'Particularly after the reek of the last few weeks. Human dirt and human wretchedness – it's the worst stench I know. Worse even than the stink of corruption because corruption is at least new life beginning. Try and forget – put it out of your mind. For you, it's all done with.'

'For you also, François.'

'Who can tell? I was not made for the wide open spaces but for the small world of men's thoughts and instincts. The elements may do very well for you. For myself, I prefer my fellow men. It's not as beautiful, but a lot more varied.'

'And more dangerous. Don't try to be too independent, François. Freedom is the one thing you have always lived for. You would find it in my country.'

'It depends what you mean by freedom…' Changing his tone abruptly, he asked: 'How long before we make Le Conquet?'

Jean Ledru answered him:

'We've a fair wind. In an hour, I'd say. It's not much above fifteen mile.'

They had run up a topsail and a flying jib to the bowsprit and the little craft was now carrying all her canvas, skimming the waves like a gull. On their starboard side, the coast fled past with now and then the squat belfry and roof of a church just visible, or the curious, angular shape of a dolmen. Pointing to one of these, Jean Ledru told Marianne: 'The legend has it that on Christmas Eve, when the clocks strike twelve, the dolmens and the menhirs go down to the sea to drink, leaving all their fabulous treasures uncovered. But woe betide anyone who tries to rob them if he is not quick enough, for on the last stroke they all return to their places, crushing the thief who may be caught inside.'

Marianne laughed, feeling again the pull of a good story which had always formed so strong an aspect of her appetite for life.

'How many legends are there in Brittany, Jean Ledru?'

'As many as the pebbles on the beach, I think.'

The beam of a lighthouse shone out suddenly through the darkness, yellow as an October moon, brooding over the jumbled mass of a huge, rocky promontory nearly a hundred feet high. Their youthful captain jerked his head towards it:

'St Mathieu's light. It is one of the westernmost points of Europe. There used to be a rich and powerful abbey there…'

As he spoke, a faint, uncertain shaft of moonlight filtered through the clouds and showed them the skeleton of an immense church and a great range of ruined buildings spreading out before the lighthouse, giving to that bare headland so gloomy and desolate an air that the sailors crossed themselves instinctively.

'Le Conquet is about a mile and a half to the north of here, is it not?' Vidocq asked, but Jean Ledru made no answer. He was searching the sea ahead. Then, just as the vessel rounded the point, her nose pointing out to sea, the shrill voice of the ship's boy rang out from the masthead:

'Sail ho, on the starboard beam!'

Everyone sat up and looked. Not more than a few cables' lengths away was the dainty outline of a brig, beating up wind with all sails flying in these perilous waters as surely as any fishing boat. Jean Ledru's voice rose above the wind: 'It's them! Get out the riding light!'

Marianne, like the rest, was watching the beautiful craft as it bore down on them, knowing that this was the rescue ship Surcouf had promised. Only Jason had not stirred but lay still, staring up at the sky, locked in a dream of sheer exhaustion. At last Ledru spoke impatiently:

'Well, Beaufort, take a look! It's your ship…'

A tremor ran through the privateer and he started to his feet then and remained, clinging to the rail, staring wide-eyed at the approaching vessel.

'The Witch!' His voice was husky with emotion. 'My Witch . ..'

Seeing him get to his feet, Marianne had followed, instinctively, and now standing next to him, she too stared:

'You mean – that ship is your own?'

'Yes… she is mine! Ours, Marianne! Tonight has given me back the two things I had thought lost for ever: you, my love… and her!'

There was such tenderness in that one short word that for a moment Marianne felt a stab of jealousy. Jason talked of the ship as he might have spoken of his own child. As if, instead of wood and metal, it had been made of his own blood and bone and his joy in looking at it was a father's joy in his child. She tightened the clasp of her hand on his, as though unconsciously trying to regain possession of him, but Jason's whole being was straining towards his ship so that he did not even seem to notice. He turned his head and looked at Jean Ledru, saying sharply:

'Do you know who is sailing her? Whoever he is, he is a master of his trade.'

Jean Ledru uttered a laugh of mingled pride and triumph:

'I'll say he is! A master indeed! It is Surcouf himself! We lifted your ship for you from under the very noses of the excisemen in Morlaix river… That's what made me later than we thought getting to Brest.'

'No,' came a quiet voice behind them. 'You did not "lift" it, as you put it. You took it, with the Emperor's knowledge. Hasn't it struck you yet that the excisemen seem unusually heavy sleepers tonight?'

If Vidocq had been striving for theatrical effect, he had certainly achieved his aim. Forgetting the brig, whose anchor chain could be heard running out and splashing into the sea, Marianne, Jason, Jean Ledru and even Jolival, who revived abruptly, turned with one accord to look at him. It was Jason who spoke for them all:

'With the Emperor's knowledge? What do you mean by that?'

Vidocq leaned back against the mainmast and folded his arms, his gaze going in turn to each of the tense faces turned towards him. Then, with the silky softness which his voice was able to assume when he wished it, he replied:

'I mean that he has given me my chance in these last months, and I am his loyal servant. My orders were to help you to escape at all costs. It has not been easy because, with the exception of our young friend here, everything, men and events, has been against me. But I had received my orders before you were even tried!'

For a moment, no one could say a word. They stood, rendered speechless by amazement, while their eyes struggled to take in what it was that had altered in this extraordinary man. Marianne clung to Jason's arm, still trying in vain to understand, and it was perhaps because it was beyond her power to do so that she was the first to recover her voice:

'The Emperor wanted Jason to escape? But then, why was he imprisoned, sent here…?'

'That, Madame, he will tell you himself. It is no part of my job to reveal to you reasons of State.'

'How can he tell me? You know that in a little while I shall have left France for good.'

'No.'

Marianne thought she could not have heard aright:

'What did you say?'

Vidocq looked at her and she saw a great compassion in his eyes, as he repeated, if possible still more gently than before: 'No. You are not going, Madame. Or not for the present, at least. As soon as Jason Beaufort has put to sea, I am to escort you back to Paris.'

'No! She stays with me! But it's time we had a few things explained. Just who are you?'

Gripping Marianne by the arm, Jason thrust her behind him, as though to make a shield for her of his own body. Her arms closed about him instinctively to hold him to her while he spoke to Vidocq in a voice made hard by anger. Vidocq sighed:

'You know who I am: François Vidocq and, until tonight, a convicted felon with the law on my tracks. But this escape is my last, once and for all, because I have a new life before me now.'

'A police spy! That's what you are!'

'I thank you, no! I am not a police spy. But a year ago I was given my chance, by Monsieur Henry, head of the Sureté, to work inside at tracking down crimes too sordid ever to come to light in any other way. They knew I was clever – my escapes proved that. And intelligent – my instinct for the guilty party showed that soon enough. I was working inside La Force and when you turned up it didn't need more than a glance to see that you were innocent, or one look at your file to show that it was a put-up job. The Emperor must have thought the same thing because my orders came through straightway to drop everything and concentrate on you. Further instructions followed which I adjusted to the occasion. If it hadn't been for that Quixotic gesture of yours, I should have had you away on the journey.'

'But why? What is it all about? You suffered as I did – the chain—the bagne?'

Vidocq's rather hard face lit up in a quick smile:

'I knew it was the last time, for your escape was to be mine also. No one is going to hunt for François Vidocq – or for Jason Beaufort, either. You have earned me the right to stop being an agent who works in secret, hidden behind prison bars and a convict's chains. From this moment, I belong openly to the Imperial police.[2] Everything that was done for you, was done with my approval. One of my men followed the so-called Mademoiselle de Jolival to Surcouf's house at St Malo and, before he left the town, he made known to the baron the Emperor's wish that he should take the brig Sea Witch from Morlaix roads and sail her to a spot chosen by me, but to make it look like a real theft. As you say, I suffered everything with you. Does that look like the action of a police spy?'

Jason's glance moved to Marianne who was still clinging to him. He could feel her whole body shuddering.

'No,' he said dully. 'I don't suppose I shall ever understand Napoleon's reasons, but I owe you my life, and for that I thank you from the bottom of my heart. But, what of her? Why must you take her back to Paris? I love her more—'

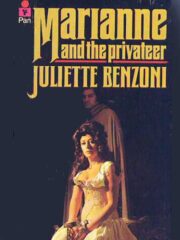

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.