'Thank you. That's better.'

'You frightened me,' he said after a moment, with a sigh of relief. 'I couldn't think what was the matter. You slept well enough. I know because I've been in several times.'

'I can't think what came over me. I was having weird dreams and then when I woke up I started thinking – oh, of things that are lost to me.'

'You were dreaming of this ship. I heard you – you spoke the name.'

'No, not the ship… a man of the same name.'

'A man you – love?'

'Yes, and shall never see again.'

'Why? He is dead?'

'Perhaps. I do not know.'

'Then why do you say you'll never see him again? The future is in God's hand and until you have seen your lover's body in the grave you cannot say that he is dead. How like a woman to waste energy on tears and regrets while we are still in danger! Have you thought yet what you are going to say to the captain?'

'Yes. I shall say I'm going to Constantinople to visit a distant relative. He knows I have no near relations left. He will believe me.'

'Then hurry up and get your story straight, because he's coming to call on you in an hour. The man in white told me that. And he gave me these things for you to try and dress yourself. They have no proper women's clothes on board. I'm to bring food for you.'

'I won't have you going to all this trouble on my account. A man like you!'

A swift smile illuminated his craggy face for an instant.

'I am your devoted servant, Princess. I must play my part. These people seem to think it only natural. Besides, you must be hungry.'

In fact, the mere mention of food had been enough to remind Marianne that she was dreadfully hungry. She ate everything that was brought to her, then had a wash and arranged the piece of silk, which Sir James must have bought to take home, in the manner of a classical robe. After this she felt better.

It was a much more self-possessed Marianne who waited for Sir James to make his promised visit and, when he was seated on the only chair, thanked him for his hospitality and for taking such good care of her.

'Now that you are rested,' he said, 'won't you tell me, at least, where I am to take you? As I told you, our course is for Constantinople but—'

'Constantinople will suit me perfectly, Sir James. That is where I was going when – when I was wrecked. I took ship, oh, it seems a very long time ago now, to visit a member of my father's family there. He was French, as you know, and when I fled from England I went to France to try and trace any relatives who might still be living there. There were none, except for one elderly cousin not in very good odour with the present regime. She told me that there was another distant relative of ours living at Constantinople who would certainly be glad to see me, and that after all, travel broadened the mind. So I went, but on account of the wreck I was obliged to spend several months on the island of Naxos. That was where I found my servant, Theodoros. He rescued me from drowning and looked after me like a mother. Unfortunately, the pirates came…'

Sir James's whiskers twitched in a smile.

'He is certainly devoted to you. It was lucky for you that you had him with you. Very well, then. I'll take you to Constantinople. If the wind holds, we'll be there in five or six days from now. But I'll make a landfall at Lesbos and see if I can get hold of some clothes for you. You can hardly go ashore dressed as you are. Very pretty, I grant, but just a trifle improper. Although, of course, this is the east…'

He was talking volubly now, made easier by Marianne's half-confidences, and enjoying both the brief excursion into the past and the prospect of a few days' voyage in her company to revive, for both of them, a nostalgic vision of the green lawns of Devonshire.

Marianne was content to listen to him. She was still a little shaken to discover how easily the lies had come to her – and been accepted. She had mingled truth and fiction with a readiness that left her both startled and alarmed. The words had simply come of their own accord. She was even beginning to find that, with practice, she was actually enjoying the part she had to play, even though there was no audience but herself to applaud her performance. Most of all, it was necessary to act naturally, that most difficult of all arts, because failure would be met not with hoots and cat-calls, but with prison or even death. Even in the awareness of her danger there was something exciting that gave a fresh spice to life and made her understand a little of what it was that gave a man like Theodoros his power.

True, he was fighting for his country's independence, but he also loved danger for its own sake and would seek it out for the sheer exuberant delight of meeting it and beating it on its own terms. Even without the call to liberty, he would have flung himself into perilous adventures for nothing, for the pure joy of it.

She even discovered suddenly that there was another side to her mission, apart from the harsh aspect of duty and constraint, a thrill which, only an hour ago, she would have rejected fiercely. Perhaps it was because it had already cost her so much that she could not bear not to finish it.

She learned from Sir James's rambling monologue that the man in the white suit was called Charles Cockerell and that he was a young architect from London with a passion for antiquities. He had come aboard the Jason at Athens with a companion, another architect from Liverpool, whose name was John Foster. The two of them were on their way to Constantinople to obtain permission from the Ottoman government to dig for relics of classical antiquity on the site of a temple which they claimed to have discovered, since the pasha of Athens, for some obscure reason of his own, had refused them his consent. Both men were members of the English Society of the Dilettanti and had already been exercising their talents on the island of Aegina.

'As far as I'm concerned,' Sir James confessed, 'I'd rather they'd chosen to travel on any other ship but mine. They're not an easy pair to get on with, and mighty full of themselves in a way that could cause trouble with the Porte. But after all the fuss that was made over those marbles that Lord Elgin carried back to London from the great temple in Athens, there's no holding them! They're sure that they can do as well, or better! As a result, they keep on pestering our ambassador in Constantinople with letters complaining that the Turks won't cooperate and the Greeks are apathetic. If I hadn't agreed to give them a passage, I think they'd have stormed the ship.'

Marianne's interest in the ship's other passengers was perfunctory. She had no wish to have anything to do with them and said as much to the captain.

'It would be best, I think, that I should not leave my cabin,' she said. 'For one thing, it's not easy to know what name you should call me. I'm no longer Miss d'Asselnat and I've no intention of using Francis Cranmere's name.'

'Why not call yourself Miss Selton? You are the last of the line and you've every right to use the name. But, surely you must have had a passport to leave France?'

Marianne could have bitten out her tongue. It was the obvious question and she was beginning to find out that the pleasures of lying had their drawbacks.

'I lost everything in the wreck,' she said at last, 'including my passport… Besides, that was in my maiden name, of course, but to use a French name on an English ship…'

Sir James had risen and was patting her shoulder in a fatherly way.

'Of course, of course. But our troubles with Bonaparte have nothing to say to old friendship. You shall be Marianne Selton, then, because you're going to have to show yourself, I fear. Those fellows are as inquisitive as a waggon-load of monkeys, and with an imagination to match! They were very much struck by your romantic arrival and are quite capable of dreaming up some fanciful tale of brigands and God knows what that might well get me into hot water with their lordships at the Admiralty. All ways round, it'll probably be best for both of us if you become thoroughly English again.'

'Do you think they'll believe it? An Englishwoman roaming the Greek islands with a servant like Theodoros?'

'Absolutely,' Sir James laughed. 'Eccentricity isn't a sin with us, you know. More a mark of distinction. Those two scholars are solid citizens enough – and you're Quality. That makes all the difference. You'll have them eating out of your hand. You've excited them enough already.'

Then, in that case, I'll have to satisfy the curiosity of these architects of yours, Sir James,' she said, with a little, resigned smile. 'I owe you that, at least. I should be miserable if you had to suffer, all through saving me.'

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Night on the Golden Horn

It was a quarter of an hour later that the three-decker dropped anchor off the little port of Gavrion on the island of Andros, and a boat was sent ashore carrying Charles Cockerell, whose knowledge of Greek made him the natural person to undertake the mission of trust which he had, in any case, virtually begged the captain to give him.

He might be an impossible person but he was certainly a man of .some resource, for he returned an hour later bringing with him an assortment of female garments which, considering their entirely local origin, were both picturesque and becoming. Marianne, who was beginning to grow accustomed to the fashions of the islands, was delighted with her new wardrobe. Particularly since the gallant architect had thoughtfully included a variety of silver and coral ornaments which did credit both to his own good taste and to the skill of the local craftsmen.

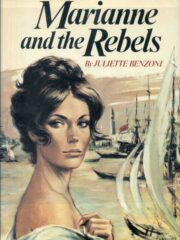

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.