The odabassy showed no disposition to persist. His sneer was transformed into a smile and he bowed to his Empress's cousin as agreeably as he knew how, before departing with his troop.

The rebel, Theodoros, had remained standing rigidly, three steps behind his supposed mistress, while all this perilous explanation was going on. In all that time, he had not flinched, but judging from the long breath he let out as they turned back to the staircase at last, Marianne guessed that he had suffered a nasty moment, and smiled to herself, thinking that, for all his great size, the mighty warrior was only human after all and subject to the same anxieties as ordinary men.

The room to which the old Count led Marianne could not have been in use since the days of the last dukes of Naxos. A bed that could have sheltered an entire family behind its curtains of faded brocade reigned in splendid isolation between four walls proudly adorned with tattered and rust-spotted banners, while a selection of broken stools huddled together in the corners of the room. But there was a magnificent mullioned window with a view of the sea.

'We were not prepared for such an honour,' the old Count was saying apologetically. 'But your servant shall bring you what you need and we will send to the Mother Superior of the Ursuline convent for a suitable gown – since our own size is somewhat different…'

The use of the plural form was bizarre but no more so than the rest of the Count's person or his rather toneless voice and Marianne did not dwell on it.

'I should be most grateful for the dress, my lord Count,' she said, smiling, 'but for the rest, I beg you will not put yourself out. I am sure that we shall have no difficulty in finding a ship—'

The old man's curiously vacant gaze seemed to light up at the word.

'The larger vessels do not often call here. We live in a forgotten land, madame, a land passed over by the hubbub and the glory and the recollections of the great ones of the earth. It is enough to keep us alive, fortunately, but you may find that your stay is longer than you imagine. Come with me, my friend.'

The last words were addressed to Theodoros, who had already been drawn to the window, as though to a lover, and was gazing out hungrily at the empty sea. He dragged himself away unwillingly and followed the Count, as befitted his role of the perfect servant. He returned in a short whole with Athanasius, the two of them carrying a heavy table which they placed in the window. This was followed by a variety of toilet articles and linen, slightly but not impossibly worn.

While he busied himself making the room more or less habitable, Athanasius chatted away, thoroughly enjoying the sight of new faces and the opportunity of having a foreign lady to serve, but the more expansive he became, the more Theodoros withdrew into his shell.

'Almighty God!' he cried at last, when the little man urged him to come and help in making up the bed, 'we are only staying a few hours, brother! One would think from the way you are going on we were to stay for months! Our brother Tombazis in Hydra should have got the pigeon and the ship may come at any moment now.'

'Even if your ship were to appear at this minute,' Athanasius responded peaceably, 'it would still be advisable for madame to play her part – you and she have been shipwrecked. You must be tired, exhausted. You need at least one night's rest. The Turks would not understand it if you flung yourselves on board the first vessel, without so much as pausing for breath. Odabassy Mahmoud is stupid – but not as stupid as that! Besides, it makes my master happy. Madame the Princess's coming here is to him a reminder of his youth. He has travelled in the west, you know, long ago, and visited the doge's court in Venice and the king of France.'

Theodoros gave a disgusted shrug.

'He must have been rich then! He doesn't seem to have much left.'

'More than you might think,' said Athanasius with a smile, 'but it is not good to tempt the enemy's greed. The master has known that for a long time. Indeed, it is the only thing he does remember clearly. And now,' he finished, beaming at Marianne, 'I am going to the Ursulines for a gown. It would be best if you came with me. No servant worthy of the name would remain with his mistress when she desires to rest.'

But the giant's patience was evidently at an end. With a furious gesture he flung the faded silk counterpane, which he had just taken off the bed, across the room.

'I was not made for this!' he shouted. 'I'm a klepht! Not a lackey!'

'If you shout like that,' Marianne observed coolly, 'every soul in the place will soon know it. You not only agreed to play the part – you actually asked for it. Personally, I should be very glad to part with you. You are a thorough nuisance!'

Theodoros glared at her from under his bushy brows, like a dog about to bite. She expected for a moment to see him bare his teeth, but he only growled:

'I have a duty to my country.'

'Then do it quietly. Did you notice the motto carved over the entrance as we came in? Sustine vel Abstine.'

'I don't know Latin.'

'Roughly speaking, it means: Stay the course or stay out. It's what I have been doing myself and I'd advise you to do the same. You are forever grumbling. Well, fate's not a matter of choice; it's something you put up with. Think yourself lucky if it offers you something worth fighting for.'

Theodoros flushed darkly and his eyes flashed.

'I've known that long enough,' he boomed, 'and no woman is going to teach me how to act!'

Under the shocked gaze of Athanasius, who clearly could not believe that anyone could be so rude to a lady, he rushed from the room, slamming the door thunderously behind him. The little steward shook his head and made his own way to the door but, before going out, he turned and bowed and there was a smile in his eyes.

'Your highness will agree with me that servants nowadays are not what they were.'

Marianne had been half afraid that Athanasius would come back with a monkish habit, but when he returned he brought a cloth-wrapped package, with the compliments of the Mother Superior, containing a pretty Greek dress made of a natural woven stuff embroidered in multicoloured silks by the nuns. With it, there was a kind of shawl to go over the head, and several pairs of sandals of various sizes.

It was all very different from Leroy's elegant creations, packed away in Marianne's trunks and now sailing somewhere in the hold of the American brig, destined to be sold for the benefit of John Leighton, along with the ancestral jewels of the Sant'Annas, but by the time she was washed, brushed and dressed, Marianne felt much more like her real self.

Furthermore, she felt almost well. The sickness which had made her suffer so horribly on board the Sea Witch had virtually disappeared and, but for the pangs of hunger which consumed her almost incessantly, she might almost have been able to forget that she was expecting a child and that time was not on her side. For, unless she got rid of it very soon, it would soon become impossible to do so without grave risk to her own life.

The room was afire with the glow of the setting sun. Down below, the harbour had come to life again. Boats were putting out for the night's fishing, and others returning, their decks armoured in shining scales. But they were all only fishing boats. There was no 'great ship worthy to carry an ambassadress', and as she leaned on the stone mullion, Marianne was conscious of a growing impatience, like that which devoured Theodoros. Him she had not set eyes on since his tempestuous exit a little while before, and she guessed that he was down by the waterfront, mingling with the people of the island – the island on which Theseus had abandoned Ariadne – scanning the horizon for the masts and yards of a big merchant vessel.

Would it ever come, this ship which a white pigeon had sped away to summon for her, to carry her to that almost legendary city where waited the golden-haired Sultana, on whom, unconsciously, she had begun to fasten all her hopes?

A hundred times over, since her reawakening to life and awareness in Melina's house, Marianne had told herself what she would do when she got there. She would go at once to the embassy and see Comte de Latour-Maubourg, and through him obtain an audience with the Sultana. Failing that, she would, if necessary, batter down the doors to carry her complaint to someone with the decency and power to scour the Mediterranean for the pirate's brig. The people of the Barbary coast were, she knew, great seamen; their swift-sailing xebecs and their means of communication were almost as efficient as anything possessed by Napoleon's highly-valued Monsieur Chappe. If they acted quickly, Leighton might find himself arrested off any port on the Mediterranean coast of Africa, hemmed in by a pack of hunters who would make him sorry he was ever born, while his unwilling passengers might yet be saved – if only there was still time.

Marianne's eyes grew moist at the remembrance of Arcadius, Agathe and Gracchus. She could not think of them without a deep sense of loss. She had never realized, when they were with her every day, how fond of them she had become. As for Jason, whenever he came into her mind – which was all too often – she exerted every ounce of will-power she possessed to drive him out again. How could she think of him without giving way to grief and despair, with all the torments of regret tearing at her heart? She no longer blamed him for his cruelty to her, or for the hurt that he had done her, admitting loyally that she had brought it on herself. If she had only trusted him more, if she had not been so terribly afraid of losing his love, if she had dared to tell him the truth about her abduction from Florence, if only – if only she had just a little bit more courage! If 'ifs' and 'ans' were pots and pans…

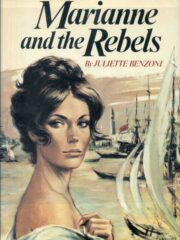

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.