Marianne was wandering in Madame le Guilvinec's wake from a stall of oysters to another heaped like a small mountain with cabbages, when she saw a cart loaded with refuse coming towards her. It was being pushed and pulled along by a group of four convicts, one of them wearing the green cap of the incorrigible criminal, under the somewhat vague eye of the guard who was following on behind in a bored way, nose in the air and hands clasped behind his back, oblivious of the sabre banging against his calves. No one took any notice of them. Convict labour was an everyday affair to the people of Brest. There were even some who smiled at them, as at old acquaintances.

The man in the green cap seemed especially well known. A ship's chandler, standing smoking his long clay pipe in the doorway of his shop, gave him a friendly wave. The convict waved back and Marianne saw suddenly that it was Vidocq. He was quite close to her by then and, drawn as though by a magnet, Marianne could not withstand the longing to attract his attention. Madame le Guilvinec had paused underneath the awning of a market gardener's stall to gossip with another old soul in a similar dolmen head-dress to her own and had temporarily forgotten her companion. Marianne raised her hand.

The convict's bright eye caught hers at once. He gave a hint of a smile to show that he had recognized her and then nodded at the next street corner where a heap of refuse was waiting to be carted away. Next, he jerked his head back to where the guard was still ambling along behind the refuse cart and tossed a pebble in his hand, as if it had been a coin. Marianne realized that he was telling her to go to the heap of rubbish where, for the price of a coin, she would be able to exchange a few words with him.

Slipping swiftly between two groups of people, without Madame le Guilvinec's seeing her, she made her way hurriedly to the corner and waited for the cart to come up with her. Then, taking a silver coin from her purse, she slipped it into the guard's hand, saying under her breath that she would like a word with the man in the green cap.

The man shrugged and uttered a crack of ribald laughter:

'That Vidocq! He's a right one for the girls, he is. Go on, then, sweetheart, but not more than a minute, mind!'

It was dark in the entrance to the alley which was no more than a narrow passage, sucking up the fog. Marianne stepped quickly inside, while the convict, with an unnerving rattle of his chains, stationed himself against the slate-hung wall, half-hidden by a small, wooden shrine adorning the corner of the house.

Still out of breath from her haste, Marianne asked: 'Have you any news?'

'Yes. I saw him this morning. He is better, but still far from well.'

'How much longer?'

'A week, at least, maybe ten days.'

'And after that?'

'After?'

'Yes… they told me he… was to suffer some punishment…'

The convict shrugged with a gesture of fatalism. 'He's certainly earned a flogging. It all depends on the man who administers it… If he goes easy with it, he'll survive.'

'But I can't – not even the thought of it! He must escape first. If not, he may be crippled – or worse!'

Quick as a snake, the convict's arm shot out from his jacket pocket and clamped down on Marianne's arm.

'Not so loud!' he growled. 'You talk of it as if it were like going to church! Don't worry, everything's in hand. Have you a vessel?'

'I shall have – or so I hope. It has not arrived yet and…'

Vidocq frowned. 'Without a boat, the thing can't be done. As soon as the alarm is given from the bagne, everyone for miles round takes up the hunt. It's worth a hundred francs to capture a man on the run… and there's a gipsy encampment right by the gates with just that one thought in mind. Real bloodhounds! The moment the gun goes off, it's out with the scythes and pitchforks and away!'

The other convicts had by now finished heaping the refuse somewhat haphazardly on to the cart and the comite's head poked round the corner:

'Ready, Vidocq… on your way, now!'

Vidocq dragged himself away from the wall and began to move out into the street:

'When your boat comes, tell Kermeur at the Girl from Jamaica. But try and make it in a week from now – ten days at the latest. So long!'

Without giving a further thought to Madame le Guilvinec, who had in any case disappeared from sight and was probably looking for her at that moment in some other part of the market, Marianne made her way back to the esplanade by the castle, eager to get back to Recouvrance at once and tell Jolival what had occurred. The street sloped steeply and the bumpy cobblestones were slippery with damp but she was almost running, Vidocq's words whirling round and round in her head: in a week – ten days at most… and Ledru had not come, might never come! They must do something – find a boat… They could not afford to wait any longer. Something must have happened to Ledru and they would have to make other arrangements…

As luck would have it, old Conan, the ferryman, was on her side of the river, sitting on a rock, smoking his pipe as placidly as if the sun were shining, and spitting from time to time into the water. Marianne was so excited that had he been on the other bank she might very well have jumped straight into the river in her haste to get across. As it was, she was in the boat before the good man had so much as noticed that he had a customer.

'Hurry!' she ordered. 'Take me across!'

The old man shrugged expressively. 'Bah!' he grunted. 'You young folks, always in a hurry. It's a wonder you take time to breathe!'

All the same, he plied his oars rather more energetically than usual and not many minutes later Marianne was scrambling out on to the rocks, tossing the man a coin as she went, and setting off homewards at a run. When she burst, panting, into the house, Jolival was standing by the table, deep in conversation with a fisherman who had just set down his basket full of fresh, steel-blue mackerel. The smell of fish mingled with that of the wood fire in the hearth.

'Arcadius!' Marianne began urgently. 'We must find a boat at once. I have seen—'

She broke off for the two men had turned and she saw that the fisherman was none other than Jean Ledru.

'A boat?' he asked in his placid voice. 'What for? Won't mine do for you?'

Feeling her legs give way beneath her, Marianne sank down on to the settle and undid her heavy cloak, which seemed to have grown suddenly too hot. Then she pushed back the linen bonnet which covered her hair and gave a sigh of relief:

'I thought you would never come – that something had happened to you!'

'No, all went well. Only I had to put in to Morlaix for a few days. One of my men was… sick.'

He hesitated slightly over this explanation but Marianne was too glad to see him to be conscious of any such detail.

'Never mind,' she said. 'You are here now. And you have your boat?'

'Yes, not far from the Madeleine tower. But I'm off again soon, back to Le Conquet.'

'You're going away?'

Jean Ledru indicated the basket of mackerel:

'I'm an ordinary fisherman, come to sell my catch. That's my only apparent motive for being in Brest. But don't worry. I shall be back tomorrow. Is everything ready, as we decided at St Malo?'

In a few words, Arcadius and Marianne told him all that had happened since she had last seen him: Jason's injury, the impossibility of his being in any condition to attempt an escape before another week was out, and the threat which hung over him as soon as he was in a way to be better which left them so small a margin of time in which to get him out. To all this, Jean Ledru listened, frowning and chewing the ends of his moustache with increasing discontent. When Marianne came to the end of her conversation with Vidocq that morning, he slammed his fist down on the table with such violence that the fish leaped on their bed of seaweed and rushes.

'You are forgetting one thing – one rather important thing. The sea. You can't treat that with impunity. The weather in a week's time will have made the Iroise impassable. Your prisoner must be aboard the vessel coming to pick him up at Le Conquet in five days at the latest.'

'What vessel is this?'

'Never you mind. The one that's to take him across the ocean, of course. It will be off Ushant in three days and it can't lie off the coast for long without the coastguard seeing it. We sail on Christmas Eve.'

Marianne and Jolival stared at each other speechlessly. Had Ledru gone mad, or had he understood not one word of all that they had told him? In the end it was Marianne who spoke first.

'Jean,' she said again, very quietly, 'we told you, a week at least before Jason will be strong enough to climb a rope or scale a wall or do any of the other things he will have to do if he is to escape.'

'I suppose he is strong enough, at least, to saw through the chain fastening him to his bed? You tell me you have managed to get all the tools he needs smuggled in to him, and money to buy himself extra food?'

'Yes, we have done all that,' Jolival said quickly. 'But it is still not enough. What would you do?'

'Carry him off, just like that. I know where the prison hospital is, the end building, almost outside the prison itself. The walls are not so high – easier to climb. I have ten men, all used to going aloft in a full gale. To get into the hospital, get your friend out and over the wall will be child's play. We simply knock out anyone who gets in our way. It'll be all over in a brace of shakes. High tide on Christmas Eve is midnight. We can sail on the turn. The Saint-Guénolé will be moored off Keravel. Besides' – he grinned briefly at the two startled faces before him, 'it'll be Christmas Eve – and the guards have their own way of celebrating. They'll be drunk as lords. We'll have no trouble from them. Any other objections?'

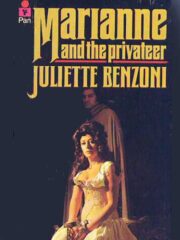

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.