The Emperor's office was a plain room, dominated by tall mahogany book-cases. Marianne remembered the woman waiting there at once. How could she ever forget that dark, fascinating creole face? Fortunée Hamelin's style of beauty was frankly exotic and, at thirty-four, she was still a remarkably attractive woman with magnificent black hair, teeth that were very white and pointed, and red lips with a very slight thickness that betrayed perhaps a touch of negro blood. With all this went an island grace which only Josephine could rival. The one came from Martinique, the other from Saint Domingo but they had always been firm friends. Marianne liked Madame Hamelin's steady, smiling eyes and even the strong scent of roses which enveloped her like a cloud.

As soon as Marianne appeared, looking somewhat stiff and uncomfortable, Fortunée leapt up from the little green and gold striped satin sofa on which she had been sitting amid a great mass of furs, and came forward eagerly to embrace her, exclaiming as she did so in her musical creole voice:

'My dear, dear girl, you cannot conceive how happy it makes me to take you under my wing. For ages I've been longing to steal you from that great stupid princess! How did you manage to dig her out, sire? Our dear Talleyrand watched over her like Jason with the Golden Fleece—'

'To be honest, it was not so very hard. The old rogue was hoist with his own petard! But I shall not prevent you telling him that I have given her into your keeping – on condition he keeps his mouth shut. I don't want her talked of for the moment. He will have to make up some story when he knows what has become of her.' Napoleon smiled wickedly. 'I have an idea,' he went on, 'he must be beginning to feel a little anxious about her! Now, run away both of you. It is nearly time for my levee. Your carriage is at the side gate, Fortunée?'

'Yes, sire. It is waiting.'

'Excellent. I'll come to your house tonight, about eleven. Now be off with you. As for you, my singing bird, take care of yourself but think only of me.'

He was in a hurry now, fiddling nervously with the heaps of papers and portfolios in red morocco which littered his enormous desk. But Marianne herself was too lost in thought to feel offended. Madame Hamelin's reference to the Golden Fleece had reminded her of the companion of her adventures and the recollection was not a pleasant one. He had been hurt, he might be waiting for her and she would have to break the word she had given him. It was an uncomfortable thought. But then, she was so happy. She could not help preferring that slight sense of guilt to the regret that would have been hers had she left France. Jason would soon forget the girl he had won at cards in one night's madness.

Napoleon tweaked her ear. 'You might at least kiss me instead of standing there dreaming,' he reproached her. 'The time will go slowly for me, until tonight. But I must send you away.'

Fortunée had gone discreetly to look out of a window but even so Marianne was conscious of her presence and gave herself to his embrace with some timidity. Napoleon, though still in his dressing-gown, was Emperor once more. She slipped from his arms and swept him a deep curtsey.

'Your majesty's to command and, more than ever, his faithful servant.'

He laughed. 'I love you when you put on your court airs,' he told her. Then, in a different voice, he called out; 'Rustan!'

On the instant, the mameluke appeared, dressed in a splendid costume of red velvet embroidered with gold and a white turban. He was a Georgian of great size, formally sold as a slave by the Turks and brought home by General Bonaparte with a hundred others from his Egyptian campaign. Although he slept each night across the emperor's door, he had been married for two years to the daughter of an usher at the palace, Alexandrine Doubille. No one could have had a more peaceable nature but Rustan, with his brown skin, his turban and his great, curved scimitar, was an impressive figure, although it was his exotic character which most impressed Marianne.

Napoleon now told him to conduct the two ladies to their carriage and, with a final curtsey, Marianne and Fortunée left the imperial presence.

As they went down the little private staircase behind Rustan, Madame Hamelin slipped her arm through her new friend's, enveloping her in the scent of roses.

'I predict that you will be all the rage,' she said gaily, 'that is unless his majesty enjoys playing sultan and keeps you shut up too long. Are you fond of men?'

'I – I am of one man,' Marianne said in astonishment.

Fortunée Hamelin laughed. She had a warm, open, infectious laugh that showed a gleam of sharp, white teeth between her red lips.

'No, no, you don't understand! You do not love a man, you love the Emperor! You might as well say you love the Pantheon or the new triumphal arch at the Carroussel!'

'You think it is the same thing? I don't. He is not so imposing, you know. He is—' She paused, hunting for the word that would best express her happiness but, finding nothing strong enough, she simply sighed: 'He is wonderful!'

'I know that,' the Creole exclaimed. 'And I know too, how attractive he can make himself; when he wishes to take the trouble, that is, because when he cares to be disagreeable—'

'Can he be?' Marianne cried, genuinely astonished.

'You wait until you have heard him tell a woman in the middle of a ball room: "Your dress is dirty! Why do you always wear the same gown? I have seen this one twenty times!" '

'Oh no! It cannot be true!'

'Oh yes, it is, and if you want me to tell you what I really think, it is that which makes his charm. What woman is there who is truly a woman who does not long to know what this boorish Emperor with his eagle look and boyish smile is like in bed? What woman hasn't at some time or other dreamed of playing Omphale to his Hercules?'

'Even – you?' Marianne asked a trifle wickedly. But Fortunée answered with perfect sincerity.

'Yes, I admit it – for a while at least. I got over it very quickly.'

'Why was that?'

Once again that irresistible laugh rang through the palace corridors and out to the steps.

'Because I am too fond of men! And believe me, I have good reason. As for his majesty the Emperor and King, I think that what I have given him is worth as much as love.'

'What is that? Friendship.'

'I wish,' the other woman said in a voice grown suddenly thoughtful, 'I wish I could be really his friend! Besides, he knows I am fond of him – and more than that, that I admire him. Yes,' she added with sudden fervour, 'I admire him more than anyone in the world! I am not sure, if, in my heart of hearts, God does not take second place to him.'

The sun was just rising, painting the Venetian horses on the new triumphal arch a delicate pink. It was going to be a lovely day.

Madame Hamelin lived in the rue de la Tour d'Auvergne, between the former barrière de Porcherons and the new barrière des Martyrs, cut in the wall of the Fermiers Généraux, in a charming house with a courtyard at the front and a garden at the back where, before the Revolution, the Countess de Genlis had brought up the children of the Duke d'Orléans. For neighbour, she had the inspector of the Imperial Hunts and opposite, a dancer from the Opéra, Margueritte Vadé de l'Isle, the mistress of a financier. The house itself had been built in the previous century and recalled the clean lines of the Petit Trianon, although with substantial outbuildings and while the wintry garden was silent and melancholy, there was a fountain singing in a pool in the courtyard. Marianne liked it at once, and especially because the sloping street lay a little out of the common way. Even at this hour of the morning, with servants going to and fro about their work and the cries from the streets as Paris woke once more, there was something quiet and restful about Fortunée's white-walled house which made her feel much happier than all the luxurious splendours of the Hôtel Matignon.

Fortunée conducted her guest to a delightful room done up in pink and white pekin silk with a bedstead of pale wood hung with full white muslin curtains. This room, which was close to her own, belonged to her daughter Léontine, then away boarding at Madame Campan's famous school for girls at St-Germain. And suddenly, Marianne realized that the Creole's vagueness was only apparent and that she was, on the contrary, a person of great energy. In no time at all, Marianne found herself presented in succession with a flowing robe of lace and batiste, a pair of green velvet mules, a lady's maid all to herself (all these being possessions of Léontine Hamelin) and a substantial breakfast. To this last, she was very soon sitting down by a good bright fire in company with her hostess, who had also shed her walking dress. Marianne was amused to see that the former merveilleuse, who had once dared to appear in public in the Champs Elysées stark naked underneath her muslin gown, happily reverted to her old ways in the privacy of her own apartments. Her filmy draperies, in spite of an abundance of delicately coloured ribbons, did little to conceal her perfect figure and served, in fact, to bring out something of the primitive, southern quality of her dark beauty.

The two young women set to with enthusiasm to consume new bread, butter, preserves and fresh fruit, washed down with quantities of tea drunk very hot and strong with milk in the English fashion, all served on an exquisite pink service of exotic pattern. When they had eaten, Fortunée sighed contentedly.

'Now,' she said, 'let us talk. What would you like to do now? Bathe? Sleep? Read? For myself, I mean to write a note to Monsieur de Talleyrand to let him know what has become of you.'

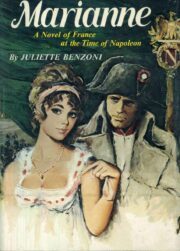

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.