He showed no sign of being disturbed by Kouloughis' tumultuous entry with his captive, but merely raised his exquisitely plucked eyebrows and favoured the girl with a glance that was half-affronted, half made up of sheer distaste. No doubt he would have looked much the same had Kouloughis suddenly thrown a bucketful of slops into his well-ordered world: a new and startling experience for one of the prettiest women in Europe.

The big cabin was well lighted by clusters of perfumed candles. Kouloughis dragged Marianne over to one of these and with a quick movement ripped off the embroidered shawl that covered her head and shaded her eyes. The light shone on the gleaming black mass of her plaited hair, and her green eyes sparkled angrily. She shrank back instinctively from the renegade's hand.

'How dare you! What are you doing!'

'Taking a good look at the goods I propose to sell, that's what I'm doing. There's no gainsaying you've a lovely face and your eyes are very fine – but it's hard to tell what may lie under the clothes worn by the women of my country. Open your mouth!'

'What—!'

'I said open your mouth. I want to see your teeth.'

Before Marianne could stop him, he had gripped her face between his hands and forced her jaws apart with a deftness born of long practice. Marianne might rage as she liked at finding herself treated precisely like a horse; she was compelled to endure the mortifying examination which, it seemed, was entirely to the satisfaction of the examiner. But when Kouloughis tried to undo her dress, she sprang away and fled for refuge behind the table in the centre of the cabin.

'Oh, no, you don't!'

The renegade looked vaguely surprised but he only gave a small shrug of annoyance and called:

'Stephanos!'

This was obviously the name of the dainty occupant of the bunk and, no less evidently, Kouloughis was summoning him to help.

Apparently the youth disliked the idea, because he began to shriek alarmingly and wriggled himself further down among his cushions as though defying his master to dislodge him, giving vent to a stream of words, uttered in a shrill tone that grated on Marianne's ears like a rasp, the gist of which was unmistakable: the delicate creature was refusing to sully his hands with anything so repulsive as a woman.

Marianne, who reciprocated his dislike to the full, had a momentary hope that his refusal might earn him a box on the ears, but Kouloughis merely shrugged and smiled, an indulgent smile that sat ill on his face. Then he turned back to Marianne.

Her attention deflected by the little scene, she was not expecting this new attack, but he made no further attempt to open her dress, being content merely to run his hands swiftly over her body, lingering a little over the breasts and acknowledging their firmness with a satisfied grunt. This treatment was not at all to Marianne's liking and she responded by dealing the slave-driver two resounding slaps.

For a brief instant, she tasted the fierce joy of triumph. Kouloughis stood stock still, rubbing his cheek mechanically, while his little friend seemed ready to faint with shock and indignation. But it was only for an instant. A second later, she saw that she would have to pay dearly for her gesture.

The corsair's sallow face seemed to turn dark green before her eyes. The fact that he had suffered this humiliation before the eyes of his minion made him wild with rage and, staring with dilated eyes, he suddenly seemed to her a creature less than human.

Urged on by the boy, who was now screaming excitedly in the nasal whine of a maniac muezzin, Kouloughis seized hold of Marianne and dragged her bodily out of the cabin.

'You'll pay for that, daughter of a bitch!' he snarled. 'I'll show you who's master!'

'He's going to beat me,' was Marianne's terror-stricken thought as she was jerked towards one of the carronade's that formed the polacca's armament, 'or worse!'

In a trice she found herself bound to the breech. Two men had covered it first with a tarpaulin but not, it was soon clear, with any idea of sparing her unpleasant contact with the metal.

'The meltemi is coming,' Kouloughis told her. We'll have a storm and you shall remain out here on deck until it's over. That may cool your temper. When you're cut loose, you'll have thought better of trying to strike Nicolaos Kouloughis. You'll go down on your knees and lick his boots to spare you further tortures! If you're still conscious!'

It was a fact that an ominous swell was getting up and the ship was beginning to roll. Marianne could feel a queasiness inside that intimated sickness to come, but she forced herself not to blench. She was not going to show this brute that she was ill. He would only think she was afraid. Because of this, she chose to attack instead.

'You're a fool, Nicolaos Kouloughis. You don't know your own interests.'

'My interest is to avenge an insult dealt me in front of one of my men!'

'That? A man? Don't make me laugh! But that's beside the point. You're going to lose a lot of money.'

In no circumstances could anyone utter the word money in Nicolaos Kouloughis's presence without arousing his interest.

'What do you mean?' he said, automatically, disregarding both the fact that only a few moments before he had been on the verge of strangling this woman and the undoubted absurdity of entering into this kind of argument with a prisoner lashed to the breech of a gun.

'It's perfectly simple. You said, didn't you, that you were going to hand Theodoros over to the pasha of Candia and sell me in Tunis?'

'I did.'

'That's why I tell you you are going to lose a lot of money. Do you think the pasha of Candia will pay you as much as the prisoner's worth? He'll try and bargain with you, give you something on account and tell you he needs time to get the rest together… whereas the Sultan will pay much more, and on the spot, in good solid gold! For me too. If you won't believe who I really am, or listen to reason, you will at least admit I'm worth more than the grubby harem of some Tunisian bey! There isn't a woman in the Grand Signior's harem to match me for beauty,' she declared brazenly.

Her plan was a straightforward one. If she could once get him to alter course for the Bosphorus, instead of taking her off to Africa where she would be lost beyond recall, and the very thought of which appalled her, she knew that this in itself would be something of a victory. The important thing, as she had decided once already in Yorgo's boat, was to get there, no matter how.

She studied the corsair's crafty face anxiously to gauge the effect of her words. She knew that she had touched him on the raw, and very nearly breathed a sigh of relief when he muttered at last:

'You may be right…' But in a moment the meditative tone had changed to one of anger and resentment. 'But you've deserved your punishment!' he cried. 'And you shall suffer it none the less. When the storm is over you shall know what I have decided – perhaps!

He went away forward, leaving Marianne alone on the empty deck. Was he going to alter course? Marianne had the feeling suddenly that something was wrong. She had seen how Jason's men had acted during the storm the Sea Witch had run into after leaving Venice, and it bore no resemblance to the behaviour of Kouloughis' crew.

The seamen on the brig had taken in all sail, leaving the yards bare of everything but the jib and staysail. The men on the polacca were gathered in the bows in what appeared to be some kind of conference, broken now and then by the roars of their captain. Some, the bravest probably, began taking in the more accessible canvas, without enthusiasm, glancing uneasily at the topsails to see how they were standing up to the weather. No one showed the slightest inclination to brave the perils of the shrouds that were now swinging and lashing with the pitching of the ship.

Marianne, for her part, was feeling increasingly unwell. The ship was tossing now like a cork in boiling water and the ropes binding her were beginning to bite into her flesh. She gasped as a wave broke right over her and ran away, foaming, into the scuppers.

All the same, when Kouloughis staggered past her on his way aft, she could not resist jibing at him:

'A fine lot of seamen you've got! If this is how they behave in a storm…'

'They put their trust in God and the saints,' the corsair flung back at her. 'The storm is from heaven; it is for heaven to decide the outcome. All Greeks know that.'

This talk of God was the last thing that might have been expected from a renegade pirate, but Marianne was beginning to form her own idea of the Greeks. They were a strange people, at the same time brave and superstitious, ruthless and generous, and for the most part hopelessly illogical. Consequently she merely raised her eyebrows a little and observed:

'I imagine that is why the Turks find them so easy to defeat. Their method is rather different – but I daresay you must know that, from having decided to serve them.'

'I know. That's why I am going to take the helm, even if it does no good.'

Marianne was prevented from answering this as another dollop of salt water slapped over her, sweeping the deck from end to end. She was choking for breath, coughing and spluttering to free her lungs. When she could see anything again, she caught sight of Kouloughis gripping the wheel with both hands and glaring wildly at the raging sea. The helmsman was crouched under the lee of a bulwark, clutching his beads.

Daylight had crept up slowly, a grey daylight that revealed a gloomy sea. Like a wanton woman doing penance, it had put off its blue satins for grey rags. The waves were mountainous and the air full of flying spume. For all Kouloughis' efforts at the wheel, the vessel was driving forward blindly on a course known only to herself and perhaps to the Devil, however illogically the pirates might persist in seeing the hand of God in it.

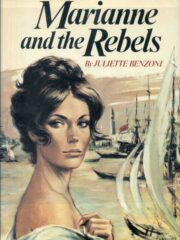

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.