She ran her slender fingers caressingly over the warm stone, as though it could bring her some comfort. It must have seen so much, this old house with its austere device proclaiming the acceptance of suffering. How many times must the setting sun, going down flaming into a sea splashed all over with its golden spume, have shone on this same window; on what faces, what smiles and what tears? The solitude about her was peopled suddenly with faceless shadows, with insubstantial forms wreathing in the amber dust raised by the evening breeze, as though to comfort her. The departed voices of all the women who had lived, loved and suffered between those venerable walls whose glory had now crumbled into ashes whispered to her that this was not the end, here in an ancient palace perched like a melancholy heron on the rim of an island, a palace which had wakened for a moment but would soon fall back into the nothingness of sleep.

For her there were days yet to come when Love might have its say.

'Love? Who was the first to call it Love? Better to have named it Agony…'

Marianne remembered hearing those lines somewhere once and they had made her smile. That was a long time ago, in the first flush of her seventeen years, when she had thought herself in love with Francis Cranmere. Whose were they? Her memory, usually so reliable, failed that night to give her the answer, but it was someone who knew…

'If your highness would be good enough to step downstairs, his lordship will do himself the honour of dining with you.'

Athanasius had not spoken loudly but Marianne started as though at the sound of the Last Trump. Brought abruptly back to earth, she smiled at him vaguely.

'I'll come… I'll come at once.'

She left the room, while Athanasius remained to close the window and shut out demoralizing fantasies behind thick wooden shutters. He caught up with her at the head of the stairs, when her hand was already poised on the white marble balusters polished by years of contact with innumerable human hands.

'If I may warn your highness, do not be surprised at anything you may see or hear during dinner,' he murmured. 'The Count is very old and it is long now since anyone came here. He is sensible of the honour done him tonight but – but he lives with his memories. He has done so for so long now that – that they are to some extent a part of himself. They are with him always. Your highness may have noticed his use of the plural form… I don't know if I make myself clar…'

'You need not worry, Athanasius,' Marianne said gently. 'Nowadays I am not easily surprised.'

'But your highness is so young—'

'Young? Yes… perhaps. But older than I look, I daresay. Don't worry. I shan't hurt your old master – or drive away his familiar spirits.'

Yet, for all that, the meal left her with a curious feeling of unreality. This was due not so much to the old-fashioned suit of green satin which her host had donned in her honour, and which he must have worn long before at the doge's court in Venice, as to the fact that he spoke hardly a word to her.

He greeted her gravely at the door of a large room where suits of rusty armour stood guard round the walls beneath the flaking frescoes, and led her down the whole length of an endless table set with old silver, to a seat placed on the right hand of the chair of state at its head, where he took his own place.

Another place was set at the foot of the table, before a chair identical to that of the master of the house. Only there a half-opened fan of painted silk and mother of pearl lay on the plate of old blue Rhodian ware, and beside it a rose in a crystal vase.

Throughout the meal, it was to the invisible mistress of the house rather than to his youthful neighbour that the old gentleman addressed his remarks. Occasionally he would turn to Marianne, exerting himself to conduct the conversation as if it were actually being directed and initiated by the ghostly countess, and he gave to it a turn of delicate and outmoded gallantry that brought tears to his young guest's eyes. She was overcome with emotion at the sight of a love so faithful that it could transcend the grave and recreate the loved one's presence with this touching persistence.

She learned that the countess's name was Fiorenza, and so strong was her husband's evocation of her presence that he almost made it seem an objective reality. Twice Marianne thought she saw the silken fan quiver delicately.

Now and then she let her eyes wander past the crested back of her host's chair to meet those of Athanasius, standing there in his everyday black suit with the addition of a pair of white gloves. She was not much surprised to note that they seemed abnormally bright.

The food was good and plentiful but in spite of the appalling hunger that was always with her these days, reminding her very much of Adelaide's, Marianne could not do justice to the meal. She nibbled a little, forcing herself to maintain her part in the ghostly conversation and uttering anguished mental prayer that it would soon be over.

When the Count rose at last and, bowing, offered her his arm, it was all she could do not to sigh aloud with relief. She allowed him to lead her back to the door, suppressing a crazy urge to break into a run, and even went so far as to smile and curtsey to the empty chair.

Athanasius followed three paces behind them, bearing a torch.

At the door, she begged the Count not to accompany her further, insisting that she had no wish to disturb his evening, and it wrung her heart to see how he brightened and hurried back into the dining-room. As the door shut behind him, she turned to the steward who was looking at her absently.

'You did right to warn me, Athanasius. It's frightening! Poor man!'

'Your highness must not pity him. He is happy so. For many, many evenings, now, he will talk of your highness's visit, with the Countess Fiorenza. To him, she is still living. He sees her come and go, take her seat facing him at table and sometimes, in the winter, he will play for her on the harpsichord that he had brought here once, at great expense, from a town called Ratisbon in Germany, for she loved music.'

'Was it long ago she died?'

'Oh, she is not dead, or if she is now, we shall never know. She left here, twenty years ago, with the Ottoman governor of the island, who had seduced her. If she still lives, it must be in a harem somewhere…'

'She ran away with a Turk?' Marianne gasped with amazement. 'Was she mad? Your master seems such a good man, so gentle… and he must have been quite handsome at that time…'

Athanasius made a little movement of his shoulders which precisely expressed his opinion of the logic of the female mind, and confined himself to a vaguely apologetic statement which excused nothing:

'Mad, no. She was only a pretty, feather-headed woman for whom life here was not very amusing.'

'I daresay she must have found it infinitely more amusing in a harem,' Marianne said with sarcasm.

'Bah! The Turks are not such fools. There are plenty of women who were made for that kind of life. And there are others who cannot bear to be put on a pedestal. It makes them lonely and afraid. Our countess belonged to both kinds at once. She adored luxury and idleness and sweetmeats, and thought her husband a poor kind of man because he loved her too much. It was after she left that something went wrong with him. He's never accepted the fact that she's gone away, and he has gone on living with the memory of her as if nothing had happened. And what with wanting so much to see her, I think in the end he really came to it, and now he's reached a kind of happiness that's greater, maybe, than he would have had if she'd stayed with him, because the years have not changed the thing he loves… But I'm boring you. Your highness must wish to retire.'

'You aren't boring me, and I'm not tired. Only a little upset. Tell me, where is Theodoras? I haven't seen him.'

'At my house. Since he can't tear himself away from the harbour, I thought best to send him there. My mother will look after him. But if you require his services…'

'No, thank you,' Marianne said, smiling. 'I think I can manage without the services of Theodoros. Let us go up, if you please.'

The first thing she noticed on entering her bedchamber was a small tray placed near her bed, on which was bread and cheese and fruit.

'I thought,' said Athanasius, 'that madame might not have much appetite for dinner, but that perhaps a little something during the night…?'

This time Marianne went straight up to him and, taking his plump hand in both of hers, shook it warmly.

'Athanasius,' she said, 'if you weren't about the only thing your master has left to him, I'd ask you to come with me. A man-servant like you is a gift from heaven!'

'I love my master, that is all… I am sure your highness has the capacity to arouse a devotion as great, or greater than mine. May I wish your highness a good night – and no regrets.'

The night might well have proved every bit as good as the worthy man had hoped, if only it had been allowed to run its proper course. But Marianne was still in her first sleep when she was shaken vigorously awake by a rough hand on her shoulder.

'Hurry! Get up!' said Theodoros' hurried voice. 'The ship is here!'

Marianne peered through half-open eyes at the big man's face, tense in the wavering light of a candle.

'What?' she asked, sleepily.

'You must get up, I tell you. The ship is here and waiting! Get up!'

By way of extra encouragement to her to hurry out of bed, he laid hold of the covers and flung them back, discovering what had evidently been the last thing he had thought of in his haste: a female form clad only in a tumbled mass of dark hair and touched to warm gold by the candlelight. He stood literally rooted to the spot while Marianne, wide awake now, flung herself on the sheet with a howl of rage.

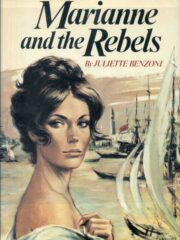

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.