“Don’t set anything on fire,” she told him, and closed the door.

Then she walked through the stone arch on her right and almost ran into an ancient wood railing that ran around three sides of an open space. The railing rocked a little as she put her hands on it, so she looked over the edge carefully.

The opening dropped two stories down to a stone floor, empty in the growing darkness.

Okay, then, Andie thought, and made a circuit of the gallery, discovering doors that led into the nursery and into the servants’ stairwell. Then she went back to the little hall and to Alice’s room, where she knocked.

“Go away,” Alice said.

Andie went in and saw that Alice had changed into a too-large jersey T-shirt that hung down past her knees, clearly a hand-me-down from some adult. She looked both pathetic-poor little Alice had to get ready for bed on her own-and eerie-poor little Alice’s shirt said BAD WITCH on it in glowing green letters. She looked oddly defenseless without her armor of necklaces-they were hanging over her lampshade now-but with her white-blond hair standing out every which way, she also looked demented. We’ll comb that tomorrow, Andie thought.

“Sorry,” she told Alice. “I just wanted to say that if you need me, I’m on the other side of the nursery.”

“I won’t need you.” Alice got into bed and pulled her covers over her head.

“Right.” Andie noticed that Jessica had fallen to the floor. “You dropped something.” She bent and picked up the old doll and poked Alice under the covers.

“Hey!” Alice said, and then Andie pulled back the covers and handed her the doll.

“Good night,” Andie said, and Alice pulled her covers up over her head again.

“Yes, we’re going to be great pals,” Andie said, and headed back across the nursery to her own room, thinking that it was no surprise the nannies had cracked. They’d probably expected to be put living in the tomb at any moment, probably by Carter and Alice.

She heard something from the hallway by Alice’s room and went back to check. Alice’s door had come partly open, and inside Alice was talking.

“She’s not staying,” Alice was saying. “She’s just going to be here a month. She’s not even a nanny. It’s okay. We’re staying right here.”

Andie pushed open the door a little more, expecting to see Carter, and Alice looked around, alone in her room.

“I told you,” she began.

“Who were you talking to?”

“Nobody,” Alice said, turning her head toward the wall.

Imaginary friend, Andie thought, and said, “Okay.”

Then she turned to go and saw the white rocker at the end of the bed.

It was rocking.

She looked back at Alice, who met her eyes defiantly.

“What?” Alice said.

She did that, Andie thought, and said, “Nothing. Good night,” and closed the door, now in complete sympathy with the nannies who’d bolted.

Anybody with sense would.

Andie put the weirdness that was Alice and Carter out of her mind and spent the next hour unpacking and settling into her new room. It was surprisingly charming: white paneled walls and high, sculpted ceilings and long stone-lined windows covered with full, patterned draperies that clashed with the incongruously cheap silver-patterned black comforter that somebody with a lot of romance in her soul and no money in her checking account had bought to cover the large walnut four-poster bed. The rest of the furniture in the room was a mixture of styles probably inherited from different parts of the house as hand-me-downs, and the crowning touch was a cheap metal plaque over the bed that said ALWAYS KISS ME GOOD NIGHT. There was something a little obsessive about that which, given Andie’s surroundings, leaked over into creepiness. She put her pajamas on, brushed her teeth in the bathroom, put Kristin’s folder about the kids on the bed, and then, looking at the “Archer Legal Group” label on the folder, went to find her jewelry box. Buried at the bottom in a small manila envelope was her wedding ring, pretty and cheap, now painted and varnished to keep it from tarnishing again, the last thing she had left from her marriage. She should have thrown it out since it was worthless, but…

She slid the ring on her left hand and smiled in spite of herself, remembering North going crazy trying to replace it with a real gold ring that wouldn’t turn her finger green. Then she put the jewelry box away and was pulling back the covers when she heard a knock at the hall door and opened it to see Mrs. Crumb with a small tray. “A little cuppa before bed,” the housekeeper trilled, her red cupid’s-bow mouth smiling tightly, as she put the tray on the table next to the bed. “I got no problem bringing you up a cuppa every night since it’s only going to be a month?” She let her voice rise at the end, part question, part hope.

“Uh, thank you.” Andie eyed the tray doubtfully, but the yellow-striped teapot smelled richly of peppermint and there were violets painted on the big striped cup.

Mrs. Crumb nodded. “I put in a little liquor, too. You sleep good now.” She glanced down at the foot of the bed. “Sweet dreams.”

She retreated back through Andie’s door, and Andie closed it behind her and sniffed the pot. Minty. Very minty. She sat down on the bed and poured tea into the cup and then took a sip and got a full blast of at least two shots of peppermint schnapps. Whoa, she thought. The tea was good and peppermint was always nice, but unless Mrs. Crumb was trying to put her into a schnapps-induced stupor, the housekeeper had an exaggerated idea of “a little liquor.”

Maybe she should make her own tea.

She began to read Kristin’s notes, sipping cautiously. The kids’ mother had died giving birth to Alice, she read, their father had died in a car accident two years ago, and their aunt had died in a fall four months ago in June. And now, Andie thought, they’re alone with Crumb. And me. That thought was so harrowing that she forgave them the weirdness of their first meeting. Things would get better.

Poor kids.

She sipped more tea and read more notes. The three nannies had all said the same thing: the kids were smart, the kids were undisciplined, the kids were strange, there was something wrong, and they were leaving. Only the last one had tried to take the kids with her, and Alice had gone into such a screaming fit that she’d lost consciousness and the nanny had had to detour to a hospital. After that, the nanny took the kids back to Archer House and left them there. “These children need professional psychological help,” she’d written, and Andie thought, So North sent me.

That was so unlike him, not to send a professional, not to get a team of experts down there, and she thought, He’s not taking it seriously. Either that or he wanted her buried in southern Ohio for some reason.

She tilted her head back to think about that and saw the curtain of the window nearest the bed move, a flutter, as if from a draft. She watched, and when it didn’t move again, she shook her head and went through the rest of the folder, sipping the liqueur-spiked tea until the combination of that and the dry curriculum reports from the nannies made her so sleepy, she gave up. She turned off the bedside lamp, and the moonlight seeped into the room-full moon, she thought-and it was lovely to be so deeply drowsy on such a soft bed in such soft blue light that she let herself doze, thinking, I should have called Flo to tell her I arrived, I should have called Will, I should have…

Something moved in her peripheral vision, maybe the curtain again, she was pretty sure nothing had moved. Exhaustion or maybe the liqueur in the tea. She looked sleepily around the room, but it was just gloomy and jumbled, a gothic kind of normal, although it seemed colder than it had been, so she let her head fall back and snuggled down into the covers and drifted off to sleep, and then into dreams where there was shadowy laughter and whispering, and someone dancing in the moonlight, and as she fell deeper into sleep, the whispering in her ear grew hot and low-Who do you love? Who do you want? Who kisses you good night?-and she saw Will, smiling at her, genial and easygoing with his blond frat-boy good looks, and then she fell deeper and darker, and North was there, his eyes hot, reaching for her the way he used to, demanding and possessive and out of control in love with her, and she sighed in relief from wanting him, and somebody whispered, Who is HE?, and she went to him the way she always had-impossible to ever say no to North-and lost herself in him and her dreams.

Andie woke at dawn with a headache, which she blamed on Mrs. Crumb’s hot tea along with the hot dreams about North, probably evoked because she’d taken his name again. Guilt will always get you, she thought and resolved to stop lying, even if it was the only way to defeat Crumb. She took an aspirin and went down and moved the rest of her things from her car to her room, and then drove fifteen miles into the little town at the end of the road and hit the IGA there for decent breakfast food. Then she headed back to the house, determined to Make a Difference in the kid’s lives, but once there, she hit the wall. Alice was in the kitchen demanding breakfast, but she didn’t want eggs or toast or orange juice. Alice wanted cereal. She’d had cereal the day before and the day before that and the day before that and today wasn’t going to be any damn different. Andie looked into Alice’s gray-blue eyes and saw the same stubbornness that had defeated her in her short marriage.

“You’re an Archer, all right,” she said and gave Alice her cereal.

Then she made ham and eggs for Carter on the stubborn old stove, thinking of the kitchen North had remodeled for her when she’d moved into his old Victorian in Columbus, of the shining blue quartz counters and soft yellow cabinets and the open shelves filled with her Fiesta ware. It’d been her favorite place in the world, next to their bedroom in the attic. This kitchen was like a meat locker. Very sanitary but…

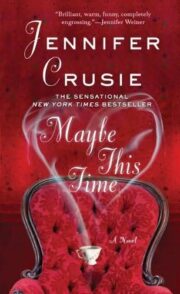

"Maybe This Time" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Maybe This Time". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Maybe This Time" друзьям в соцсетях.