She rose with an effort, yawned and stretched herself. Lord but she was sleepy! It was no good, bed was too tempting. She scowled at the unfinished report. She was much too tired to go on. With sudden decision, she picked up the pen and wrote quickly: 'I am too tired now. I will finish tomorrow.' Quickly sketching the star which was to serve as her signature, she folded the paper and sealed it with wax and a plain seal which she found in one of the drawers, then slipped it under her pillow. After all, she had nothing really exciting to report. She might as well go to bed.

She was just undoing the ribbons which fastened her wrapper when she was arrested by hearing a quite unexpected sound. Cutting through the muted hum of conversation, she had distinctly heard a cry of anger, followed at once by the sound of sobbing.

She listened intently but, although she heard nothing more, she was certain that she had not been dreaming. She went quietly to the window which she had left open, in spite of the weather, for the sake of fresh air. At Selton Hall she had always been used to sleeping with her window open. Now, leaning out, she saw lights in two windows, one of which was directly beneath her own. She knew already that this was the room in which the prince was accustomed to work. There must have been a window open there too because she could now hear the sobs quite clearly. Then came the smooth tones of the prince himself.

'Really, you are being quite unreasonable! Why must you upset yourself like this, eh?'

But almost immediately there came the sound of the window being shut and Marianne heard nothing more. But she could have sworn it was a woman crying, and she sounded desperate. Marianne went slowly back to her bed. Her curiosity was wide awake now but still training held her back. She could not go listening at keyholes, like any servant, or like a spy – which, of course, was precisely what she was. On the other hand, there was the chance of being able to help someone in trouble. The woman who was crying had sounded dreadfully unhappy.

Her curiosity now decently cloaked in human kindness, Marianne quickly exchanged her wrapper for her mulberry coloured dress and slipped out of the room. A small service staircase at the far end of the gallery led directly to the floor below, emerging not far from Talleyrand's office.

As she reached the bottom of the stairs, Marianne saw a long spear of light stretching across the floor, coming from the office door. It must have been left ajar. At the same time, she heard the sobs once again and then a youthful voice with a strong German accent.

'Your behaviour with my mother is abominable, unspeakable. Surely you must understand that I cannot endure the knowledge that she is your mistress?'

'Aren't you a little young to upset yourself about such matters, my dear Dorothée? The affairs of adults are no concern of children and, despite your marriage, you are still a child to me. I am very fond of your mother—'

'Too fond! You are too fond of her and all the world knows it. There are those old women who are forever hanging round you, with their squabbling and tittle-tattling. Now they are trying to make Mama one of them, forcing her to join their little club, what one might call Monsieur de Talleyrand's harem! When I see Mama surrounded by Madame Laval, Madame de Luynes and the Duchess of Fitz James it makes me feel like weeping—'

The young voice rose angrily, reaching a note of shrill, high-pitched fury that was only increased by the imperfect French which made its owner stumble over some of the words.

Marianne knew now who it was in the room with the prince, whose the sobbing and the cries of anger. She had seen her in the salon only a little while before. It was the prince's niece, Madame Edmond de Périgord, formerly Princess Dorothée de Courlande, a young and very wealthy heiress whom Talleyrand had succeeded, with the Tsar's help, in marrying off to his nephew a few months previously. She was very young, sixteen at the most, and Marianne had thought her on the whole rather plain, thin, sallow and gauche, although dressed in a style of elegance that betrayed the hand of Leroy. Her one beauty, but that quite remarkable, was her enormous eyes which seemed to fill the whole of her small face. They were of a strange colour which seemed at first to be black but was in fact dark blue merging into brown. But Marianne had been struck by the little princess's air of breeding and the wilful, slightly arrogant way she had of throwing back her head as children did when they were determined not to show that they were frightened or unhappy. Of the husband, she could recall very little; a personable but undistinguished youth in the splendid uniform of a hussar officer.

Monsieur Fercoc, the tutor, who had chatted to her for a while, had also remarked, in discreetly veiled terms, on the relations existing between Talleyrand and the Duchess of Courlande, Dorothea's mother. He had pointed out the blonde duchess, sitting with three other women; they were no longer young, but their air of assurance, verging on insolence, clearly recalled the old court of Versailles. All three had been Talleyrand's mistresses and remained his most devoted admirers. Their loyalty to him was limitless and very nearly blind.

'The three Fates!' Marianne had thought with the unconscious cruelty of seventeen, ignoring the fact that these women retained the traces of great beauty. However, there were too many people in the room for her to dwell on them for long.

On the other side of the door, Talleyrand was still endeavouring to soothe the angry girl.

'I am surprised at you, Dorothée. I should never have believed you capable of listening to every piece of gossip that circulates in Paris. To most of these busybodies, a friendship between a man and a woman can mean only one thing—'

'Why do you have to lie to me?' the young woman burst out furiously. 'You know quite well it is not gossip but pure truth! Gossip may be all very well but I know, I know I tell you! And I am ashamed, so terribly ashamed when I see two heads getting together behind a fan and eyes looking first at me, and then at my mother! And this is a shame that I will not endure. I am a Courlande!'

The last words rose almost to a scream. Marianne, standing stock-still in the darkened gallery, heard the prince cough dryly but when he spoke again she noticed that his voice had taken on an icy hardness.

'If you are so fond of gossip, my child, you should take more note of the old rumours concerning your forebear, Jean Biren – made Duke of Courlande by the whim of a Tsarina. Was it really true that he was a groom? Certainly, hearing your language tonight, I should be tempted to believe it! You must learn to control yourself, I think. It really will not do to shout in this way in Paris, or indeed in any civilized society. If you are so sensitive to gossip, you should have chosen a convent, my child, rather than marriage—'

'As though I had chosen it!' the girl said bitterly. 'As though you had not forced your nephew on me, knowing I loved another!'

'Another whom you never saw and who thought little enough of you. If Prince Adam Czartoriski had been so anxious to marry you, he might have behaved in a less distant fashion, eh?'

'How you enjoy hurting people! Oh, I hate you!'

'No, you don't. There are times when I think you love me more than you will admit, even to yourself. Do you know, your little outburst smacks a good deal of jealousy? Now, don't get on your high horse again. Calm down, smile and let me tell you something. I know of no one in this world we live in who does not love and respect your mother. She is a woman born to be loved. So, be like everyone else, my child. This world hangs in a very delicate balance. Take care your tantrums do not shake it.'

The sobs had begun again. Marianne listened, unable to tear herself away. She had only just time to spring back into the shadows of the staircase when the door was thrown wide open and the prince's tall figure appeared in the doorway. He stepped outside, seemed to hesitate for a moment then shrugged and moved away. The regular click of his stick and the more irregular sound of his footsteps on the tiled floor quickly died away. But, inside the room, Dorothée de Périgord was still crying.

Again, Marianne hesitated. What she had overheard was a private matter which did not concern her but she felt drawn to the little sad-eyed princess and wished she could help her. Surely, it was quite natural for the child to feel revulsion at the spectacle of a liaison between her mother and her uncle by marriage? Such adventures might be all very well for the fashionable world but no truly pure and principled mind could fail to be hurt by them.

Marianne sighed and turned regretfully to make her way upstairs. She felt very close to the girl weeping in there. Dorothée was suffering from an unhappy love, as she herself had suffered, but there seemed nothing she could do for her. Better to go back to her room and try to forget, for not for anything in the world would Marianne have reported what she had just heard to Fouché. She was just turning away when, through the now closed door, she heard the girl speak again.

'I loathe this hateful country! There is no one who understands me! No one! If there were just one person—'

This time, she spoke in German and with such a mixture of rage and pain in her voice that Marianne could no longer resist the urge to fly to her assistance. Before she realized what she was doing, she had pushed open the door and walked in. It was a large room, rather plainly furnished in mahogany with dark green hangings. Dorothée was walking agitatedly up and down, her arms folded and her cheeks streaked with tears she had not bothered to wipe away. She stood facing Marianne who murmured in a soft voice:

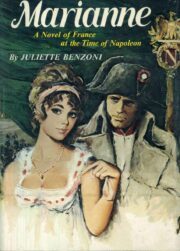

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.