In turn, they swarmed noiselessly up the ladder and dropped on to the empty deck. Marianne's heart was thudding so that she could hardly breathe. Everything looked just the same, and yet somehow different. The deck had lost its impeccable whiteness. Odd things seemed to be lying about there; the brass was dull and sheets hung loose, swaying slightly in the night wind. Then there was the silence…

She could not explain the apparently deserted condition of the vessel. Someone must surely come… a seaman… the lieutenant, Craig O'Flaherty… or perhaps her old friend Arcadius, whom she missed in his absence almost as much as Jason himself. But no. There was no one. Nothing but that glimmer of light forward. It was towards this that Theodoros was now moving cautiously, one step at a time, only to draw back swiftly into the shelter of the mainmast as two men, carrying long-muzzled guns, came out of the forecastle hatch. Marianne and her companion knew at once what they were, from their red and blue garments, their tall felt hats with the spoon for rice stuck in it, their gleaming weapons and the warlike air. They were janissaries.

'They are guarding the ship,' whispered Theodoros. 'That means there is no crew on board.'

'Maybe, but that isn't to say the captain isn't here either. Let me go and look.'

Unable to endure the uncertainty a moment longer, gripped by a fear she could not have described, and by the same sense of something amiss which had struck Theodores earlier, she glided like a shadow past the deckhouse, its door swinging crazily off its hinges, and reached the poop and climbed up, taking care to avoid the faint beam from the single stern light.

Eagerly she sprang towards the door that led into the after-cabin and the captain's own sleeping cabin, but there she pulled up short, staring in bewilderment at the boarded-up doorway and, on the planks nailed across it, the great seals of red wax, like drops of blood.

Only then did she look around her, taking in the details she had missed before but which now stood out clearly in the dim light. Everywhere there were traces of a fight: in the splinters of wood torn from the rails and spars, the twisted metalwork and the marks gouged in the deck by cannon shot, and most of all in the dark stains which were most sinisterly evident around the wheel.

At that moment hope abandoned her.

There was nothing more to wait for, nothing to look for, either. Jason's beautiful ship was now a ghost-ship, the battered remnant of the thing she had once been. Someone, certainly, had recaptured her from the mutineers, but whoever that someone was, it was not Jason, could not be, or why these signs of battle? Why the seals? A Barbary pirate, perhaps, or perhaps some Ottoman rais had come upon the Sea Witch far from land, half out of control in the inexperienced hands of Leighton and his crew, and she had fallen an easy prey.

To Marianne's distraught mind, it seemed all too clear what must have happened, from the grim traces left on board. Everything proclaimed a battle lost, defeat and death, even down to the bored soldiers keeping guard over the floating wraith, since, for good or ill, it was now obviously the property of some noble person.

As for those she loved and had last seen here, where no echo of their voices now remained, she would never see them more. She knew that now, for certain. They were dead.

Utterly broken by this latest blow, Marianne slid to the deck, oblivious of everything around her, and with her head against the boarded-up door that Jason would never use again, gave herself up to silent tears. It was there that Theodoros found her, huddled against the wood as though trying to become a part of it.

He tried to make her stand but could not, for all his great strength. She had become a dead weight, loaded down with an immense burden of misery and despair which were beyond him, as a man, to cope with. She simply lay there, crushed to the ground by the rocklike pressure of grief and disappointment, and he knew that she would make no attempt to drag herself out of it. For her the outside world had simply ceased to matter.

Theodoros knelt beside her and, feeling for her hand, found it cold as if all the blood had already drained away from it. Yet the hand moved, pushing him away.

'Leave me alone…' she whispered. 'Go away!'

'No. I'm not leaving you. You are grieving, therefore you are my sister. Come.'

She was not listening. He guessed that she had wandered away from him again, borne on the bitter stream of her own tears, far beyond all reason and logic. Cautiously he raised his head and looked about him.

The janissaries were away up in the bows of the ship and had heard and seen nothing. They were sitting on coils of rope, their guns between their knees, and had taken out long pipes and were smoking placidly, gazing out at the night. The rich scent of tobacco mingled with the smell of seaweed on the breath of the breeze that wafted to them from the Black Sea. Obviously, neither of them suspected there was any other creature on board but their two selves.

Slightly reassured, Theodoros bent over Marianne once more.

'Please, you must try! You cannot stay here… it is madness! You must live, you must go on fighting!'

He was using his own terms to persuade her, the things that made up all the world for him. She did not even answer but only shook her head, almost imperceptibly, and he could feel her tears wet on his hand. He was overwhelmed with compassion such as he had never felt before.

He knew that this woman was brave and eager for life, and yet the words of life and battle had no power over her now.

She lay there, as a dog will lie outside the door of its dead master, and he knew that she would never move again unless he did something. All she wanted was simply to lie where she was until death took her. Yet she was so young… so beautiful.

He was seized with anger against all those who had tried to make use of that youth and beauty, so ill-protected by the resounding titles which did not compensate for the load of responsibility they had burdened her with, himself among the rest. He was ashamed of himself, remembering the oath he had wrenched from the castaway before the sacred icons. Not everything was justified in the cause of freedom. And now that she could no longer help herself, this over-tried child who, for all that, had done her best to help him, had even killed for him, he was not going to abandon her.

She had not moved for some time, but when he tried again to lift her, he felt the same refusal, the same resistance which told him that if he persisted she was capable of screaming aloud. Yet they could not stay where they were for ever. It was too dangerous.

'I'm going to make you live in spite of yourself,' he muttered through his teeth, 'but for what I am about to do, forgive me!'

He raised his huge hand. He had learned much about all forms of fighting and he knew how to knock a man out with a single, scientifically-delivered blow to the back of the head. Judging the power of his arm to a hair's breadth, he struck. There was no more resistance. The girl's body slumped instantly and relaxed. Immediately, he slung her across his shoulder and, bending double so as to be indistinguishable from the bulwark, he made his way back to the entry port where the companion ladder hung.

It was no effort at all. His burden was as nothing to the joy of getting her away.

Seconds later, he had taken the sculls and was steering the perama towards the harbour entrance. A few minutes more and he would have reached the place that he had selected and could carry his companion to the French embassy, which he knew well. Only then would he be able to return to his own battle and to the terrible sufferings of his country. But first he had to return this child to her own place and her own people. She was like a delicate flower that cannot live in strange soil but can only find the nourishment it needs to live and grow in its own ground.

The boat rounded Galata point, past the walls of the old castle, and the minarets belonging to the mosque Kilij Ali lifted their vague white columns to the star-filled sky. They were out on the choppy little waves of the Bosphorus now, and the boat began to dance a little.

Theodoros, still pulling at the oars, began to smile suddenly. Though the wind was cold, the night was clear, calm and beautiful.

It was not a night for tragedy. There was some mistake somewhere. What it was he could not tell, but his instinct, the instinct of a man brought up among mountains and used from boyhood to looking at the sky and the stars, told him now that for the woman lying unconscious in the bottom of the boat, the sunshine and the happiness were not gone for good, and Theodoras' instinct had never betrayed him yet. The longest road winds to an end at last, and the longest night must pass and see the dawn.

For the Emperor's envoy, this voyage at least was done and the time come to set foot on the soil of the Grand Signior and the fair-haired Sultana.

With a decisive gesture, Theodoras the rebel sent his boat into the calm waters of a little bay and drove it hard up against the sandy shore.

The Comte de Latour-Maubourg, French ambassador to the Sublime Porte, stared with stupefaction at the scarecrow figure of the giant who had invaded his embassy and dragged him from his bed by thundering on his door, bellowing like a bull, and then pushing his way past the porter.

Next, his perplexed and myopic gaze went to the young woman whom the intruder had deposited, quite unconscious, in a chair, as tenderly as if he had been her mother.

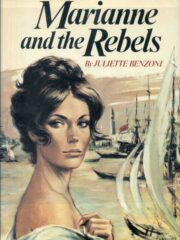

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.