'But – he did not see you?'

Gracchus-Hannibal gave a shrug.

'Who notices an errand boy? Paris is full of us. And we all look much the same. As for the party in the sapin, you can find out for yourself, if you don't believe me.'

'How?'

'Have you other calls to make, or are you going home?'

'Only to "La Reine d'Espagne" and then to the post. After that I am going home.'

'Than you can easily see with your own eyes. And with eyes like yours, you ought to see all right!' Gracchus-Hannibal blushed more furiously than ever. 'I mean to keep with you myself, only, if you wouldn't mind telling me where you live? You see, if it's at Auteuil or Vaugirard—'

Eloquent miming told Marianne that, if that was so, his legs would not stay the course.

'I live at Prince de Talleyrand's in the rue de Varennes—'

'Oh, then I'm not surprised you're being followed! It's all intrigue where the limping devil's concerned! It may be one of Fouché's men. But here—' He looked suddenly anxious, 'you aren't family, are you?'

'Because you spoke of him so? No, don't worry. I am merely reader to the princess.'

'I'm glad, in a way – but then, in another, I don't see why the minister of police should want to know about you?'

Neither did Marianne and this made it all the more necessary to check on the boy's observation for herself. Each morning, reluctantly but without fail she had delivered the previous night's report to the servant, Floquet.

'I'll take your advice,' she said, 'and see if this carriage is really watching me. Whatever the truth, thank you for telling me. Will you come and see me one day?'

'At the prince's house? Not on your life! I'd be lucky if I got as far as the butler in a place like that. But I'll find you, if I need to. Just tell me your name, in case I should have anything to report. I can write, you see,' he added proudly.

'Excellent. I am Mademoiselle Mallerousse.'

There was no mistaking the disappointment on the boy's face.

'Is that all? You've such a look about you, you ought to be called Conde or Montmorency at the least! But there, one doesn't choose one's name. Goodday to you mam'zelle!'

Gracchus-Hannibal settled his blue cap firmly on his head, tucked his umbrella underneath his arm and strolled off whistling with his hands in his pockets, leaving Marianne feeling slightly dazed at what she had just heard. As she walked slowly back to her own carriage, she glanced at that standing outside La Petite Jeannette. The man inside could not have seen her talking in the shadow of the doorway. He must think she had forgotten something and gone back inside. Climbing into the carriage as though nothing had happened, she called out to Lambert, the coachman, while Fanny was busy wrapping a fur rug round her knee: 'Now to "La Reine d'Espagne"—'

'Very good, mademoiselle.'

The smart brougham drawn by a fine pair of Irish greys moved off in the direction of the boulevard, passing the stationary vehicle and allowing Marianne a glimpse of a dark figure inside, then turned the corner by the café Dangest and passed under the trees of the boulevard Italienes. Marianne waited a few moments and turn turned round just in time to see the black cab also turn into the boulevard. She turned again as they drew up outside the famous furriers and saw the cab pull in behind a large delivery cart. It was there again at the post office and was still in sight when the brougham finally turned into the rue de Varennes.

I don't like it, Marianne thought while Jorif the porter was opening the gates for the horses. Who are these people, and why are they following me?

She had no means of finding out except the one possible way of mentioning it in her report. If Fouché were responsible, he would not admit it but if the man in the black cab were not one of his he would certainly give her some instructions.

Somewhat comforted by this decision, Marianne jumped down from the carriage and leaving Fanny to take care of her parcel made her way into the great hall and up the marble staircase to render an account of her morning's errands.

She was in a hurry since M. Gossec was due to give her her daily lesson in a few minutes time. These lessons had become the great joy of her life. She felt her own excitement warmed by that of the old teacher and worked hard in the hope of soon earning her freedom.

She had just put her foot on the bottom step when Courtiade, the prince's valet, appeared at her elbow.

'His serene highness awaits mademoiselle in his study,' he said in the measured tones which never varied and were the very essence of the model servant he was.

After almost thirty years in the Prince's service, he had come in some degree to identify himself with his master, even to adopting certain of his more innocent mannerisms. Courtiade's sole function in the household was to wait upon the prince and he was both respected and feared by the other servants, in whose eyes he possessed something of the powers of an eminence grise. Consequently, the pretended Mademoiselle Mallerousse looked at him in some surprise.

'His highness, you mean – the prince.'

'His serene highness,' Courtiade repeated with a bow and that slight pursing of his lips which marked his disapproval of such lack of respect, 'has instructed me to inform mademoiselle that he has been awaiting her return. If mademoiselle will follow me.'

Suppressing a faint expression of annoyance as she thought of her singing lesson, Marianne followed the valet to the door of the room with which she was more familiar than Talleyrand knew.

Courtiade tapped discreetly, entered and announced: 'Mademoiselle Mallerousse, my lord.'

'Let her come in, Courtiade. Then go and inform Madame de Périgord that I shall have the honour to wait on her at five o'clock.'

Talleyrand was seated at his desk but at Marianne's entry he rose and bowed briefly before resuming his seat and motioning his visitor to a chair. He was dressed, as usual, in black, but the star of the order of St George glittering on his breast reminded Marianne that he was to dine that day with the Russian ambassador, the aged Prince Kurakin. On one corner of the desk stood an antique vase of translucent alabaster, filled with exquisite roses of a red so dark as to be almost black but wholly without scent. The only fragrance in the room was a faint smell of verbena which Talleyrand liked. Cheered by a ray of sunshine which took away some of the austerity from the dark curtains, the room breathed an atmosphere of privacy and peace.

Marianne sat on the edge of her chair, hardly daring to breathe for fear of disturbing the silence, broken only by the faint scratching of the prince's pen on the paper. Talleyrand finished his letter, then, throwing down his pen, raised his pale eyes to look at her. There was something cold and enigmatic in his expression which made Marianne uneasy without quite knowing why.

'The Countess de Périgord seems to hold you in great esteem, Mademoiselle Mallerousse. That is no mean achievement, you know. What witchcraft did you employ to gain that victory? Madame de Périgord is too young to give her friendship by halves. Is it – your voice?'

'That may be so, my lord, but I do not think so. It is simply, that I speak German. It is not only the sound of my voice but that of her native town which pleases the countess.'

'I can believe that. You speak several languages, I believe?'

'Four, my lord, not counting French.'

'Indeed! Girls are well taught – in Brittany. I should never have believed it. However, that decides me to ask you whether, in view of your education, you would agree to act as my secretary from time to time. I need someone to translate certain of my letters. You could be very useful to me and the princess would be quite willing to lend you.'

The proposal took Marianne by surprise and she felt the colour flood into her cheeks. What Talleyrand was suggesting to her was quite impossible. If she were to become his secretary Fouché would know of it at once. He would be delighted and instantly demand vastly more detailed and interesting reports. Marianne had absolutely no desire to record anything beyond the society gossips and small, day to day, household items to which she had prudently confined herself so far. Fouché had been satisfied with that and that was how it must go on. But if she were to be admitted to a sight of the prince's correspondence, Fouché would no longer be satisfied with it and then Marianne would be obliged to become the one thing she was determined not to be and believed at present she was not, which was a real spy. She stood up.

'My lord,' she said, 'I am deeply sensible of the honour your serene highness does me, but I cannot accept.'

'And why not, if you please?' Talleyrand said sharply.

'I – I am not a fit person. Your highness is a statesman, a diplomat, I am fresh from the country and in no way fitted for a post of such importance. Even my handwriting—'

'You write an excellent hand, I believe. At least, if this is anything to go by, eh?'

He took some sheets of paper from a drawer as he spoke and, to her horror, Marianne saw that what he held in his hand was the report she had given Floquet that morning. She knew then that she was lost. For an instant, the mahogany furniture seemed to dance before her eyes as though the house itself were falling and she had a momentary impression that the bronze lustre had fallen on her head. But it wasn't in Marianne's nature to go to pieces in a crisis. All her instincts were to stand up and fight. The blood drained from her face with the effort it cost her but she managed to show nothing of the desperate fear which possessed her. With a little curtsey to the prince, she turned on her heel and walked collectedly towards the door.

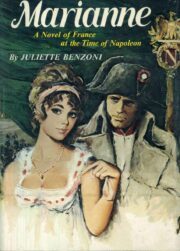

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.