'Do you really mean that?'

'With all my heart – don't you know I am all yours?'

He kissed her, a long, passionate kiss, then muttered rapidly: 'One day, I shall remind you of those words. When I need you I will tell you as frankly as today I tell you that I love you. But just at present, what I need is your love, your being here, your wonderful voice – and your body, of which I can never tire. Sleep now – but not too deeply. I shall wake you when I come back—'

Later, Marianne would often look back on those days at the Trianon. It was broken by the meals taken helter-skelter in the pretty room looking out over the bare, winter woods, by the long excursions on foot or on horseback in the course of which Marianne had been able to note that Napoleon was nowhere near as good a rider as herself, by long fireside talks and by the sudden bursts of passion which hurled them into one another's arms at the most unexpected moments and then left them panting and exhausted, like ship-wrecked mariners washed up on some strange shore.

During the hours Napoleon devoted to his exhausting work, Marianne also worked. On the second day, the Emperor had taken her into the music room and reminded her that before very long she would have to face the public in Paris. She had flung herself into her work with a new ardour, perhaps because she was conscious of him there, close by, and because sometimes he would slip quietly into the room to listen to her for a moment.

It was true, she had to do her studying alone, but she soon discovered in her lover an expert capable of appreciating the most obscure musical points. He was astonishingly versatile. He might have been as good a teacher as Gossec, just as he could have been a talented writer or a remarkable actor. As time went on, the admiration he inspired in his young mistress became stronger than ever. She longed desperately to be worthy of him, one day perhaps to reach those arid, inaccessible regions where he moved.

Yet perhaps conscious of the extent to which his bewitching Marianne had given herself to him, Napoleon gradually began to confide in her a little more. He would talk about certain problems, small ones perhaps, but which gave her an insight into the vastness and complexity of his task.

Each morning, she saw Fouché, her old tormentor now become the most gallant and attentive of her admirers, appear in person to give the Emperor his daily report on all that was going on in his vast Empire. Whether in Bordeaux, in Anvers, in Spain, Italy or the smallest villages of Poland or the Palatinate, the Duke of Otranto's fantastic organization seemed, like some gigantic Hydra, to have an eye hidden everywhere. Let a grenadier be killed in a duel, an English prisoner escape from Auxonne, a ship from America dock in Morlaix with despatches or cargo from the Colonies, a new book appear or a vagabond commit suicide, Napoleon would know it all the next day.

In this way Marianne learned, incidentally, that the chevalier de Bruslart was still at large and the baron de St Hubert had managed to make his way to the island of Hoedic, where he had boarded an English cutter, but she felt no great interest in the news. The only thing she wished to talk about was the one subject that no-one mentioned in her presence, that of the future Empress.

There seemed to be a conspiracy of silence on the subject of the arch-duchess. And yet, as time passed, her shadow seemed to loom ever larger over Marianne's happiness. The days were so short and passed so swiftly. But every time she tried to bring the conversation round to the arch-duchess, Napoleon side-stepped the issue with depressing skill. She sensed that he did not want to talk about his future wife to her and feared to see, in his silence, a greater interest than he cared to admit. And meanwhile, the hours flew by ever more swiftly, the wonderful hours that she so longed to hold back.

However, on the fifth day of her stay at the Trianon, something occurred which came as an unpleasant shock to Marianne and very nearly spoiled the end of her stay.

Their walk that day had been a short one. Marianne and the Emperor had intended originally to go as far as the village where Marie-Antoinette had once played at being a shepherdess, but a sudden fall of snow had forced them to turn back half-way. Soon the flakes were falling so thick and fast that in no time at all they were up to their ankles.

'Wet feet,' Napoleon said with finality, 'are the worst thing possible for the voice. You can visit the Queen's village another day. But instead – ' a gleam of mischief danced in his eyes, ' – instead, I'll promise you a first-rate snowball fight tomorrow!'

'A snowball fight?'

'Don't tell me you never played at snowballs? Or doesn't it snow in England nowadays?'

Marianne laughed. 'Indeed it does! And snowballs might be thought a proper pastime for ordinary mortals – but for an emperor…'

'I have not always been an emperor, carissima mia, and my earliest battles were fought with snowballs. I got through a prodigious number of them when I was at college in Brienne. I'm a devil of a hand, you wait and see!'

Then he had slipped his arm about her waist and half-leading, half-carrying her, had set off at a gallop back to the rose-coloured palace where the lamps were already bright against the darkening sky. There, since the time set aside for 'recreation' was not yet over, the two of them had retired to the music room, where Constant brought them an English tea with buttered toast and jam which they ate in front of the fire, as Napoleon said, 'like an old married couple'. Afterwards, he asked Marianne to sit at the great gilded harp and play to him.

Napoleon was passionately fond of music. It calmed and soothed him and in his frequent periods of abstraction he liked to have it as a murmurous background to lend wings to his thoughts. Besides, the sight of Marianne seated behind the graceful instrument, her slender white arms etched against the strings, was to him an exquisite enchantment. And today, in a gown of watered silk the same green as her eyes that rippled to the light with every inclination of her body, her dark curls clustered high on her head and bound with narrow ribbons of the same subtle shade, pearl drops in her ears and more pearls, round and milky, like a huge cabochon between her breasts and joining the high waist, she was irresistible. She knew it, too, for while her hands played without effort the slight air by Cherubini, she could see dawning in her lover's eyes a look which she had learned to know. In a little while, when the last, vibrating notes had died away, he would rise without a word and take her hand to lead her to their room. A little while – and once more she would know those moments of blinding joy which only he could give her. But meanwhile the present, filled with sweet anticipation, had its own charm.

Unfortunately for Marianne, she was not allowed to enjoy it to the end. Right in the middle of her sonata, there came a timid scratching on the door which opened to make room for the furiously blushing face of a youthful page.

'What is it now?' Napoleon spoke curtly. 'Am I not to have an instant's peace? I thought I said we were not to be disturbed?'

'I – I know, sire,' stammered the wretched boy. It had obviously taken more courage on his part to enter the forbidden room than to storm an enemy redoubt. 'But – there is a courier from Madrid! With urgent despatches!'

'Despatches from Madrid invariably are,' the Emperor commented dryly. 'Oh, very well, let him come in.'

Marianne had ceased playing at the first words and now she rose hurriedly, preparing to withdraw, but Napoleon signed to her briefly to be seated. She obeyed, divining his annoyance at being disturbed and his reluctance to leave his comfortable fireside for the draughty corridors leading to his office.

The page vanished, with significant haste, to return a moment later and throw open the door to allow the entrance of a soldier so liberally plastered with mud and dust that it was impossible to see the colour of his uniform. The soldier advanced to the middle of the room and stood to attention, chin up, heels together, his shako on his arm. Marianne stared thunderstruck at a face fringed with a few days' growth of golden beard, a face she knew from the first moment, even before he fixed his eyes in a blank, military stare on the grey and gold silk covering the wall and spoke.

'Sergeant-major Le Dru, with special despatches from his excellency the Duke of Dalmatia to his majesty the King Emperor. At your majesty's service!'

He it was, the man who had made a woman of her and to whom she owed her first, disagreeable experience of love. He had not changed much in these past two months, despite the ravages of fatigue upon his face, and yet Marianne had the feeling that she was looking at a different man. How, in so short a space of time, had Surcouf's sailor become transformed into this stony-faced soldier, the messenger of a duke? On his green jacket she noted with surprise the brand new mark of the Legion d'Honneur. But Marianne had been long enough in France to realize the kind of magic which surrounded Napoleon. What might have seemed preposterous or absurd elsewhere was the daily bread of this strange country and the giant who ruled it. In no time at all, a ragged sailor out of an English prison hulk could become a hero of the army, galloping like a centaur from one end of Europe to the other.

Napoleon, hands clasped lightly behind his back, walked slowly round the newcomer who, stiff with pride and awe, strove desperately to overcome his weakness under this august scrutiny. Marianne sat wondering how long it would be before Le Dru's glance fell on her and what would happen then. She knew the Breton's impulsive nature too well not to fear the worst. Who could tell how he would react on seeing her? Better to slip away quietly now and disarm Napoleon's probable wrath later.

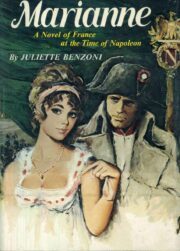

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.