'They can be dangerous. These things often end in tragedy.'

'As if I cared! Can't you understand I'd rather die a hundred times than give birth to this – oh, Arcadius! It's not my fault but it disgusts me! I thought I'd washed it all away, but it is too strong. It's come back and now it's taking possession of me! Help me, my friend… try and find me some potion, anything…'

Her head on her knees, cradled in her folded arms, she had begun to cry soundlessly, and to Jolival that silence was worse than any sobs. Marianne had never seemed to him more wretched and defenceless than she was then, finding herself a prisoner of her own body, the victim of a mischance which could cost her all her life's happiness.

After a moment, he sighed. 'Don't cry. It does no good and will only make you ill. You must be brave if you are to overcome this new ordeal.'

'I'm tired of ordeals,' Marianne cried. 'I've had more than my share.'

'Maybe so, but you've got to go through with this one, all the same. I'll try and see if it's possible to find what you want on this island but it's not going to be easy and we haven't much time. The language they talk in these parts nowadays hasn't much in common with the Greek of Aristophanes that I learned at school, either, but I'll try, I promise you.'

Feeling a little calmer now that she had shared some of her anguish with her old friend, Marianne managed to get a good night's sleep and woke the next morning so completely refreshed that she was seized with doubts. Perhaps, after all, her faintness had been due to some quite different cause? There was certainly a most unpleasant smell of oil about the harbour. But in her heart she knew that she was trying to deceive herself with false hopes. There was the physical proof whose presence, or more precisely absence, corroborated all too surely her own spontaneous diagnosis.

As she got out of her bath, she stood for a moment staring at herself in the mirror with a kind of horrified disbelief. It was much too soon as yet for anything to show. Her body looked the same as ever, just as slim and unmarked, and yet she felt for it the kind of revulsion inspired by a fruit that looks perfect outside yet is eaten away by maggots within. She almost hated it. It was as though, by admitting an alien life to enter and grow there, it had somehow betrayed her and become something apart from herself.

'You're coming out of there,' she threatened under her breath. 'Even if I have to have a fall or climb the masthead to do it. There are a hundred ways of getting rid of rotten fruit, as Damiani knew when he tried to keep his eye on me.'

With this object in mind, she began by asking her hostess if it were possible to have the use of a horse. An hour or two's gallop could have amazing results for one in her condition. But when she asked the question, Maddalena looked at her with eyes wide with astonishment.

'Horse riding? In this heat? We have a little coolness here but the moment you are out of the shade of the trees—'

'I'm not afraid of that, and it is so long since I was on horseback that I'm aching for a mount.'

'You're a perfect amazon,' laughed the Countess. 'Unfortunately there are no riding horses here, apart from those belonging to the officers of the garrison. Only donkeys and a few mules. They are all very well for an airing, but if it's an intoxicating gallop you're after, you'd have a job persuading them to do more than a sedate trot. The ground here is generally too steep. But we can go out in the carriage as often as you wish. The country is very beautiful and I should enjoy showing it to you.'

Disappointed in this direction, Marianne agreed readily to everything her hostess had to offer in the way of distraction. She went with her for a long drive through narrow valleys covered with bracken and myrtle where it was deliciously cool, and along the sea shore on to which the Potamos valley and the Alamano's garden debouched. She saw with delight the tiny island of Pontikonisi in its dreamlike bay and the tiny monastery of Blachernes, looking like a small white ink-pot left lying on the surface of the water, with a huge cypress, like a back quill, beside it. They paid a call on the Governor, General Donzelot, at the Fortezza Vecchia and he took them on a tour of inspection and gave them tea.

Marianne inspected the old Venetian cannon and the bronze statue of Schulenburg who had defended the island against the Turks a century before, flirted mildly with a number of young officers of the 6th Regiment of the Line who were visibly dazzled by her beauty, and was generally charming to everyone presented to her, promised to attend the next performance at the theatre which was the garrison's chief amusement, and finally, before returning to Potamos where the Alamanos were holding a grand dinner party in her honour, knelt for a few moments before the sacred relics of St Spiridion.

St Spiridion had been a Cypriot shepherd who rose, by reason of his virtue and ability, to be Bishop of Alexandria. His mummified body had been acquired from the Turks by a Greek merchant who gave it as a dowry with his eldest daughter on the occasion of her marriage to an eminent Corfiot named Bulgari.

'And ever since then, there has always been a priest in the Bulgari family,' Maddalena concluded in her vivacious way. The one who showed you the relic and took some money from you is the latest.'

'Why? Have they still such reverence for the saint?'

'Well, yes, of course. But it's more than that. St Spiridion represents the greater part of their income. They didn't give him the Church, they only, as it were, hired him out. Rather a come-down for a great saint, don't you agree? Not that he doesn't answer prayers just as well as any of the rest. He's a splendid saint, for he doesn't seem to bear a grudge at all.'

Even so, Marianne dared not ask the one-time shepherd to intercede for her. Divine aid was not for her in the deed she contemplated. That was more a matter for the devil.

The grand dinner at which she was the guest of honour in white satin and diamonds seemed to her quite the longest and most boring she had ever sat through. Jolival had departed that morning first thing for the other end of the island to inspect the excavations which General Donzelot was undertaking there. Jason and his officers had been invited but had declined, pleading the urgency of the repairs to the ship, and Marianne, having waited all day in eager anticipation of the evening which would bring her reluctant lover to her, was hard put to it to conceal her disappointment and maintain a smiling face and an air of interest in what her neighbours were saying to her. The left-hand neighbour, at least, for on her right she had General Donzelot who was a man of few words. Like most men of action, Donzelot hated wasting time in conversation. He was polite and friendly but Marianne could have sworn that he shared her own opinion of this dinner as nothing but a tiresome duty.

Her other neighbour, by contrast, was indefatigable. He was a local notable whose name she had already forgotten, and he entertained her, in the most gruesome detail, with an account of the epic battles he had fought in his younger days against the ferocious troops of the Pasha of Yannina during the Souliot rising. Now, if there was one thing Marianne loathed, it was listening to people recounting their experiences of war. She had had more than enough of that at Napoleon's court where there was scarcely a man without a tale to tell.

Consequently it was with a sense of relief that she regained her own room when the evening came to an end at last and delivered herself up to Agathe's hands to be divested of her finery. Enveloped in a lace-trimmed wrapper of fine lawn, she was settled on a low chair to have her hair brushed for the night.

'Monsieur de Jolival is not back yet?' she asked Agathe who was busy with two brushes shaking out the hair which had been bound up all day long.

'No, my lady. At least, that is to say he came in while you were all at dinner, just to change. And I must say, he needed to! His clothes were all white with dust. He said not to disturb anyone on his account because he was going straight out again and would get his dinner down at the harbour.'

Marianne closed her eyes, satisfied, and abandoned herself to her maid's deft fingers with a deep sense of reassurance. Jolival was doing his best for her, she was certain. He had not gone down to the harbour for the sake of entertainment.

After a few minutes she told Agathe that she might stop now and go to bed.

'Don't you want me to plait your hair for you, my lady?'

'No, thank you, Agathe. I'll leave it loose tonight. I've a trifle of a headache and would rather be alone. I shan't go to bed yet.'

When the girl, who was accustomed to asking no questions, had dropped a curtsy and left her, Marianne went to the long window opening on to a small balcony and, taking down the screen of mosquito netting, stepped outside. She felt stifled and in need of air. The screens were a good protection against the insects but they also seemed to prevent the free circulation of air.

Tucking her hands into the wide sleeves of her wrapper, she moved across the balcony. It was much warmer than it had been the night before. Not a breath of wind had come at nightfall to cool the parching atmosphere. Earlier, at dinner, she had felt as if her satin dress were sticking to her skin. Even the stone balustrade on which she was leaning was still warm.

Out of doors, though, the night was glorious: an eastern darkness, rich with stars and heavy with perfume, ringing with the rhythmic note of cicadas. Down below, thousands of glow-worms made a second firmament of the dark shapes of trees and shrubs, while at the foot of the valley the sea gleamed softly, a silvered triangle framed by the tall spires of cypress trees. Except for the plaintive scraping of the cicadas and the faint swish of the sea on the pebbled shore, there was not a sound to be heard.

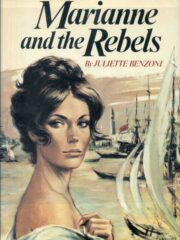

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.