'It may not matter to you but you forget the hounds of Bonaparte. In France, Madame, I am a proscribed émigré. Merely to approach my country is to risk my head. But if it is your desire to go there, you may easily find some fisherman who deals in contraband, here in this very town, who for a consideration will certainly put you ashore somewhere on the coast of Normandy or Brittany.'

Marianne gave a little shrug.

'What could I do in France? I have no family there any more. But then, nor have I anywhere.'

A sardonic gleam came into the gentleman's red-rimmed eyes. He gave a dry cackle of laughter.

'No family? Oh but you have. I know of two persons at least connected to you by blood.'

'Two? How can this be? No one has ever spoken of them to me.'

'They are little enough to boast of. I should think Lady Selton preferred to forget that part of the family but the fact remains that you have two cousins, one closer than the other, to be sure, but the second a person of some standing!'

'Who are they? Tell me quickly,' Marianne said eagerly, her dislike of the old duke momentarily forgotten.

'Ah, you would like to know. It does not surprise me and, from what I have just learned of you, you should deal very well with both these ladies. One is a poor demented creature, your poor father's cousin. Her name is Adelaide d'Asselnat. She never married and long ago severed all connections with her family on account of her disgraceful opinions. La Fayette, Bailly and Mirabeau were among her friends and there was always a welcome at her house in the Marais for all those wretches responsible for overthrowing the throne of France. She must, I believe, have gone into hiding during the Terror to have escaped the guillotine which devoured the first masters of the revolution as well as its nobler victims. But I presume she must have reappeared and should not be surprised to learn that she had become transformed into one of Bonaparte's most loyal subjects. As for the other – she stands even closer to the Corsican ogre.'

'Who is she?'

'Why, his own wife. Citizeness Bonaparte, whom they call the Empress Josephine nowadays, has for her maternal grandmother a Mary Katherine Brown of the Irish family. She was the daughter of a Selton and married Joseph-François des Vergers de Sanois. Her daughter, Rose-Claire, married Tascher de la Pagerie, whence Josephine.' The duke gave a twisted smile. 'Family history holds no secrets from us,' he added sardonically. 'We have time enough in our exile.'

Marianne was a prey to a host of contradictory feelings. The knowledge of her close connection with the wife of Napoleon gave her no pleasure, quite the contrary, for throughout her childhood she had been used to hearing her Aunt Ellis alternately abusing and deriding the man she never referred to as anything but 'Boney'. Lady Selton had taught her to hate and fear the Corsican oppressor who had dared set himself up on the throne of the martyred king, to blockade England and crush all Europe under his heel. To Marianne, Napoleon was a monster, a tyrant spawned by the hideous revolution which, like a vampire, had sucked the finest blood of France including that of her own parents. She left d'Avaray in no doubt as to her sentiments.

'I have no call to seek help from Madame Bonaparte – but I should be glad to see my cousin d'Asselnat.'

'I am not sure I approve your choice. The Creole is well connected. She has even a few drops of Capet blood in her veins, a little secret unknown to her husband and which may yet cost him dear. While the demoiselle d'Asselnat is only a foolish old woman whose sympathies are scarcely more creditable. Now, permit me to take leave of you. I have matters to attend to.'

Marianne too had risen. Standing, she was a head taller than the duke. She looked down at the sick man whose shoulders were once more in a terrible spasm of coughing.

'For the last time, my lord Duke, will you not take me?'

'No. I have told you my reasons. Permit me to die with nothing with which to reproach myself. Your servant, madame.'

He bowed, so slightly as to make the courtesy an insult. Marianne coloured angrily.

'Wait one moment, if you please!'

Taking from her bosom the locket presented to her the day before, she flung it furiously onto the table.

'Take this back, my lord! Since I am no longer one of you, I have no claim to it! Remember, I am English now and a criminal to boot.'

For a moment, the duke looked at the jewel gleaming on the soiled cloth. He put out his hand to take it, then changed his mind. He looked up and regarded Marianne with mingled pride and anger.

'It pleased her Highness to make this gift in recognition of your mother's sacrifice. To return it would be to offend her. You had better keep it. After all,' he went on with a chilly smile, 'you are at liberty to throw it in the sea if you do not want it. It might even be better so. As for you, may God help you for you will escape neither His anger nor your punishment, not if you flee to the ends of the earth!'

He moved away leaving Marianne angry and mortified as well as bitterly disappointed. Everything she trusted, everything she believed in seemed fated to crumble to dust in her hands. Never she swore, would she forget this humiliation. But, for the present, some other means must be found.

By evening Marianne was once again on the old Barbican. She had sold her horse for a good price and further exchanged her riding clothes for a good plain dress of brown wool and a thick cloak with a deep hood worn over a white linen mob cap, and a pair of stout shoes and coarse woollen stockings. She had never worn such garments before but she felt comfortable in them and very much safer. Her money and the pearls were stowed away in a strong canvas pocket sewn into her petticoat. Dressed like this, she was no longer an object of curiosity and would be able to roam the Plymouth waterfront very much as she liked. Her next task was to find a vessel that would carry her to France. In this, time was against her and every hour that passed increased the danger of discovery and arrest.

Unfortunately, knowing no one in the town made it hard to know whom to approach especially in so delicate a matter as a clandestine passage. For a long time, Marianne walked up and down the quay, watching the comings and goings of sailors and fishermen all around her, often tempted but never quite daring to approach them. She wandered on in no particular direction, oblivious of the cheerful bustle of the harbour. As evening drew on, the wind sharpened. Soon she would have to find an inn to spend the night, somewhere more modest than the Crown and Anchor, but she could not yet bring herself to do so. Tired as she was, she could not help feeling somewhat nervous at the prospect of being shut up for the night between four walls and was besides quite sure she would not be able to sleep.

As she passed Charles II's fort, one of the sentries called after her. With a nervous shiver, she hurried on, hugging her cloak more closely about her. The man laughed and uttered some coarse pleasantry but made no attempt to come after her. She saw the old Smeaton fire tower a little way ahead, its bright light a nightly warning of the dangerous approaches to the great port. Bleak and lonely on its rock, rising above the sand, the beacon with the great iron cage that held the light and its supporting masts looked like nothing so much as a great ball of wool stuck on to knitting needles. The flag hung like a wet sheet from the upper platform, so sodden with rain that the wind barely stirred it. There seemed to be no one about and this loneliness, with the moaning of the wind, gave the place a somewhat sinister aspect. Marianne almost turned back but then she saw an old man sitting on a rock right beneath the grey tower and smoking his pipe. Timidly, she went up to him.

'If you please—' she began.

The old man cocked a bushy eyebrow under the faded red stocking cap, revealing a wickedly bright eye.

'What are you doing out here, at this time of night, my pretty, eh? The sailors from the fort have an eye for a pretty girl and the wind's getting up. Likely it'll blow your bonnet over the windmill!'

There is often a secret, unspoken sympathy between the very old and the very young. The old man's friendly tone gave Marianne confidence.

'I know no one in this town, and I must find someone to ask. I thought that, perhaps you might—'

She did not finish. The old man's eyes had quickened and he was studying her with the keen glance of a seaman, accustomed to noting the minutest variation of sea or sky.

'You are no country maid, though you may dress like one. Your voice gives you away. No matter, my girl. What do you want to know?'

In a low voice, as though ashamed of what she had to say, Marianne told him:

'I must find a vessel to take me across the sea – and I cannot tell who to approach.'

'Why, the Harbour Master, of course! It all depends on where you want to go—'

'To France.'

The old man gave a low whistle which vanished on the wind.

'That's another matter entirely, but even there, the port office may be able to do something for you. You must not think our brave English lads are frightened of Boney and his war dogs. There are still some who run the blockade.'

'But I cannot go to the port office,' Marianne broke in impatiently. 'I have no papers. I – I have run away from my parent's house and I have to get to France.'

The old man thought he understood. He chuckled loudly, winking and nudging her with his elbow.

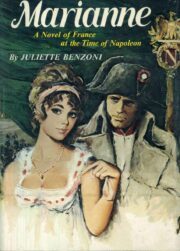

"Marianne" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne" друзьям в соцсетях.