Yet, as she climbed the stone steps, Marianne found all her courage and fighting spirit come flooding back. As always with her, the imminent prospect of danger galvanized her and restored the equilibrium which waiting and uncertainty invariably drained away. She knew, could feel, with an almost animal instinct she had, that danger lurked behind the delicate old-world graces of that building, even if it were no more than the horrible memory of Lucinda the Witch, whose house this might once have been. For, if Marianne's recollections were correct, this must be the Palazzo Soranzo, the birthplace of that terrible princess. She nerved herself for the fight.

The vestibule which opened before her was so sumptuous as to take her breath away. Great gilded lanterns of exquisite workmanship, which must have originated in some ancient galley, threw moving patterns on the many-coloured marble floors, flowery as a Persian garden, and on the gilding of a ceiling with long, painted beams. The walls were covered with a succession of vast portraits and lined with imposing armorial benches, alternating with porphyry chests where miniature caravels spread their sails. The portraits were all of men and women dressed with unbelievable magnificence. There were even two of doges in full dress, the corno d'oro on their heads, pride in their faces.

The seafaring associations of the gallery were plain and Marianne was surprised to catch herself thinking that Jason or Surcouf might have liked this house, so dedicated to the sea. Alas, it was as silent as a tomb.

There was not a sound to be heard except the newcomers' own footsteps. In a little while this had become so ominous that even Giuseppe seemed aware of it. He coughed, as though to reassure himself, and then, going to a double door about halfway along the gallery, he whispered, as though in church:

'My mission ends here, Excellenza. May I hope that your ladyship will not think too hardly of me?'

'And of this charming journey? Rest assured, my friend, that I shall dwell on it with the greatest of pleasure – supposing I have the time to dwell on anything, that is!' Marianne spoke with bitter irony.

Giuseppe bowed without answering and withdrew. Yet the double doors were opening, creaking a little but to all appearances without human aid.

Beyond lay a room of impressive dimensions, in the centre of which was a table laid for a meal, with an almost unbelievable magnificence. It was like a field of gold: plates and dishes of chased gold, enamelled goblets, jewelled flagons, the whole adorned with wonderful purplish roses, and tall branched candlesticks spreading their burden of lighted candles gracefully over this almost barbaric splendour, while outside the ring of light the walls hung with antique tapestries and the priceless carved chimneypiece lay in deep shadow.

It was a table set for a banquet, and yet Marianne shivered as she saw that it was set with only two places. So… the Prince had decided to show himself at last? What else could be the meaning of those two places? Was she to see him, at last, as he was, hideous as that reality might be? Or would he still wear his white mask when he came to take his seat here?

Despite herself, she felt fear clawing at her heart. She knew now that however much her natural curiosity might urge her to penetrate the mystery with which her strange husband surrounded himself, since that night of magic she had always feared, instinctively, to find herself alone and face to face with him. Yet surely that table, with its flowers, could not portend anything so very terrible! It was a table laid to please, almost a table for lovers.

The double doors through which Marianne had entered closed with the same creaking. At the same time another door, a little, low one at the side of the hearth, opened slowly, very slowly, as though at some well-timed dramatic highlight in the theatre.

Marianne stood rooted to the spot, her eyes wide and her fingers tensed, sweat starting on her brow, watching it as it swung on its hinges, so much as she might have stared at the door of a tomb about to deliver up its dead.

A glittering figure appeared in silhouette, too far from the table to be seen clearly. Lit only from behind, by the light in the next room, it was the figure of a stockily-built man dressed in a long robe of cloth of gold. But Marianne saw at once that it was not the slender figure of the man who had mastered Ilderim. This man was shorter, heavier, less noble. He came forward into the huge dining-room and then, with anger and disbelief, Marianne saw Matteo Damiani, dressed like a doge, step forward into the pool of light surrounding the table. He was smiling…

CHAPTER THREE

Slaves of the Devil

Prince Sant'Anna's steward and trusted agent advanced with measured tread, hands folded in the wide sleeves of his dalmatic, and coming to one of the tall, red chairs drawn up to the table laid one beringed hand on its back while with the other he made what was intended as a gracious gesture towards the remaining place. The smile was like a mask affixed to his face.

'Be seated, I beg, and let us eat. You must be tired after the long journey.'

For a moment it seemed to Marianne that her eyes and ears must be deceiving her but it was not long before she knew that this was no evil dream.

The man who stood before her was indeed Matteo Damiani, the dangerous and untrustworthy servant who, on one night of horror, had almost been her murderer.

She had not seen him since that dreadful moment when he came towards her, hands outstretched, like a man in a trance, with murder in his eyes from which all human feeling had gone. But for the appearance of Ilderim and his tragic rider—

But at that fearful recollection, Marianne's fear very nearly became panic. She had to make a superhuman effort to fight it off and even to succeed in concealing what she felt. With such a man, whose frightening past history she knew, her one chance of escape lay precisely in not letting him see her terror of him. If he once knew she feared him, her instinct told her, she was lost.

Even now she still did not understand what had happened, or by what species of magic Damiani was able to parade himself like this, dressed up as a doge (she had seen the same costume on one of the portraits in the hall), in a Venetian palace where he gave himself all the airs of being master, but this was no time to indulge in speculation.

Instinctively, she attacked.

Folding her arms coolly, she eyed him with unconcealed scorn. Her eyes narrowed to glittering green slits between the long lashes.

'Does carnival in Venice continue into May?' she asked bluntly. 'Or are you going to a masquerade?'

Taken unawares, perhaps, by the sarcastic tone, Damiani gave a short laugh but, unprepared for an attack in this direction, he glanced uncertainly, almost with a shade of embarrassment, at his costume.

'Oh, the gown? I donned it in your honour, madame, just as I had this table set for your pleasure, to make your arrival in this house a celebration. I thought—'

'I?' Marianne broke in. 'I do not think I can have heard you correctly, or you so far forget yourself as to put yourself in your master's place. Recollect yourself, my friend. And tell me where is the Prince? And how comes it that Dona Lavinia is not here to welcome me?'

The steward drew out the chair before him and sank into it so heavily that it groaned under his weight. He had put on flesh since that terrible night when, maddened by his occult practices, he had attempted in his rage to kill Marianne. The Roman mask, which had then lent his face a certain distinction, was now melted into fat, and his hair, once so thick, was thinning alarmingly, while the fingers loaded with such vulgar profusion of rings had become like bloated sausages. But there was nothing in the least laughable or absurd about the pale, impudent eyes in that fat, ageing body.

'Eyes like a snake,' Marianne thought with a shiver of revulsion at the cold cruelty they revealed.

The smile had faded, as if Matteo no longer considered it worth while to maintain the fiction. Marianne knew that the man before her was her implacable enemy, and it came as no surprise to her to hear him say:

'That fool Lavinia! Pray for her, if you like. Myself, I had enough of her lectures and her pious airs – I—'

'You killed her?' Marianne exclaimed furiously, conscious of both outrage and a wave of grief as bitter as it was unexpected. She had not known that she had allowed the quiet housekeeper become so dear to her. 'You were base enough to murder that good woman who never did anyone any harm? And the Prince did not shoot you dead like the mad dog you are?'

'He might have done so,' Damiani growled, 'had he been in a position to.' He started to his feet with a violence that set the heavily laden table rocking and the golden vessels clinking. 'I did away with him first. It was time,' he added, thumping the table with his fist to emphasize his words, 'high time I took my rightful place as head of the family!'

This time, the blow went home, with such force that Marianne reeled as though she had been struck, and uttered a moan of horror.

Dead! Her strange husband was dead! The prince in the white mask, dead! Dead, the man who on that stormy night had taken her trembling hand in his, dead, the wonderful horseman whom even from the depths of her fear and uncertainty, she had admired! It was not possible! Fate could not deal her such a scurvy trick.

'You're lying,' she said in a voice that was firm, though drained of all expression.

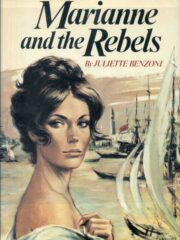

"Marianne and the Rebels" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Rebels". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Rebels" друзьям в соцсетях.