Even as she was about to plunge over the side, she was caught and held roughly by an irresistible force. Arms were round her body and she found herself held fast, in total impotence, against the broad chest of the fisherman, Jacopo.

'Tut, tut!' said Giuseppe's voice softly. 'How very childish! Does your ladyship seek to leave us? Where would you go? There is nothing here but grass and sand and water… whereas a luxurious palace awaits you…'

'Let me go!' she moaned, struggling with all her strength, her jaws grimly clenched to keep her teeth from chattering. 'Why should you care? You can say I hurled myself into the water – that I am dead! Only let me off this boat! I'll give you anything you want! I am rich—'

'But not so rich as his highness… and much less powerful. My life is a poor thing, Excellenza, but important to me. I do not want to lose it. And I am bound to answer with my life for your ladyship's safe arrival!'

'This is absurd! We are not living in the Middle Ages!'

'Here, in certain houses, we are,' Giuseppe said, suddenly grave. 'I know, your ladyship is going to mention the Emperor Napoleon. I was warned of that. But this is Venice, and the Emperor's power is exercised lightly and with discretion. So, be sensible…'

Marianne was sobbing now, still held fast in Jacopo's arms, her spirit broken and her resistance at an end. She was not even conscious of the absurdity of crying in the arms of a perfect stranger: she merely leaned against him as she might have done a wall, with one thought only in her mind: everything was finished. Now nothing could prevent the Prince from wreaking what vengeance he liked on her. She had only herself to rely on, and that was little enough.

Yet at the same time, she was aware of something odd happening. Jacopo's arms were little by little tightening round her and his breath was growing shorter. The young man's body, pressed against her, was beginning to tremble. She felt one hand move surreptitiously upwards from her waist, seeking the curve of her breast…

Suddenly it was borne in on her that the fisherman was trying to take advantage of the situation, while Giuseppe had moved a yard or two away and was waiting, with an air of boredom, for her to dry her tears.

The fisherman's caress acted on her like a tonic, restoring her courage. If this man's desire for her was strong enough to make him take such an insane risk right underneath Giuseppe's nose, then he might be prepared to take still more risks for the promise of another reward.

Therefore, instead of slapping Jacopo's face, as she would have liked to do, she pressed herself more closely against him. Then, making sure that Giuseppe was not looking, reached up on tiptoe and brushed the boy's lips swiftly with her own. It was only an instant, then she pushed him away, at the same time gazing into his eyes with an expression of earnest entreaty.

As she moved away he watched her with a kind of desperation, evidently struggling to understand what it was she wanted of him, but Marianne had no means of expressing her wish. How could she convey to him by gestures that she wanted him to knock Giuseppe down and tie him up securely, when Giuseppe was at that moment moving towards them? A hundred times in the course of the last twenty-four hours she had hoped to find some implement on the boat which might have enabled her to do the thing herself. After that, to reduce Jacopo to a state of total obedience would no doubt have been child's play. But the servant was no fool and took care of himself. Nothing was left lying about on board that might have served as a weapon, and he scarcely ever let Marianne out of his sight. He had not closed his eyes all night.

Now was there anything within reach that could be used to write with? It was not even possible to scratch a message to the fisherman on the side of the boat, asking for help. Besides, he probably could not read.

Daylight faded and still Marianne had found no way of communicating with her unusual admirer. For an hour or more, Giuseppe sat on a heap of ropes between the two of them, turning his pistol round and round in his hands, as though he guessed the threat which hung over him. Any attempt would certainly have proved fatal to both.

With a sinking heart, Marianne watched as the anchor was hauled up and the tartane slipped out into the channel in the dusk. In spite of the terror which gripped her, she could not help a gasp of wonder, for the skyline had been transformed into a fantastic fresco of blue and violet colours, intermingled with lingering traces of red gold. It was like a fantastically ornamented crown lying on the sea, but a crown already fading into the dark.

Night fell quickly and by the time the tartane had rounded the Isola di San Giorgio and entered the Canale della Giudecca the darkness was almost complete. She sailed close-reefed, feeling her way, seeking perhaps to attract as little attention as possible. Marianne held her breath. She felt Venice closing round her like a clenching hand, and gazed with painful longing at the tall ships which, once past the white columns and gilded Fortune of the Dogana di Mare, rode sleepily with riding lights aglow, off the airy domes and alabaster volutes of la Salute, awaiting for tomorrows of salt winds to carry them far from this perilous siren of water and stones.

The little vessel tied up away from the quay, beside a group of fishing boats, and when Giuseppe momentarily turned his back at last to lean over the side, Marianne seized the opportunity to move quickly to where Jacopo was furling the sails and lay her hand on his arm. He trembled and looked at her then, dropping the sails, made as if to draw her to him.

She shook her head gently and with a fierce movement of her arm towards Giuseppe's back, endeavoured to make him understand that she wanted to be rid of him… at once!

She saw Jacopo stiffen and glance first at the man whom he no doubt considered his master, then at the woman tempting him. He hesitated, clearly torn between conscience and desire… His hesitation lasted a moment too long, for already Giuseppe had turned and was making his way back to Marianne.

'If your ladyship pleases,' he murmured, 'the gondola waits and we should not delay.'

There were two more heads visible now over the side of the boat. The gondola must be close alongside the tartane and it was too late: Giuseppe had allies.

With a scornful shrug, Marianne turned her back on the young sailor. She had completely lost interest in him now, although a moment before she had been ready to give herself to him as the price of her freedom, with no more hesitation than St Mary the Egyptian to the boatmen she had need of.

A slim black gondola lay waiting alongside. Escorted by Giuseppe, and without a single backward glance at the tartane, Marianne took her place in the felze, a kind of curtained black box in which the passengers sat on something like a low, broad sofa. Then, sped by long oars, the gondola slid over the black waters. It nosed its way into a narrow canal beside the church of la Salute, whose golden cross still watched silently over the health of Venice as it had done ever since the great plague in the seventeenth century.

Giuseppe bent forward as though to draw the black leather curtain.

'What are you afraid of?' Marianne asked with contempt. 'I do not know this city and no one here knows me. Let me look, at least!'

Giuseppe hesitated for a moment before sighing resignedly and resuming his seat beside her, leaving the curtains as they were.

The gondola turned into the Grand Canal and now Marianne saw that the splendid ghost was indeed a living city. Lights shone in palace windows, driving back the darkness here and there and making the water sparkle with reflections of spangled gold. Sounds of voices and music floated out of open windows, filling the soft May night. A tall gothic palace was ashimmer with light, and a waltz tune sounded above a garden which dripped luxuriant greenery into the canal. A cluster of moored gondolas danced to the rhythm of the violins below the steps of a noble stair which seemed to rise from the very depths of the waves.

Huddlled in her dark retreat, Giuseppe's prisoner saw women in brilliant gowns and well-dressed men mingling with uniforms of every colour, the white of Austria prominent among them. She could almost smell the scents and hear the bursts of laughter. A party!… Life, joy… Then, suddenly, all was gone again and there was only the darkness and a vaguely musty smell. The gondola had turned aside abruptly into a little cut walled in by blind house walls.

As in a bad dream, Marianne glimpsed barred windows, emblazoned doorways, and now and then walls with crumbling plasterwork, as well as graceful arched bridges under which the gondola glided like a ghost.

At last they came to a small landing-stage below a red wall topped with black ivy, in which was the ornately carved lintel of a little stone doorway framed by a pair of barbaric wrought-iron lanterns.

The fragile craft came to a halt and Marianne knew that this time it was really the end of the journey, and her heart missed a beat. She had come again to the house of the Prince Sant'Anna.

But on this occasion no servant waited on the green-stained steps leading down to the water, or in the slip of a garden where plants sprang thickly round the ancient carved-stone well, as though out of the very stones. Nor was there anyone on the handsome stairway which led up to the slender pillars of a gothic gallery, at the back of which the red and blue glass of a lighted window shone like jewels. But for that light, the palace might have been deserted.

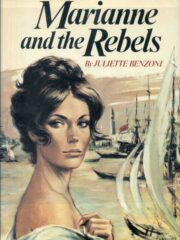

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.