This approach made Marianne uneasy. She knew Napoleon too well not to feel some alarm at the idea of orders concerning herself and given to no less a person than the Duke of Padua. This was unusual. Still dwelling on what the Emperor of the French might have in store for her now, she merely remarked 'Indeed?' in a tone so preoccupied that Arrighi stopped dead in the centre of the avenue, obliging her to do the same.

'Princess,' he said concisely, 'I am aware that you find this interview tiresome and would ask you to believe that I should greatly prefer to engage you in idle talk. A stroll in your company and in such pleasant surroundings would be most enjoyable. However, I regret that I must request you to give me your full attention.'

Why, thought Marianne, more amused than embarrassed, the man is angry! What a hot-tempered race these Corsicans are, to be sure!

But because she knew that she had been less than polite, she bestowed on him a mollifying smile of such brilliance that the soldier's stern face flushed.

'Forgive me, General. I did not mean to offend you, but I was deep in thought. It always makes me anxious, you know, when the Emperor goes to the trouble of giving special orders which concern me. His Majesty's… er… solicitude is apt to be somewhat demanding.'

As abruptly as his earlier move to anger, Arrighi now gave a bark of laughter and, repossessing himself of Marianne's hand, he carried it to his lips before tucking it back within his own.

'I quite agree,' he said cheerfully. 'It is always unnerving. But if we are friends?'

Marianne smiled again. 'We are friends.'

'Then, if we are friends, listen to me for a moment. My orders are to escort you personally to the Sant'Anna palace and, once within your husband's domain, not to let you out of my sight. The Emperor told me that you had some private matter to settle with the Prince, but one in which he too should have a say. He wants me, therefore, to be present at the interview with your husband.'

'Did the Emperor tell you that it is highly unlikely that you, any more than I myself, will be privileged to see Prince Sant'Anna with your own eyes?'

'Yes. He told me. Nevertheless, he wants me to hear at least what the Prince says to you, and what he wants of you.'

'He may,' Marianne said hesitantly, 'he may simply want me to stay with him?' This was her deepest and most dreadful fear, for she did not see how the Emperor's protection could prevent the Prince from keeping his wife at home.

'Then that's precisely where I come in. The Emperor wishes me to convey to the Prince his express wish that your meeting today shall be a brief one – a few hours at most. It is designed merely to show him that the Emperor accedes to his request and to allow you both to reach some agreement about the future. For the present—'

He paused and taking a large white handkerchief from his pocket mopped his brow with it. Even under the green roof of trees the heat made itself felt and in the heavy uniform, made heavier still by its weight of gold braid, it must have been very nearly intolerable. But Marianne pressed him to go on. She was beginning to find their conversation more and more interesting.

'For the present?'

'The present, madame, belongs neither to the Prince nor to yourself. The Emperor has need of you.'

'Has need of me? But what for?'

'I think this will explain.'

A letter sealed with the imperial cipher had appeared, as if by magic, between Arrighi's fingers. Marianne regarded it for a moment before taking it with an expression of such deep distrust that the general smiled.

'Don't be afraid. It won't explode.'

'I'm not so sure.'

Marianne took the letter to an old stone seat at the foot of an oak tree and sat down, her dress of rose-pink lawn spread like a graceful corolla around her. She slid nervous fingers under the seal of wax, unfolded the letter, and began to read. Like most of Napoleon's letters, it was brief.

'Marianne,' the Emperor had written, 'it occurs to me that the best way to protect you from your husband's resentment is to enlist you in the service of the Empire. You left Paris under cover of a somewhat vague diplomatic mission, now you have a real one, of great importance to France. The Duke of Padua, who is under orders to see that nothing occurs to interfere with your departure, will convey to you my detailed instructions concerning your mission. I look to you to prove yourself worthy of my trust and that of all Frenchmen. I shall know how to reward you. N.'

'His trust? The trust of all Frenchmen? What does it all mean?' Marianne managed to ask.

There was a world of bewilderment in the eyes she lifted to Arrighi's. She was half inclined to think Napoleon must have gone mad. To make sure, she re-read the letter carefully, word by word, under her breath, but this second perusal only confirmed her in the same dismal conclusion, which her companion had no difficulty in interpreting from her expressive face.

'No,' he said coolly, seating himself beside her. 'The Emperor is not mad. He is merely trying to gain time for you, once your husband has made his intentions clear to you. The only way to do that was to enroll you in his own diplomatic service, which is what he has done.'

'Me, a diplomat? But this is absurd! What government would listen to a woman?'

'The government of another woman, perhaps. In any case, there's no question of making you an official plenipotentiary. The service his Majesty requires of you is of a more… secret nature, such as he reserves for those most in his confidence and for his closest friends…'

'I dare say,' Marianne broke in, fanning herself irritably with the imperial letter. 'I have heard a good deal about the "immense" services which the Emperor's sisters have rendered him in the past, in a sphere which I find less than attractive. So let us come to the point, if you please. Just what is the Emperor asking me to do? And, more important, where is he sending me?'

'To Constantinople.'

If the great oak under which she sat had fallen on her, Marianne could not have been more astonished. She stared up at her companion's expressionless face, as though searching for some reflection of the brain fever to which, she was persuaded, Napoleon must have succumbed. But not only did Arrighi appear perfectly composed and self-possessed, he was also taking her hand in a grasp that was as firm as it was understanding.

'Hear me calmly for a moment and you will see the Emperor's idea is not so foolish after all. I might even go so far as to say that it's the best thing for you and for his policies in the present circumstances.'

Patiently, he outlined for his young hearer's benefit the European situation in that spring of 1811, and in particular the relations between France and Russia. Relations with the Tsar were deteriorating rapidly, despite the great maritime reunions at Tilsit. The barque of understanding was adrift. Although Alexander I had practically refused his sister Anna to his 'brother' Napoleon, he nevertheless regarded the Austrian marriage askance, nor had his view been improved by the French annexation of his brother-in-law's grand duchy of Oldenburg and of the Hanseatic towns. He had expressed his displeasure by reopening his ports to English shipping and by slapping heavy duties on goods imported from France, and prohibitive dues on the ships which carried them.

Napeoleon had countered by taking notice at last of the precise activities in which the handsome colonel Sasha Chernychev was indulging at his court, maintaining a satisfying spy network through the agency of various pretty women. The police had descended without warning on his Paris house. Even so, they were too late. The bird had flown. Warned in time, Sasha had elected to disappear, without hope of return, but the papers found there had told their own tale.

These circumstances, combined with the lust for power of two autocratic rulers, made war appear inevitable to attentive observers. Russia, however, had already been at war, since 1809, with the Ottoman Empire over the Danube forts: a war of attrition but one which, thanks to the strength of the Turkish forces, was keeping Alexander and his army fully occupied.

'That war must go on,' Arrighi said forcefully. 'It will keep a large part of the Russian forces busy on the Black Sea while we march on Moscow. The Emperor does not mean to wait until the Cossacks are on our doorstep. This is where you come in.'

Marianne had listened with considerable relish to the tale of her old enemy Chernychev's present troubles, aware that his barbarous treatment of herself had probably played its part in bringing those troubles upon him, but this was not enough to make her bow to the imperial commands without further question.

'Do you mean that I'm to persuade the Sultan to continue the war? But you must have thought that—'

The general interrupted her with some impatience.

'We have thought of everything. Including the fact that you are a woman and that, as a good Muslim, the Sultan Mahmud regards women in general as inferior creatures with whom it is not proper to negotiate. Consequently, it is not to him you go but to the Haseki Sultan. The Empress Mother is a Frenchwoman, a Creole from Martinique and own cousin to the Empress Josephine, with whom she was for some time brought up. There was a great bond of affection between them as children, a bond which the sultana has never forgotten. Aimée Dubucq de Rivery, whom the Turks call Nakshidil, is not only a woman of great beauty but also an extremely active and intelligent one. She has a long memory too, and has never accepted the Emperor's repudiation of her cousin and his remarriage. Since she has great influence over her son Mahmud, who worships her, this has led to a distinct chill in our relations. Our ambassador, Monsieur Latour-Maubourg, is at his wits' end and crying out for help. He can no longer even obtain an audience at the Seraglio.'

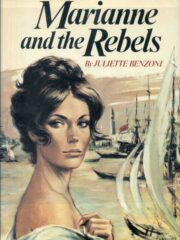

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.