starving. No one else believed he could do it. Just me. So when he took the horse on the road I went with him. We didn’t even have a wagon then. We just walked at the horse’s head from village to village and did tricks for pennies. And he traded the horse for another, and another, and another. He is no fool, my da. I never go against him.’

Dandy said not a word. We were both spellbound by Jack’s story.

‘How was he a hard man?’ I asked, going to the central question for me. How he would treat us, how he would treat Dandy if the tide of luck started going against us? ‘Did he used to hit you? Or your mother? Did she travel with you too?’

Jack shook his head and bent down so that Dandy and I could lift the screen on to his back. He walked with it towards the wagon, dragging it behind him, and then he came back.

‘He’s never raised his hand to me,’ he said. ‘He never laid a finger on my ma. But she didn’t believe in him. He left her and the three little ones in the village and went on the tramp with the horse. He’d have left me behind too but he knew I was the only one that believed he could do it. He had me trained to ride on the horse within days. I was only a littl’un and I was scared of nothing. Besides, it’s a very big horseback when you’re only five or six. It was easy to stay on.

‘At the end of the summer we went home. He’d been sending money back when he could. And after the winter we started out again. This time there was a cart we could borrow. Ma wanted to come too, but Da was against it. But she cried and said she needed to be with him. I wanted her. And Da wanted the little ones along with him. So we all went on the road.’

Jack stopped. Then he bent for the final section of screen and loaded it in silence. Dandy and I said nothing. He came back and picked up a couple of halters and slung them towards the wagon. He turned and went for the gate as if the story was over.

We went after him.

‘What happened then, Jack?’ I asked. ‘When you were all travelling together?’

Jack sighed and leaned on the gate, looking across the field as if he could see the wagon and the woman with the two small children and the baby at the breast. The man walking with his son at the horse’s head, the horse which he had trained to dance for pennies.

‘It was a grand season,’ he said. ‘Warm, and sunny. A good harvest and there was money about. We went from fair to fair and we did well at every one of them. Da had enough money to buy the cart and then he exchanged it for a proper wagon. Then he saw a horse he fancied and bought her. That’s Bluebell that we have now. He saw she had a big enough back for me as I grew bigger. And she’s steady.

‘We had two horses then so we didn’t work the street corners any more but we took a field and started to take money at the gate. I had an act jumping from one horse to another, and through a hoop. I was still quite small you see – I must have been about seven or eight.

‘Ma was on the gate, and the little babbies sold sweets that she made to the audience. We were making good money.’

He stopped again.

‘And?’ Dandy prompted.

Jack shrugged. Shook the past off his shoulders with one quick movement and then a long stretch. ‘Oh!’ he said wearily. ‘She was just a woman! Da saw Snow and wanted to buy him. Ma wanted to go back to the village with the money we’d made and settle down and Da go back to cartering.

‘They argued about it – night and day. Da wanting Snow with all his heart and promising Ma that he’d make his fortune with the horse. That she’d have a cottage of her own and a comfortable wagon for travelling. That we’d move up in the world. He knew he could do it with Snow.

‘Ma couldn’t win the argument. She didn’t understand the business anyway. So she went to a wise woman and got herself a brew from the old witch and then told Da – pleased as punch – that she was pregnant and that there would be no money for Snow. And that she would not give birth to a child on the road but that they would have to go home.’ Jack smiled, but his dark brown eyes were like cold mud. ‘I can remember her telling him: “I’ve caught you now,”’ he said. ‘She got a belly on herself to trap him.’

‘What did your da do?’ I asked.

‘He left her,’ Jack said briefly. ‘All this happened at Exeter, our home was outside Plymouth. I never knew if she got herself home. Or the babbies. Or what happened to the one she had in her belly. He took the money he had been saving and bought Snow and we moved the next day. He wouldn’t let her in the wagon though she begged and cried and my brothers and sister cried too. He just drove away from her, and when she tried to get up on the step he just pushed her down. She followed us along the road crying and asking him to let her in, but he just drove away. She only kept up for a mile or so, she had the little ones and they couldn’t walk fast. And she was carrying the babby, of course. We heard her calls getting fainter and fainter as she fell further and further behind.’

‘Did you ever see her again?’ I asked, appalled. This calculated cruelty was worse than any of Da’s drunken rages. He would never have left Zima so, whatever she had done. He would never have pushed Dandy and me off the step of the wagon.

‘Never,’ Jack said indifferently. ‘But don’t you forget that if my da can do that to his wife of fifteen years, who bore him four children and had his fifth in her belly, he can certainly do it to you two.’

I nodded in silence. But Dandy was angry.

‘That’s awful!’ she exclaimed. ‘Your ma most likely had to go on the Parish and they’d have taken her children away from her. She was ruined! And she had done nothing wrong!’

Jack swung up into the wagon and started stowing blankets and bedding for the journey.

‘He thought she’d done wrong,’ he said from the dark interior. ‘That’s enough for me. And she was cheating, getting a belly on her like that. Women always cheat. They won’t do a straight deal with any man. She got what she deserved.’

Dandy would have said more, but I touched her on the arm and drew her away from the step, around to the back of the wagon to help me hump feed.

‘I can hardly believe it!’ she said in a muttered undertone. ‘Robert always seems so nice!’

‘I can believe it,’ I said. I was always more wary than Dandy. I had watched Jack’s unquestioning obedience to his father; and I had wondered how that round-faced smiling man could exert such invisible discipline.

‘Just remember not to cross him, Dandy,’ I said earnestly. ‘Especially at Warminster.’

She nodded. ‘I’m not going to be left on the road like his wife,’ she said. ‘I’d rather die first!’

That odd shudder, which I had felt when Jack started talking about his mother, put icy fingers down my spine again. I put out my hand to Dandy. ‘Don’t talk like that,’ I said, and my voice was faint as if it were coming from a long way away. ‘I don’t like it.’

Dandy made an impudent laughing face at me. ‘Miss Misery!’ she said cheerily. ‘Where are these buckets to go?’

It was sunset before we were packed and ready to leave – the sudden red sunset of autumn. Bluebell was between the shafts, her head nodding with pretended weariness. Jack was in his working breeches and smock. He was going to ride Snow the stallion, who was too valuable to be tied for a long journey like the ponies. He offered me the ride, but I was tired and felt lazy. If Robert did not order me to drive the wagon I would lie in my bunk and doze.

‘You’re getting as lazy as Dandy,’ Jack said to me in an intimate undertone as we tied the ponies in a string at the back of the wagon. Da’s little pony had settled down with the others and went obediently into line.

‘I feel idle today,’ I confessed, not looking up from the halter I was knotting.

His warm hand came down over my fingers as I tied the rope, and I looked up quickly to see his face, saturnine in the twilight.

‘What do you dream of in your bunk, Meridon?’ he asked softly. ‘When you lie in your bunk and daydream and the ceiling is rocking above you. What d’you dream of then? Do you think of a lover who will take off your clothes, strip those silly boy’s breeches off you, and kiss you and tell you that you are beautiful? Don’t you dream of a clean bed in a warm room and me, lying in bed beside you? Is that what you think of?’

I left my hand under his warm clasp and I met his eyes with my steady green gaze.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I dream that I am somewhere else. That my name is not Meridon. That I do not belong here. I never dream of you at all.’

His handsome dark face turned sulky in an instant. ‘That’s twice you’ve said that,’ he complained. ‘No other girl has ever turned away from me, not ever.’

I nodded fairly. ‘Then chase them,’ I said. ‘You’re wasting your time with me.’

He turned on his heel and left me abruptly. But he did not go back to the lighted wagon. I nearly bumped him as I came around the wagon with a hay net to hang on the side. He had been leaning against the wagon, brooding.

‘You’re cold, aren’t you?’ he accused. ‘It is not that you don’t like me. I’ve just been thinking. Dandy smiles at the old gentlemen and they chuck her under the chin and give her a ha’penny. But you never smile, do you? And now I think of it, I’ve never seen you let anyone touch you except Dandy. You don’t even like men to look at you, do you? You won’t come out to cry-up the show with me because men might look at you and desire you, and you don’t like that, do you?’

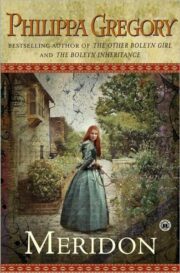

"Meridon" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Meridon". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Meridon" друзьям в соцсетях.