Decked out in a full white gown with triple, floating sleeves, a sleeveless and collarless coat embroidered in red wool, a pair of silver buckled shoes, and even a big red velvet cap, Marianne presided that very evening over Sir James's dinner table, her exotic apparel forming an interesting contrast to the officers' blue uniforms and the plain evening dress of the other two gentlemen.

She provided the only faintly discordant note in what was otherwise a typically English evening. Everything about Sir James's cabin was firmly and unalterably English, from the table silver and the Wedgwood china to the heavy, old-fashioned furniture, the pervading aroma of spirits and cigars – and the lamentably insular cooking.

In spite of the variety of strange dishes she had eaten in the course of her improbable odyssey, Marianne discovered that her stay in France had profoundly altered her taste in culinary matters. She scarcely recognized the dishes she had enjoyed as a child.

Afterwards there were toasts to the King, to the Royal Navy, to Science and to 'Miss Selton', who then made a most affecting little speech, thanking her rescuer and all those who were taking such good care of her.

The two architects were literally drinking in her words, unmistakably impressed by her natural elegance and grace. Both succumbed instantly to her charm – as did all the men present – but each reacted somewhat differently. Whereas Charles Cockerell, a sanguine, rather over-fed young man with an air of regarding life as one enormous Christmas pudding, gazed at her hungrily and lost himself in compliments that tended towards a vaguely Thucydidean turn of phrase, his friend Foster, who proved to be a thin, nervous person whose reddish hair, cut rather long, gave him a disconcerting look of a red setter, said little except in monosyllables, darting quick glances at her out of the corner of his eye. But what little he did say was addressed solely to her, as if none of the others present existed.

After dealing for a while in a general way with the rumblings of revolt that were beginning to be heard in the islands, the conversation soon settled down to a discussion of the exploits of the two colleagues at Aegina and at Phygalia. At this point, the two of them entered frankly into competition with each other, each shamelessly doing his best to claim the greater part of glory for himself at the expense of the other. The only thing in which they were united was their joint criticism of Lord Elgin who, they said, 'had only to bend down to pick up a fortune' with the admirable metopes from the Parthenon.

'At the rate we're going,' Sir James said gloomily as he escorted his guest back to her cabin, 'those two will have come to blows before the voyage ends. Ah, well, I suppose I can always hand them over to the master at arms to ensure fair play. But for goodness' sake, my dear, take care not to smile at one more than the other, or I won't answer for the consequences.'

Marianne laughed and promised, but as time went by she was forced to admit that this lighthearted promise was harder to keep than she had anticipated. For in the few days it took for the Jason to reach the Dardanelles, the clash of rivals continued. She could not set foot on deck for a breath of air without one or other, if not both, rushing to keep her company. She began to think they must be mounting guard outside her door. In addition, she soon found their company wearisome in the extreme, since their style of conversation was identical and in both cases revolved around their own magnificent discoveries which they were burning to exploit.

There was another passenger who was sorely tried by the two architects. This was Theodoros. He thought them utterly ridiculous, with their straw hats, their flowing neckcloths, close-fitting white clothes and the green sunshades with which they persisted in shielding their pallid northern complexions – and in the case of Foster, his freckles – from the sun's rays.

'You'll never be able to get rid of them when we get to Constantinople,' he told Marianne one evening. 'They follow you like shadows and they won't give up when we go ashore. How will you manage? Will you take them with you, as escort, to the French embassy?'

'It won't be necessary. They are only interested in me because they are bored and have nothing else to do on board ship. That, and a certain snobbishness. Once we land, they'll be too busy to think of me. All they want is to get their horrid permit and scurry back to Greece.'

'What sort of permit?'

'Oh, I don't know. They've found a ruined temple and they want permission to dig about for buried stones and things. They want to make drawings, too, and study classical architecture – all that sort of thing.'

The Greek's face had hardened.

'There was an Englishman came to Greece once before. He had been ambassador in Constantinople, and he had permission to do all those things. But he wanted more than just to find things and make drawings. He wanted to take the stones with carvings on them away to his own country – stealing the ancient gods of my land. And he did it. Whole cargoes of stone sailed from Piraeus, taken from the temple of Athena. But the first, and most important, never arrived. A curse was on it and it sank. These men long to do the same. I can feel it. I know.'

'Well, we can't stop them, Theodoros,' Marianne said gently, laying a soothing hand on her odd companion's muscular arm, as knotted as an olive trunk. 'Your mission, and mine, are each more important than a few stones. We cannot risk failure, especially as we don't really know. Besides, their ship may sink, too!'

'You are right, but you will not stop me hating these vultures who come to snatch away what little glory my poor people have left.'

Marianne was deeply struck by the bitterness of this man whom she now looked on as her friend, but she had imagined the incident closed and forgotten when events proved her dramatically wrong.

The Jason had entered the narrow straits of the Dardanelles and was sailing past the desolate expanse of black earth and sandy waste, with bare hills topped by bleached ruins and the occasional tiny mosque, round which the snowy seabirds wheeled incessantly.

In this corridor of brassy blue, like a broad lazy river, the heat was intense, flung back from bank to bank of treeless, petrified land. In this incandescent universe, the smallest movement became an effort that set the sweat pouring. Marianne lay on her cot, with nothing on but a single shift that clung to her skin, gasping for air despite the open window in the vessel's stern, and taking care not to move. Only her hand waved a fan of woven reed gently to and fro in an attempt to cool an air that seemed to have been breathed straight from a furnace.

It was too tiring even to think, and only one conscious idea floated on the sluggish surface of her mind. Tomorrow they would be in Constantinople. She would not think beyond that. Now was the time to rest, and the ship sailed on in the silence of eternity.

This beautiful silence was shattered abruptly by an angry voice shouting not many feet away. The voice came from the quarterdeck and it belonged to Theodoras. Marianne could not understand what he was saying because he was speaking Greek, but there was no doubt about the fury of his tone. When it seemed to her that the oddly muffled voice answering him was that of Charles Cockerell, Marianne sprang to her feet on the instant, under the remarkably bracing effect of pure terror. She flung on a dress and, without stopping even to put on her sandals, fled out of the cabin. She was just in time to see a pair of seamen literally climbing up Theodoras in their endeavours to prize his fingers loose from the architect's throat.

Horrified, she ran towards them but, before she could reach the Greek, more seamen had come up, in charge of an officer, and Theodoras was borne down by sheer weight of numbers and forced to release his grip. His victim staggered to his feet, gasping and retching, and lurched to the rail, tearing at his neckcloth in his efforts to regain the use of his lungs.

In spite of all that Marianne could do to help, it was a moment or two before he was able to speak. In the meanwhile Theodoras had been overpowered and Sir James had arrived on the scene from his own cabin.

'Good God, Theodoras! What have you done?' Marianne wailed, slapping Cockerell's cheeks to bring him to himself more quickly.

'Justice! I was doing justice! The man is a brigand – a thief!' the Greek said sulkily.

'You don't mean you were trying to kill him?'

'Yes, I do say so! And I'll say it again. He deserves to die. Let him look to himself in future, for I shall not abandon my revenge.'

'You may be in no position to do anything else,' Sir James broke in in a voice of ice. His upright figure inserted itself between the horrified girl and the agitated little group who were finding it increasingly difficult to hold the infuriated Greek. 'I'll have that man in irons, if you please, Mr Jones. He'll be required to answer to a court for his attempt upon Mr Cockerell.'

Marianne's horror became blind panic. If Sir James were to apply the rigid laws of the service to Theodoros, the Greek rebel's career bade fair to finish at the end of a yard or under the lash of the cat-o'-nine tails. She flew to his assistance.

'For pity's sake, Captain, at least hear what he has to say. I know this man. He is good and true and fair! He would not have done this without a good reason. He is not English, remember, but Greek, and he's my servant. I am the only person to answer for him and for his conduct. I am quite willing to do so.'

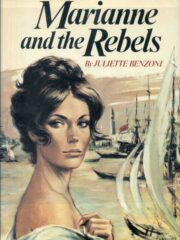

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.