I turned my face a little, that she might not see the downward tilt of my mouth; I need not have worried; she was intent on Gwennan Menfrey’s vivacious face in the looking glass.

“Oh yes, Bevil has had countless love affairs. He always will, I suppose. He’s like Papa. But there’s always one they go back and back to, and for him it’s Jess.”

“And what about Jess herself? Is she going to be waiting patiently for him to come back?”

“Of course. You’ve seen Bevil, haven’t you? He has the Menfrey fascination.”

I laughed. “But not the Menfrey conceit, I hope.”

“Conceit! My dear Harriet, is it conceit to face the truth? Would you have me pretend that I was plain and insignificant? What good would that do?”

“None at all, for you could never be able to convince people that you thought so. Your arrogance is the most convincing thing about you.”

“Pah!” she said. “And I'll tell you something I’ve told you before, Harriet Delvaney: If you were less anxious to make it clear to people that you are unattractive, they might possibly remain unaware of it.”

“At least,” I said, “I do not put myself hi the indelicate position of being engaged to one man and dallying with others.”

“My dear Harriet, I shall shortly settle down at a very early age. Don’t you think I’m entitled to sow a few wild oats?”

“When one sows, one is often obliged to reap.”

“Oh, very clever and also very trite. I seem to have heard those sentiments expressed about three thousand times during a life-time, which you must admit could scarcely be called a long one.”

“Gwennan, are you in love with Harry Leveret?”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she said and changed the conversation.

Gwennan finished her year abroad before I finished mine.

When she went home I missed her very much. And three months later I myself returned.

My stepmother was pleased to see me. She told me that she felt lonely in the house without my father. “Perhaps,” she said wistfully, “I’m not the right mistress for a house like this. I’ve often thought I’d like a little place in the country,”

“Why don’t you give it up then?” I asked. “Why not find a little place in the country?”

She looked at me incredulously. “You wouldn’t mind, Harriet!”

I laughed at her. She was really rather engaging.

I went through the house. It seemed different now that my father was no longer there. I stood before his portrait in the library, contemplating it It was lifelike, but it was not the father whom I bad known. The eyes were almost benign. They had never looked like that for me. The smile was amused, the eyes alert A man who had charm for all except his daughter.

Upstairs I went; I leaned over the banisters, sniffing the smell of beeswax and turpentine and remembering what I had heard that night when I ran away. I had come a long way from that little girl who had believed herself to be ugly and unwanted because someone had carelessly said she was. Gwennan told me that I was always on the defensive, and she was right. Bevil only had to show me some attention and I bloomed into a new personality; I had only to wear a dress which had belonged to a Menfrey woman, and I became attractive.

The Menfreys were changing me—Gwennan with her often brutal frankness, Bevil with his admiration. I often wondered, though, whether Bevil’s tenderness to me was the kind he gave to every woman. He was very attractive to women; he showed how much he admired women, how important they were to him; and while he was in love with beautiful Jessica Trelarken, he could find time to be kind to plain Harriet Delvaney.

Once it had been thought that I should marry Bevil— but would that be changed now? For it seemed that my father had left his money to Jenny, and that I, although well provided for, was not the heiress it had once been thought I should be.

I received a letter from Gwennan.

“My dear Harriet, the wedding day is fixed. I’ve told them that I will have no one but you for my bridesmaid—at least, one of them; and you are to be the chief. Maid of honor, I believe, is the correct term. You are to come down here … at once … or as soon as you can arrange it. Don’t delay. There’s so much to do, and I’ve such lots to tell you. Mamma wanted to bring me to London for an orgy of spending, but that is quite out of the question. Money, my dear! It’s a sad convention that the bride’s family have to undertake all the expenses of the marriage. I’m not a rich man’s wife yet. After the honeymoon—it’s to be Italy, my love, and then Greece—you shall be our first guest at Chough Towers. I’ve told Harry, and he is ready to give way to me in all things. I intend that it shall remain so all our lives. Come as soon as you can, for there is the matter of your wedding garments, my dear. They will have to be made in Plymouth—but I am sure we can concoct something together quite spectacular.

“Menfrey stow is in a whirl of excitement about it, and, believe me, the main topic of conversation is The Wedding. It’s seven weeks away, but there is a great deal to do, and if you don’t come soon we shall never get you fitted for that magnificent wedding garment. Bevil is most enthusiastic about the wedding. He’s fearsomely busy these days now that he has become the Member for Lansella. I think he’s secretly pleased because when I marry my dear rich Harry, there’ll be less obligation for him to make a m.o.c. (marriage of convenience). I know him well. If Jess were only as rich as my Harry, there would be a double wedding at Menfreya.

“Now I am being indiscreet. But when was I not? You must bum this letter as soon as you have read it, just in case it should fall in the hands of (a) Bevil, (b) Jess Trelarken, (c) just anybody but yourself.

“Come soon. I miss you. Gwennan.”

I wanted to be there. I wanted to feel the sea breezes on my face; I wanted to sleep in Menfreya and wake up in the morning to look out over the sea to the island house, which was ours–or, rather, Jenny’s—for everything seemed to be hers now.

I was seated at my window, looking over the square, when I saw the carriage arrive and Jenny alight, looking disturbed.

She was coming up the stairs to my room. “Harriet,” she called. “Are you there, Harriet?”

“Come in,” I replied and went forward to greet her. She looked bewildered, rather like a child who has been expecting a gift that has been snatched away.

“The country house …” she said.

“Yes?” I knew she had been excitedly looking for one for the last few weeks.

“I can’t have it”

“Why?”

“The money isn’t mine, after all.”

“Do explain.”

“You were there when they read the will. You couldn’t have understood it either,”

“I wasn’t listening, I suppose. I was thinking about my father and the past and his marrying you and all that.”

“I wasn’t listening either. I don’t understand it now, although he went over and over … explaining, and I said I did. He kept saying, ‘It’s in trust for Miss Delvaney.’ That’s you, dear. It’s in trust for you, which seems to mean that Tm having the interest or something while I live, but when I die it will be yours. No one else is to have it but us, you see. You have your income now and the money set aside for your education and marriage portion, and the rest is mine, but only for the income, and I’m not allowed to touch the capital. I can’t buy a house, because the money is all for you. In a way, I’ve been lent it till I die—to have the income from it; and after that, it'll be for you and no one else.”

“I begin to understand.”

So he had remembered me then; he had cared for my future more than I had believed, and doubtless it had occurred to him that my flighty little stepmother would be an easy prey for fortune hunters; and any who did not take the trouble to find out the terms of the will before marrying her would have a somewhat unpleasant shock when they did discover.

I was still a considerable heiress—or at least I should be if Jenny died.

My father was the sort of man to tie up everything very securely.

“I’m sorry about the house, Jenny.”

She smiled. “Can’t be helped, can it? I don’t mind it so much now you’re home.”

I was planning to go to Menfreya for Gwennan’s wedding, but a few days before I was due to leave for Cornwall I received a letter from Aunt Clarissa, who asked me to call at her house in St. John’s Wood.

Fanny accompanied me, because when visiting Aunt Clarissa one must observe all the conventions, and she would consider it unseemly for me to travel alone. My stepmother should have accompanied me, but she had not been invited and in fact told me that Aunt Clarissa had, since the marriage, made it quite clear that she bad no intention of calling on her or inviting her to call.

Fanny would take tea with my cousins' maid while I was with my aunt and cousins.

I was ushered into the drawing room, where my aunt was seated with two of my cousins—Sylvia and Phyllis. Clarissa, the youngest girl, was still in the schoolroom. Phyllis was about my age, and Sylvia two years older.

As I went in I was conscious of my limp and my hair, which would not curl.

“Ah, Harriet.” My aunt languidly held up her face that I might kiss her cheek. She did not rise, and the greeting was cold—no true kiss, the touching of our skins, that was all.

“Pray sit down. On the sofa there with Sylvia. Phyllis, my dear, you may ring for tea.”

Phyllis tossed back her yellow curls and went to the bell-rope. I was aware of three pairs of eyes on me—supercilious, critical, complacent eyes. “Thank heaven, my girls are not like this one,” said Aunt Clarissa’s eyes.

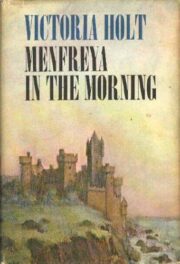

"Menfreya in the Morning" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Menfreya in the Morning". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Menfreya in the Morning" друзьям в соцсетях.