'All right if I leave you here, Cap'n? If I'm to sail with the tide I must say good-bye to Marie-Jeanne. There's no knowing how long we may be away, and a man can't put to sea without a last kiss for his girl.'

The glance at Marianne which accompanied this declaration was bright with mischief. It said, as clear as day: 'You needn't worry. It's all over between us. There's another woman in my life now.' And such was Marianne's delight that she smiled beamingly on him and shook his horny hand with real goodwill. So that it was with a quiet mind on the subject of future relations between them that, with Gracchus on the box and under a steady downpour of rain which showed no signs of ever stopping, she took the road to Brest.

Ever since her arrival in that great port, Marianne had made a point of remaining as inconspicuous as possible. Gracchus had driven the chaise straight to the posting house of the Seven Saints and there they had left it. It was a hired vehicle which would return to Paris with the next traveller. Then, modestly dressed with their baggage loaded on a handcart, he and Marianne had gone down to the quay below the castle to take the ferry across to Recouvrance. This way, as Marianne had discovered when she had been staying with Nicolas, was much shorter than going round by the bridge, which meant following the Penfeld as far as the arsenal, passing close to the grim, high walls of the bagne, the convict prison, and the rope-walks.

A fisherman in the blue cap of the men of Goulven had laid aside the net he was mending to take them over in his boat. The weather that day was very nearly fine. The wind that swelled the red sails of the fishing boats heading into the Goulet and smacked in the flags that flew from the great, round towers of the castle was cold but not unduly rough. In midstream, their boatman had backed water to give way to a longboat towing-in a frigate, proud in her panoply of war, even with all her canvas stowed. The rowers, straining at their oars in time to the whistle blasts of the comite, wore the red caps and jackets of convict labourers. There were even some among them displaying with a kind of pride the green cap of the 'lifer' and all, the green caps and the red, carried the metal plate with their number on it. Marianne, seated on the rough, wooden thwart, had watched them go by with a curious sensation of horror and revulsion. The galleys might exist no longer but these men were still galley slaves of a kind and before long Jason would take his place amongst them. It had been left to Gracchus to rouse her from her gloomy reverie:

'Don't look, then, Mademoiselle Marianne,' he said. 'It'll only make you miserable.'

'Right you are there,' the boatman had agreed, setting his craft in motion once more. 'It's no sight for a young lady. But it's the chiourme does everything hereabouts. Those that aren't needed down at the docks work in the rope-walks or the sailmakers'. They collect up the garbage, too, and carry powder and cases of shot. You're for ever bumping into them. After a while, you just stop seeing them.'

Marianne thought this unlikely, even if she remained ten years in the town.

The boatman had been duly recompensed for his trouble and gave them good night, assuring them that if ever they wanted him they had only to give him a shout.

'My name is Conan,' he told them. 'Just stand on that rock there and give a hail and I'll be right over.'

Followed by Gracchus with the big trunk on his shoulder and a small boy humping a pair of carpet bags, Marianne had plunged into the stepped alleys of Recouvrance and headed in the direction of the Tour de la Motte Tanguy. More than a year had passed since she had left Brest on the mail coach but she found her way as easily as if it had been no more than a week before.

As they drew near to the tower, she was able to pick out Nicolas's little house at a glance: the whitewashed walls and granite cornerstones, the high, pointed gable window and the neat little garden, bare now of its summer flowers. Nothing had changed, not even Madame le Guilvinec from next door who for years had kept house for the secret agent without the least suspicion of his real activities.

Warned in advance by letter, the good woman came bustling out of her own house the moment Marianne and her escort had come in sight, arms spread wide and happiness written all over her long, rather masculine face, which was surmounted somewhat disconcertingly by the traditional head-dress of the women of Pont-Croix, in the shape of an erection rather resembling a kind of lace dolmen tied securely under the chin. The two women had clung together for a moment, crying a little as each remembered the sturdy figure of the man who had first brought them together.

It gave Marianne an odd feeling of homecoming to step once again into Nicolas's little house. Everything there was familiar, from the old, well-polished furniture and gleaming brass and copper to the collection of pipes and the tiny figurines of the Seven Saints which stood on a shelf, the well-thumbed books and the little wooden model of a ship which hung from a beam in the low ceiling. She settled into the house more easily even than she had done into the refurbished splendours of the Hôtel d'Asselnat and from then on, whenever the weather permitted, she had spent the best part of her time wrapped in a big, black shawl in the little leafless garden, gazing out at the roadstead and the quays along the Penfeld.

She had nothing to do but wait, now that the matter of a ship had been settled by Surcouf in his decisive fashion. She had introduced Gracchus as her servant, without denning his duties exactly, but there was little for him to do in such a small house and he passed his days exploring the town, roaming endlessly about the neighbourhood of the bagne and the poor area called Keravel which lay in a cluster of tumbledown houses and twisted alleyways between the wealthy shopping street, the rue de Siam, and the forbidding walls of the prison itself. For company, therefore, Marianne was limited to Madame le Guilvinec who would pop in for an hour or two and sit, knitting interminably, by the fire, or to the worthy woman's cat which had promptly adopted her and was more often than not to be found sleeping contentedly on the hearthstone.

Time seemed to stand still. Already it was December and even inside the Goulet the grey waters of the roadstead were rough with the great winter storms. On nights when the wind roared with the greatest violence, Madame le Guilvinec would set aside her knitting and quietly take out her beads, to pray for sailors and fishermen out at sea. Then, remembering Jean Ledru's lugger, Marianne, too, would begin to pray.

Then, one evening, as the short-lived winter sun was sinking seawards into the mist, the town became filled with a clamour so loud that it rose even above the usual noises of the port: whistles blew and there were echoes of commands roared into loud-hailers. Marianne reacted to the sounds like a war horse to the sound of the trumpet. She snatched up her great, hooded cloak and was out of the door, without even hearing the words her neighbour called after her. She sped down the narrow streets in between the tiny gardens, skidding and jumping on the stones, and reached the quay just in time to see the first wagon round the corner from the rue de Siam and turn along the quay towards the prison.

Even at that distance she could not mistake the uniforms of the guards and the long carts with their enormous wheels on which the men seemed to be crammed together more wretchedly even than at the start, but already it was getting dark and the miserable cortege was soon invisible through the skeins of mist rising from the river. Marianne shivered and, hugging her thick woollen cloak more closely about her, she turned and made her way home to wait for Arcadius, knowing that now the chain was there the Vicomte could not be far off. She had been tempted for a moment to go on as far as the Pont de Recouvrance and wait for him there by the bridge, but then she recollected that if he took the ferry, as she had done, then she would wait in vain.

He came, guided by Gracchus who had found him at the very gate of the prison, just as Madame le Guilvinec was closing the shutters and Marianne herself was bending over a stewpot suspended over the fire, gently stirring a thick and savoury-smelling soup.

'Ah, here is my uncle arrived from Paris at last, Madame le Guilvinec,' Marianne said simply, while the Breton woman fussed about the new arrival. What a long journey indeed! He must be tired!

Arcadius's face was undoubtedly drawn with fatigue, but there was something else in his expression which alerted Marianne at once. His silence, too, was disquieting. He thanked the good-hearted neighbour for her welcome, then went and seated himself on the edge of the hearth, shifting the cat to make room, and held out his hands to the fire without another word.

Marianne stood watching him anxiously, but without saying anything , while Madame le Guilvinec hurried to set the table. Gracchus stepped forward quickly:

'Never mind that, Madame. I'll do it.'

The Breton people are not talkative and they are highly sensitive to atmosphere. The widow of Pont-Croix was quick to realize that her neighbours wished to be alone and lost no time in bidding them good night, saying that she wanted to go to evening service in the chapel near by. Then, scooping up her cat as she went, she disappeared into the night. Almost before she had gone, Marianne was on her knees beside Jolival, who had let his head droop wearily on his hands.

'Arcadius! What is it? Are you ill?'

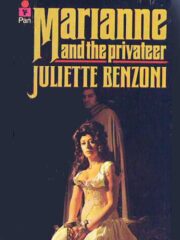

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.