'We've sailed right into a storm—' Marianne shrieked breathlessly.

'This? A storm?' Black Fish laughed. 'You wait till you see a real storm, lass. You won't forget it. This is just a nice little slice of wind to see us on our way, strong enough to make the coastguards think twice about sticking to our heels. And don't come telling me you're frightened. I warned you.'

'I am not frightened!' Marianne declared fiercely. 'And to prove it, I shall sleep here!'

'You'd be better in the cabin.'

'No!'

The real reason was that she could not bring herself to go down there. In the cabin was the unknown man, the escaped prisoner who must be some kind of desperado since he was one of Napoleon's fearful Frenchmen. Marianne was a hundred times readier to face the battering of the wind and even the occasional dollop of sea water than the company of a man whose very presence on board only made her the more conscious of the evils of her own situation. The only distance now between the escaped prisoner and the erstwhile mistress of Selton Hall was in Marianne's own will. And yet, now that she had nothing to do but wait for the approach of the French coast, her accumulated weariness overcame her. She was so tired she could have gone to sleep lying in a puddle. Besides, the unaccustomed heavy fumes of the rum were beginning to make themselves felt.

'As you like,' Black Fish said. 'You can wrap this round you.'

It was a length of sail cloth, coarse to the touch but dry and thick enough to be almost waterproof. Marianne folded it round her gratefully, making a kind of cocoon with herself inside. Then, curled into a ball like a cat in a basket with her head on a coil of rope, she closed her eyes and fell instantly asleep.

The face which Marianne beheld when she opened her eyes was a pleasant one. Clean manly features framed in a short golden beard and grey eyes, at present filled with admiration. For a moment, she thought it must be a continuation of her dream which had transported her temporarily back to Selton which still seemed so close. But the world to which the face belonged was a long way from the quiet English countryside. It was a turbulent, watery world of grey skies with heavy clouds racing as far as the eye could see, of salt spray and icy waves rising and falling in a froth of boiling foam. Towering above this world of water was the massive figure of Black Fish standing at the Seagull's wheel, great hands clamped to the spokes, as huge and outlandish as some sea god from a nightmare.

The man with the fair beard put out a hand and touched Marianne's damp cheek with one finger.

'A woman!' he murmured, as if unable to believe his eyes. 'A real woman! Do they still exist?'

Black Fish's thunderous laugh rose above the roar of the wind.

'They surely do, and a darned sight more of them than is any good for the peace of honest lads like you and me! Take no notice of her, lad.'

'She is pretty, though—'

'She's well enough, but what her lay is, I don't know. Told me some yarn about wanting to go to France to find some boy, but that's a lie, I know. If she's not scared to death, then I'll be hanged. She's scared and running from something, maybe the law – likely she's a thief. With her pretty face, she's prigged some swell cove's dibs, I shouldn't wonder, and now they're after her—'

Throughout this dialogue which took place in French, Marianne had managed to keep silent but to hear herself accused of theft was more than she could bear. Pushing aside the canvas, she burst out fiercely in the same language:

'I am not a thief and I forbid you to insult me! I did not pay you for that!'

Both men gaped at her in surprise and Black Fish almost let go of the helm.

'How's this, you speak French?'

'Why not?' she said haughtily, 'Is there a law against it?'

'No – but you might have said!'

'I do not see why! You did not tell me that you speak it – like a native!'

'That's enough sauce from you, my girl,' Black Fish growled. 'I'd talk a bit less flash, if I were you. There's nothing to stop me taking you by the scruff and pitching you overboard. You seem a funny kind o'mort to me. Whose to say you ain't a spy?'

Marianne was too angry to be frightened.

'No one,' she retorted. 'And if you wish to throw me in the sea, feel free to do so! You will be doing me a service. I regret only that I was mistaken in you. I took you for a smuggler. It seems, however, that you are a murderer!'

'Hell and damnation—'

Black Fish, red with anger, had dropped the helm and was about to throw himself at the girl. At the strong risk of being hurled overboard himself, the fugitive from the hulks cast himself bodily between them and thrust back the giant who stood uncertainly, his fist still raised.

'Nicolas, are you out of your mind? Behave yourself. Can't you see she's only a kid?' Turning to Marianne, he asked her kindly: 'How old are you, little one?'

'Seventeen,' she said reluctantly. Then added almost at once: 'Why do you call him Nicolas?'

The young man began to laugh, showing firm strong teeth.

'Because it's his name. You don't think he was christened Black Fish? And you, what are you called?'

'Marianne—'

'A pretty name,' he said with approval, 'but Marianne what?'

'Marianne nothing! Is it any of your concern? I have not asked you questions!'

He drew himself up and made a ceremonious bow, rendered absurd by the enormous garment Black Fish had found for him to wear.

'I am Jean Le Dru, native of Saint Malo—' he paused and added with a simple pride which did not escape Marianne, ' – and I sail with Surcouf!'

Had he been a king's son, he could not have said it with more pride. Marianne did not know who Surcouf was but, feeling suddenly drawn to him in spite of herself, she smiled and said: 'I had thought you to be one of the Corsican's men.'

He stiffened, frowned imperceptibly and looked at the young woman with narrowed eyes.

'Surcouf serves him and I serve Surcouf. And let me add that when we speak of him, we say the Emperor!'

He turned without further comment and went to seat himself beside the Black Fish. Realizing that she must have wounded him in his convictions, Marianne inwardly cursed herself for a fool. There had been no need for her to show her dislike of the man he spoke of with such ceremony as the Emperor. He was a Frenchman and she in his power for, to her great surprise, Black Fish had not reacted as a loyal Englishman should have done. Throughout the brief contretemps, he had not stirred, content with staring vaguely out to sea. She wondered if Black Fish were really English. The way he spoke French gave some room for doubt.

Left to herself, Marianne tried to retreat once more into her shell of damp canvas and go to sleep but this proved impossible. The vessel was pitching badly in the choppy seas of the Channel and Marianne became suddenly very much aware of the movement. Beyond the rail, the grey waves fell into deep hollows as though the sea would open up beneath the ship, then swelled up again, driven by the wind. The horizon had disappeared. Now there was no land in sight, not even a rock, only the sea birds and the universal grey waters through which the sloop plunged blindly on, her sails strained to breaking point.

Marianne was suddenly overcome by an appalling feeling of nausea. She closed her eyes and let herself go. It seemed to her that she was dying. That everything was falling to pieces around her and her stomach responded to every lurch of the vessel. Never having been sea sick before, she did not know what was happening to her. She tried to stand up, clinging to the rails, but once again the sickness overpowered her and she sank back utterly exhausted on to the deck.

The next thing she felt was two hands holding her and someone lifting her up. Something cold was pressed against her mouth.

'Feeling bad, eh?' the voice of Jean Le Dru said in her ear. 'Drink this, it will do you good.'

She recognized the strong, pungent smell of rum and swallowed some mechanically. But her empty stomach rebelled against the spirit. Abruptly thrusting aside the arm which held her, she opened wide terrified eyes and made for the ship's side with a strangled yell.

For the next few dreadful minutes, Marianne forgot all dignity in the spasmodic heaving of her stomach. She did not even mind the sea which slapped her face wetly, although this helped to revive her. She clung to the rail while Jean, his arm clamped securely round her waist, did his best to stop her falling overboard. When the violent retching subsided a little at last, she sagged like an old pillowcase and would have fallen if the Breton had not caught her. Gently, with almost motherly care, he laid her back on the canvas and covered her as best he could. Black Fish's voice came to her, as though through cotton wool.

'Shouldn't have made her drink. Probably hungry.' 'That's the best bout of seasickness I ever saw,' the other answered. 'I'd be surprised if she could swallow a mouthful—'

But Marianne was past joining in the argument. She was conscious of nothing but the moment's respite granted her by this sudden frightful illness and, hardly daring to breathe, was watching for the smallest sign on the part of her body. The lull was in any case only a short one, for after a few minutes the retching began again and Marianne was once more a prey to seasickness.

With the fall of night, the gale became a tempest and curiously Marianne's sickness grew less. The pitching of the vessel became so violent that it put an end to the nauseating lurching of her stomach. She emerged at last from the depths of misery in which that hellish day had passed but only to meet another kind of horror, this time fear.

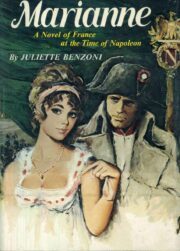

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.