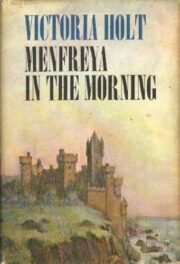

Victoria Holt

Menfreya in the Morning

1

To see Menfreya at its best was to see it in the morning. I discovered this for the first time at dawn in the house on No Man’s Island, when away to the east the scarlet-stained clouds were throwing a pinkish sheen on the sea, and the water which lapped about the island was like pearl-gray rippled silk.

The morning seemed more peaceful because of the night of fear through which I had passed, the scene more delightful because of my nightmares. As I stood at the open window, the sea and the mainland before me, with Menfreya standing on the cliff top, I felt as elated by all that beauty as by the fact that I had come safely through the night.

The house was like a castle with its turrets, buttresses and machicolated towers—a landmark to sailors, who would know where they were when they saw that pile of ancient stones. They could be silver-gray at noon when the sun picked out sharp flints in the walls and made them glitter like diamonds; but never did Menfreya look so splendid as when touched with the rosy glow of sunrise.

Menfreya had been the home of the Menfreys for centuries. I had secretly christened them the Magic Menfreys because that was how they seemed to me—different from ordinary people, striking in appearance, strong, vital people. I had heard them called the Wild Menfreys, and according to A’Lee—the butler at Chough Towers—they were not only wild but wicked. He had tales to tell of the present Sir Endelion. The Menfreys had names which seemed strange to me but not, apparently, to Cornishmen, for these names were part of the ancient history of the duchy. Sir Endelion had abducted Lady Menfrey when she was a young girl of not more than fifteen, had brought her to Menfreya and kept her there until her reputation was ruined and her family only too glad to agree to the marriage. “Not for love,” said A’Lee.

“Don’t make no mistake about that, Miss Harriet. It were the money that he were after. One of the biggest heiresses in the country, they say; and the Menfreys needed the money.”

When I saw Sir Endelion riding about Menfrey stow I thought of him as a young man, looking exactly like his son Bevil, abducting the heiress and riding with her to Menfreya — poor terrified girl, little more than a child, yet completely fascinated by the wild Sir Endelion.

His hair was tawny and reminded me of a lion’s mane. He still had an eye for the women, so said A’Lee; it was a failing among the Menfreys; many of them had come to grief —men and women—through their love affairs.

Lady Menfrey, the heiress, was quite unlike the rest of the family; she was fair and frail, a gentle lady who concerned herself with the poor of the district. She had meekly accepted her fate when she passed her fortune into her bus-hand’s bands. And with that, said A’Lee, he soon began to play ducks and drakes.

She proved to be a disappointment—apart from the money—for the Menfreys had always been heavy breeders, and she had only one son, Bevil, and then there had been a gap of five years before she produced Gwennan. Not that she had not made efforts in between. The poor lady had had a miscarriage almost every year, and continued to do so for some years after Gwennan’s birth.

As soon as I saw Bevil and heard that he was the image of what his father had been in bis youth, I knew why Lady Menfrey had allowed herself to be abducted. Bevil had the same coloring as his father and the most attractive eyes I had ever seen. They were of the same reddish-brown tint as his hair; but it wasn’t the color which made one aware of them. I suppose it was an expression. They looked on the world and everyone in it with assurance, amusement and an indifference as though nothing was worth caring deeply about. For me, Bevil was the most fascinating member of a fascinating household.

Gwennan, his sister, I knew best of them all, for she was my age and we had become friends. She had that immense vitality and the arrogance which appeared to be inherent. We used to lie on the cliffs among the sea pinks and gorse bushes and talk—or rather she talked and I listened.

“In St. Neot’s church there’s a glass window,” she once told me. “It’s been there for hundreds of years and on it there’s a picture of St. Brychan and his twenty-four children. There’s St Ive and Menfre and Endelient… . Menfre, that’s obviously us, and Papa’s name came from Endelient. And Gwennan was Brychan’s daughter; so now you know… ”

“And what about Bevil?”

“Bevil!” She spoke his name with reverence. “He’s named after Sir Bevil Granville, who was the greatest soldier in Cornwall. He fought against Oliver Cromwell.”

“Well then,” I said, knowing a little more history than she did, “he didn’t win.”

“Of course he won,” she retorted scornfully.

“But Miss James says the King lost his bead and Cromwell ruled.”

She was typically Menfrey; imperiously she waved aside Miss James and the history books. “Bevil always won,” she declared, and that settled it.

Now the walls of the house were changing color again; the rosy tint was fading and they were silvery in the bright dawn. I gazed at the outline of the coast, at the wicked rocks, sharp as knives and treacherous because they were so often covered by the sea. There was a range of rocks close to the island which were called the Lurkers. Gwennan said this was because they were often completely hidden from sight and were lurking in wait to destroy. any craft that came near them. No Man’s Island, a part of this chain of rocks, was about half a mile from the mainland and nothing more than a hump in the sea, being about half a mile hi circumference; but although there was only one house on it, there was a spring of fresh water, which, again said Gwennan, was the reason the house had been built there. There was some mystery about the house and a reason why no one wanted to live in it, which, I assured myself now, was a good thing; because if there had been a tenant, where should I have spent last night?

It was not a place I should have chosen had there been a choice. Now the house in which no one “wanted to live was filling with comforting light, but even so it was eerie, as though the past had been trapped here and resentfully wanted to catch you and trap you so that you belonged to it.

If I told that to Gwennan she would laugh at me, I could imagine the scorn in her high-pitched, imperious voice. “You! You’re too fanciful. It’s all because of your affliction.”

Gwennan had no compunction about openly discussing subjects which others pretended did not exist. Perhaps that was why I found her company irresistible, although at times it was hurtful.

I was hungry, so I ate a piece of the chocolate which Gwennan had brought for me, and looked about the room. At night the dust sheets had made ghosts of the furniture, and I had wondered whether I would prefer to sleep outside; but the ground was hard and the air chilly, and the noise of the sea, like murmuring voices, was louder and more insistent outside than in. So I had climbed the staircase to one of the bedrooms and lain fully dressed on the covered bed.

I went down to the big stone-floored kitchen; the flags were damp; everything was damp on the island. I washed hi the water I had drawn from the spring the day before; there was a mirror on the wall and as I combed my hair I gazed at my reflection, thinking that it looked different from what it did in my room at home. My eyes looked bigger; that was fear. There was a faint color in my cheeks; that was excitement. My hair was sticking out in all directions; that was because of a disturbed night. It was thick, straight hair that liked to be untidy—the despair of the numerous nannies whose unrewarding fate it had been to direct my childhood, I was plain, and there was no pleasure in looking at my image.

I decided to pass the time in exploring the house to assure myself that I really was alone. The strange noises which had tortured the night were the creaks of boards; the rhythmic advance and retreat of the waves, which could sound like breathing or whispering; or the scamper of rats, for there were rats on the island, Gwennan had said, which came from the ships wrecked on the Lurkers.

The house had been built by the Menfreys a hundred and fifty years ago—for like so much of the district the island belonged to them. There were eight rooms beside the kitchen and outhouses; and the place had recently been furnished, waiting for the tenant who could not be found.

I came into the drawing room with its casement window which looked out to sea. There was no garden, although it appeared that at some time someone had tried to make one. Now the grass grew in patches and there were gorse bushes and brambles everywhere. The Menfreys had not bothered with it and it was useless to, for at high tide the sea covered it.

Having no idea of the time, I came out of the house and ran down to the sandy cove, where I lay gazing at Menfreya and waiting for Gwennan.

The sun was climbing high before she came. I saw her in the cove, which belonged to the Menfreys and which, as a special concession, they allowed the public to use so that it would not be necessary to close part of the shore and force people to make a detour. Three or four boats were kept tied up there, and I watched her get into one and row over. In a short time it was scraping on the sand and, as she scrambled out, I ran to meet her.

“Gwennan,” I screamed.

“Ssh!” she answered. “Someone might hear you—or see you. Go into the house at once.”

She was soon with me, more excited than I had ever seen her; I noticed that she was wearing a cape inside which were enormous pockets, and these bulged with what I guessed to be the food she had promised me.

"Menfreya in the Morning" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Menfreya in the Morning". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Menfreya in the Morning" друзьям в соцсетях.