She was within an inch of echoing Antigone's anguished cry: 'I was made for love, not for hate.' Yet it did her good to be the old Marianne again, with her hopeless rages, her miseries, quarrels and follies, just as she had derived comfort from the thought of her home and her cousin, even if it was only the comfort of regret.

So much had happened to her already, she had suffered such a variety of experiences, that her present situation was not really so much worse than it had been on other occasions in the past. Even the fact that she was pregnant by a man she loathed had ceased to matter so very much. That was now the least of her problems. A slightly philosophical note began to creep into her angry thoughts.

'All I need now,' she thought, 'is to find myself becoming a brigand chief! But with Theodoras perhaps that won't be so very far off!'

In any case, the important thing for the moment was how they were to get to Constantinople, wretched place! She had lost all her papers, passports, credentials, of course; everything had gone that could prove her identity. However, she knew herself to be equal to persuading the ambassador, at least, to recognize her, and there was a small inner voice which whispered to her, stronger than all the reason and logic in the world, that at all costs, somehow, she had to reach the Ottoman capital, if she had to travel on a fishing boat, or even swim! And Marianne had always placed great faith in her inner voices.

CHAPTER TEN

The Island Where Time Stands Still

Yorgo's boat cast off, slid over the dark water in the shadow of the cliffs and put to sea. The white figure of Melina Koriatis, standing in the entrance to the little cave that served as a discreet landing stage, receded and her waving hand was lost in shadow. Soon, even the cave mouth itself had disappeared.

Marianne sighed and huddled in the big black cloak given her by her hostess, seeking what shelter she could find from the spray in the lee of the heavy canvas that was laced across from side to side of the vessel to protect the cargo, in this case jars of wine.

The fisherman's boat was a scaphos, one of those curious and rather badly-built Greek vessels that have nothing essentially Mediterranean about them, save their gaudy sails: a jib and a big gaff mainsail rigged up to a yard of inordinate length. She rode very low in the water, amply justifying the expanse of canvas, especially at times like the present when there was a heavy sea running. It must have been blowing a gale somewhere, for the night was cold, and Marianne blessed the warm wool they had bundled her up in, over her tattered gown.

She had felt a little sad at parting from the woman called Sappho. She had liked the revolutionary princess with her strangeness and her courage, recognizing in her something akin to herself and to those other women she had known with the capacity to grasp life with both hands: women like her cousin Adelaide and her friend Fortunée Hamelin.

Their good-byes had been brief.

'We may meet again, perhaps,' Melina had said, shaking her hand with a firm grip, like a man's. 'But if our paths should not cross, then go with God.'

That was all, and then she had gone with them down the dark narrow staircase cut in the rock beneath the floor of the chapel in which Marianne had been housed.

The sight of Yorgo lifting up the heavy stone and sliding into the lightless hole with the ease of long practice had told Marianne all that she needed to know about how she had come to find a fish by her bed, but Melina had coolly furnished her with the details. It appeared that whenever Yorgo and his brother were landing contraband articles such as guns, powder, shot or similar items, they were in the habit of carrying it in their baskets, hidden under a batch of fresh fish, and bringing it up the steps under the chapel. These led down by means of a long and fairly gently sloping chimney cut in the rock to a cave, half-filled with water, where a fishing boat could tie up out of sight of anyone.

Running before a southerly wind that filled the sails and whipped up the sea, the scaphos made good speed along the east coast of Santorini, before heading straight out to sea. No one had said a word since they left the cave. The passengers sat apart from one another, as though in mutual distrust, and gave themselves up to the rhythm of the ship. Only Theodoros took his turn at the helm.

When he had turned up, earlier, with Yorgo, Marianne had scarcely recognized him. He was dressed in rags, much like those in which she herself had been decked, but his were half-concealed under a rough woollen blanket, and with his face covered by a flowing beard that joined his hair and obscured his moustache, he looked like some mad prophet. His appearance was certainly an unlikely one for the servant of a fashionable Frenchwoman, but it fitted perfectly the part of a recent castaway.

The story which had been concocted to explain Marianne's return to her ordinary life was a fairly simple one. On his way to Naxos with a cargo of wine, Yorgo was supposed to have found the Princess Sant'Anna and her servant adrift, clinging to a few spars, in the water between Santorini and Ios, the vessel in which they were travelling having been sunk by pirates – who apparently abounded in the islands and were perfectly capable of sinking any vessel which came in their way.

Once arrived in Naxos, where there was a considerable population of Venetian origin and where the Turks tolerated the existence of a number of Catholic communities, the fisherman would take the two 'castaways' to a cousin of his, a man called Athanasius, who acted in the ill-defined capacity of gardener, steward and man-of-all-work to the last descendant of one of the old ruling families of the island, a Count Sommaripa. He, naturally, could not do otherwise than offer the hospitality of his house to an Italian princess who found herself in difficulties, until such time as a vessel should put in at Naxos that could carry her to Constantinople. If the pigeon from Ayios Ilias had done its job properly, that ship should not be long in coming.

This business of the ship that was to come for her made Marianne uneasy. In her view, any vessel would have done as well, even a Turkish xebec. All she wanted was to get to the Ottoman capital as soon as possible, since that was the only place from which to begin her search for the Sea Witch. She did not see at all why it was necessary for her to arrive in a Greek vessel, unless her mysterious new friends had some ulterior motive. In which case, what was it?

Melina had told her that there was a Greek merchant fleet, based on the island of Hydra, which even the Turks would hesitate to attack. The men who manned it were trustworthy, and strangers to fear. They covered the islands and were able to drop anchor with impunity off the quays of Phanar, and they carried, as well as grain, oil and wine, many of the conspirators' hopes. Hydra had been the pigeon's goal.

In other words, Marianne told herself, they are almost certainly pirates got up as merchants. She was beginning to wonder if her name was going to be used to cover not just one rebel with a price on his head, but a whole ship's crew of them. By this time she was seeing rebels everywhere.

There was, in fact, another passenger who had embarked at the same time as herself and the alarming Theodoras, and Marianne was not unduly surprised to see beneath the fisherman's cap the face of the tall dark girl who had steadied her on the way back from the rock where Sappho sang her hymn to the setting sun.

Released from his classical draperies, the young guest revealed himself as nature intended: a slim, energetic boy with a keen face, who had smiled at her with cheerful complicity as he handed her into the boat. She now knew that he was a young Cretan called Demetrios whose father had been beheaded a year earlier for refusing to pay a tax, and that he was going now to take up a prearranged position in one of the mysterious places where the rebellion, which no Greek ever doubted would soon come, was slowly ripening to fruition.

The voyage passed off without incident. The sea subsided towards morning and, although as a result the wind abated somewhat, there remained enough of a steady breeze to bring the scaphos, by about midday, into line with the opening of the bay of Naxos. Directly ahead, beyond the dunes covered with long rippling grasses and a species of tall greenish lily, a little town lay glaring white and dozing in the sun, clinging to the sides of a conical hill on whose summit the inevitable Venetian fortress crumbled slowly beneath the disillusioned folds of the Sultan's green flag with its triple crescent.

On a tiny island just outside the harbour the white columns of a small abandoned temple also seemed to droop dispiritedly.

For the first time since they had set sail, Marianne approached Theodoros.

'Are we landing now? I thought we should have waited until nightfall?'

'What for? At this time of day, everyone's asleep – and sleeping much more deeply than at night. It's too hot for anyone to put their nose out of doors. Even the Turks are having a siesta.'

The heat was certainly intense. It was reflected back from the white walls with a ferocity that was almost unbearable and all other colours were bleached into the general all-prevailing whiteness. The air vibrated as though with the humming of invisible bees, and there was not a living soul to be seen on the baking quay. Every house was closely shuttered against the glare, and whenever they did catch sight of a human being it was of someone fast asleep on the ground, back against a wall and cap or turban pulled well down over his eyes, in the shade of a rose trellis or a dark doorway. It was the Sleeping Beauty's island. The entire harbour lay under a spell of sleep and every single creature in it was firmly resting.

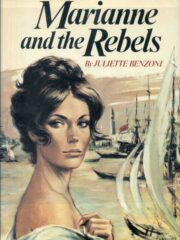

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.