He indicated the rope ladder, now banging in the rising wind, that climbed the sheer sides of the brig above them. But even as he spoke men were descending on the deck from the American vessel, hoisting up their captain like a parcel. Ledru's men, reaching out to shake Jason's hand in a crushing grip as he was borne past, held the ladder stiff and steady.

Leaning against Jolival, Marianne watched his progress, following him with her eyes until he reached the frieze of human heads and bodies lining the rail above. Jason's arrival on deck was the signal for a rousing cheer which rang like a death knell in Marianne's already breaking heart. To her, it sounded like the voice of that distant country of his, claiming him from her, back again to a place where she was not allowed to follow.

Meanwhile, Vidocq had gone to the lugger's stern and signalled three times by opening and closing the shutter of a lantern, and away beyond the promontory of rocks the frigate was already going about for Brest. Already, the sky above the coast was almost imperceptibly lighter, though the wind was strengthening, filling the sails as they were set once more, and the lugger's crew, armed with long gaffs, fended her off from the brig's side. Jean Ledru was back at the tiller and, slowly, inexorably, the gap of water between the two vessels widened. The lugger slipped astern of the great sailing ship and lay for a moment in the pool of light cast by her two gilded stern lanterns. And there, high above her as she stood unable any longer to restrain her tears, Marianne saw Jason, his tall figure supported by his own men. He raised one arm in a gesture of farewell, but already he seemed very far away… so far, indeed, that for a moment Marianne forgot the promise she had made only a moment before, forgot to be brave, forgot that this parting was not good-bye but only au revoir. She was only a desperate broken woman, seeing the best part of herself borne away from her on the wind. With a last, terrible effort, she tore herself from Jolival's comforting arms and flung herself at the rail.

'Jason!' she screamed, oblivious of the tossing bow wave which drenched her in spray. 'Jason!… Come back!… Come back!… I love you…'

She clung with dripping fingers to the slippery wood, tossing back the sodden tangles of her hair in an automatic gesture. The lugger plunged deeply into a trough of the waves, nearly sending her sprawling on the deck, but all the strength that she possessed was in her clinging hands, her whole life in the eyes which still gazed at the fast-dwindling shape of Jason's ship. At last, two strong arms came to encircle her, drawing her back from her desperate watch, and from the peril in which she stood.

'Are you out of your mind?' Vidocq's voice scolded. 'Do you want to fall overboard?'

'I want to see him again… I want to be with him!'

'And he with you! But it's not a corpse he'd hope to find, it's you, yourself, alive! Good God! Do you want to die before his eyes to prove your love? For the love of heaven, live! Live at least until the time he appointed for your meeting.'

Marianne's eyes widened in amazement. Already the instinct for life was reviving in her, willing her to fight on towards the goal which at this moment had eluded her.

'How did you know?'

'He loves you. He would never have parted from you without something of the kind. Now go and get under cover. You are soaking wet and the dawn mist is rising. It's as easy to die of an inflammation of the lungs as it is by drowning.'

She submitted docilely when he led her to a more sheltered spot on the deck and wrapped a heavy canvas sailcloth about her, but rejected all attempts to make her go below. While Jason's ship was still there to be seen, she was determined not to lose sight of it.

Far out, near the islands with their attendant train of rocky reefs and islets, the Sea Witch was heading out to sea, dipping gracefully under the frail, towering white peaks of her crowded sails. In the grey light of dawn, she looked like a gull, gliding among the black rocks. For a moment, as the vessel went about to pass between two jagged islets, she presented herself to Marianne's eyes broadside on and she recalled then what it was that Talleyrand had told her one day about that figure shaped like a woman on the prow. He had said that the figurehead was carved in her own image, that Jason had had it made to adorn the prow of his ship, and Marianne found herself wishing passionately that she could be that woman made of wood whom he had caused to be created, and on whom his eyes must often rest.

A moment later, the American brig had gone about again and nothing more remained to be seen but the stern, with its two lanterns vanishing into the mist.

Sighing, Marianne made her way to where Surcouf and Jolival were sitting, talking quietly together, on some coils of rope while all around them was the slap of the sailors' bare feet as they went about their duties. In a little while now, the carriage would be bearing her back to Paris, as Vidocq had said, back to Paris and the Emperor. She wondered why he should want to see her. Barely recalling now that she had ever loved him, Marianne could think only that she had no desire to see Napoleon.

Three weeks later, as her chaise clattered under the gateway of the chateau of Vincennes, Marianne glanced up at Vidocq with an expression full of alarm.

'Do your orders say I must be put in prison?' she asked.

'Good heavens, no! It is the Emperor's wish to grant you an audience, that is all. It is not for me to know his reasons. All that I can tell you is that my mission ends here.'

They had completed their journey from Brittany the night before and as he set Marianne down at her own door Vidocq had told her that he would come for her the following evening to take her to the Emperor, adding that court dress was not necessary but that she should be sure to wrap up warmly.

She had been a little mystified by this advice but too tired to ask any questions. Nor had she waited to interrogate Jolival. Instead, she had gone straight to bed, like a drowning sailor clutching at a raft, to recruit her strength for whatever was to come, little enough though it might interest her. Only one thing held any meaning for her: three weeks had gone by, three dreadful weeks spent jolting over the endless roads which the bad weather had made more trying even than usual, on a journey rendered hideous by every conceivable kind of unpleasantness, from lost wheels and broken springs to horses that slipped and fell and trees blown across the road. Yet for all this it was three weeks gone from the six months at whose end Jason would be waiting for her.

When she thought of him, which she did every hour, every second of her waking day, it was with a curious feeling of emptiness, like a painful, insatiable hunger which she tried to satisfy by letting her mind dwell constantly on the few, so very few moments when he had been there, close to her, so close that she could touch him, hold his hand, stroke his hair and smell the odour of his skin, the comforting warmth of him and the strength with which, even in his weakened state, he had crushed her to him and pressed that last kiss upon her lips, the kiss whose memory burned her still, and sent a tremor through all her limbs.

They had found Paris deep in snow. The bitter cold froze the water in the gutters, nipping ears and reddening noses. Miniature icebergs floated on the grey, bustling waters of the Seine and there were rumours that people in the poorer districts were dying of cold at nights. Everything was buried under a thick, white blanket which soon became stained and dirty but did not melt, leaving the gardens dressed in a cloak of dazzling white ermine while it transformed the streets into deadly, frozen sewers where it was the easiest thing in the world for anyone to break a leg. Even so, Marianne's horses, frost-nailed, had negotiated the long road from the rue de Lille to Vincennes without mishap.

The ancient fortress of the kings of France had risen suddenly out of the night, grim and uncared-for, its towers demolished now to the level of the walls. Two only remained intact, the village tower bestriding the ancient drawbridge, and the enormous square keep, its dark bulk rising high above the bare trees, flanked by its four corner turrets. Vincennes was an arsenal, its storehouses guarded by veterans no longer fit for active service and a handful of regular troops, but it was also a state prison and the keep itself was strongly fortified.

Yet now it stood, silent within the circle of its curtain wall, cut off on the right hand by the barbican from the wide, white courtyard where the snow-covered piles of ammunition were like odd, conical cream cakes. Opposite was the derelict chapel, beautiful in the frayed lacework of crumbling stone, decaying slowly because no one thought of repairing it, a precious jewel to St Louis but neglected now, in these days of little faith. And Marianne searched her mind in vain for any reason for this audience, held in the secrecy of this rotting fortress with its sinister reputation. Why Vincennes? Why at night?

At a little distance, a noble pair of twin pavilions faced each other, evoking memories of the Grand Siècle of Louis XIV, although they had fared no better than the rest of the buildings. Panes of glass were missing from the windows, the mouldings of the mansard roofs were broken and the walls seamed with cracks. Yet it was towards the left-hand one of these two that Gracchus, acting on Vidocq's instructions, now turned his horses.

There was a faint light showing on the ground floor, behind the blackened windows. The chaise stopped, and Vidocq jumped out.

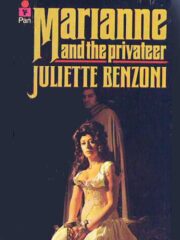

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.