'Damn fool ought to have married you in the first place, not this bowelless wench from Florida who must have been got by a wild Indian fed on crocodiles! You, now, you'd make a real sailor's wife! I saw that right away, when that old devil Fouché got you out of St Lazare.'

Marianne took this as a great compliment, and though she refrained from asking him to elaborate on the subject it was with rather more confidence that she inquired: 'So… you will help me?'

'Need you ask? A little more port?'

'Need you ask?' Marianne retorted, feeling an unexpected lightening of her heart.

The two friends drank eagerly to the success of a plan which they had yet to work out and Marianne felt a delicious sense of well-being creep over her. However, it took considerably more than three glasses of port to produce any noticeable effect on Surcouf's equilibrium. Draining his glass to the dregs, he announced his intention of escorting his visitor to the best hostelry in the town to take a little well-earned rest while he took care of the 'little matter in hand'.

'You can't stay here,' he explained, 'because I am pretty well alone in the house. My wife and children are at our house at Riancourt, near St Servan… and I can scarcely take you all the way there. Besides, Madame Surcouf is a very fine woman but I don't know if the two of you would deal together. She can be a trifle stern – and not overly tender-tongued.'

'A tartar!' Marianne decided mentally, while aloud she assured her friend that she really much preferred to go to an inn. She was anxious to pass unnoticed as far as possible and the fact that she was travelling incognito would make it awkward for her to visit his family. She might have added that she had no desire to figure as a nine days' wonder for the benefit of a pack of children, or to listen to a perfect housewife's comments on the price of grain and the difficulties of procuring foreign goods under the Blockade. A room to herself at a good inn seemed infinitely more attractive.

On this comfortable note, they parted, Surcouf confiding Marianne to the care of his man, the aged Job Goas. Job, who turned out as expected to be a retired seaman, was told off to deliver Marianne to the Auberge de la Duchesse Anne – which, besides being the best in the town, was also the regular posting house – and see her suitably accommodated. Surcouf promised to come himself later in the evening, when he had found the man they needed.

It may have been due to the intoxicating qualities of port wine or perhaps somewhat to relief at this swift acquisition of so substantial an ally, but certain it was that Marianne found the inn charming, her room all that was comfortable and the smells which wafted upstairs from the large public room very thoroughly appetizing. For the first time for very many days, life seemed to have something agreeable to offer.

The little town lay snug within its walls but outside the wind was howling with redoubled fury. The night promised to be a stormy one and the riding lights on the tall masts in the harbour were bobbing up and down like so many drunken sailors. In Marianne's room, however, protected by thick walls and thick panes of leaded glass in the windows, all was warmth and safety. The bed, with its piled-up mattresses surmounted by an enormous red eiderdown, smelled pleasantly of linen dried in the sun, spread on the juniper bushes out on the open heath. Tired from her long journey in bad weather, Marianne could have gone straight to bed, but the port and ginger biscuits had given her an appetite. She felt ravenously hungry and her hunger was sharpened by the delicious cooking smells which were seeping through the whole building. Besides, Surcouf had advised her to eat her dinner in the public room so that he would not have to be taken to her bedchamber when he came with the man he had gone to find. The inn itself was a highly respectable one where a lady might eat alone without fear of importunities. Nevertheless, Marianne decided that Gracchus should share her dinner, so as to be on hand in the event of unlikely but still possible trouble while she waited for Surcouf and his friend.

Seated at a small table close to the immense hearth at which a woman in the graceful lace hennin worn by the women of Pléneuf was making pancakes with the aid of a long-handled pan, the Princess Sant'Anna and her coachman applied themselves unashamedly to the enjoyment of Cancale oysters, large crabs of the kind known as 'sleepers' served with salted butter and a vast cotriade, the Breton bouillabaisse, pungent with herbs. They ended the meal with the traditional golden pancakes and sparkling cider.

Marianne and Gracchus were sipping their fragrant coffee while all around them pipes were being filled with the fine tobacco of Porto Rico, when the low door flew open at a vigorous push from Surcouf. His entrance was the signal for a chorus of loud and joyful greetings, but Marianne paid no attention to these. All her senses were trained on the man who entered in the privateer's wake. Most of his face was hidden by the upturned collar of his heavy pilot coat, but Marianne knew that face too well to be mistaken in its owner, even if he had been wearing a false beard and a hat pulled over his eyes, which he was not. The 'man they needed' was Jean Ledru.

CHAPTER TWELVE

The Ninth Star

In the little house which had belonged to Nicolas Mallerousse, Marianne settled down to begin her vigil. She was waiting for two things. The first of these was the convict chain which should by this time be nearing the end of the journey begun more than three weeks before. The second was Jean Ledru's lugger, the Saint-Guénolé, which was working her way round the coast from St Malo to lie up in the little port of Le Conquet until it was time to move out into Brest roadstead.

Despite the bad weather, Ledru had put to sea with a crew of ten able-bodied seamen on the same morning as Surcouf had handed Marianne into her chaise and sent her on her way with boisterous good wishes.

The previous night, when Jean Ledru had reappeared in her life, Marianne had hesitated for a moment before committing Jason's future to the very person to whom she owed her own first, highly unenjoyable sexual experience, as well as subsequent trials of a very different kind. Surcouf, seeing Marianne's troubled face, had uttered a shout of laughter and given Ledru a cheerful push in her direction:

'He came to me last March, along with a personal letter from the Emperor asking me to take him back. To please you. So between the pair of us we patched things up – and have not ceased to be grateful to you. That Spanish war was no good for Jean. He did well enough, but he's not at home on shore. And I was happy to have a good seaman back.'

Feeling deeply conscious of the explosive nature of their earlier relations, Marianne extended her hand to her one-time comrade in misfortune: 'How do you do, Jean. I am glad to see you again.'

He had taken the proffered hand, unsmiling. The eyes that were like two blue forget-me-nots beneath lashes bleached white by the sea, remained thoughtful in the face whose tanned skin and short fair beard were still as she remembered, and for an instant Marianne was in doubt of his reaction. Was he still angry with her? Then, quite suddenly, the still face came to life and the gap between beard and moustache widened into a candid smile:

'And I'm glad too! I should rather think so after what you did for me – and if I can repay it…'

It was all right then. Everything was going to be all right! After that, she had tried to warn him of the risks involved in trying to outwit the law of the Empire but, like Surcouf, he would hear none of it.

'The man we have to rescue is a sailor and Monsieur Surcouf says he's innocent. That's enough for me. I don't want to know any more. What we have to do now is decide how to go about it.'

For two long hours, the three men and the girl sat round the table with a pot of coffee and a pile of pancakes in front of them, working out the broad outline of their plan. It was an audacious one but although Marianne's green eyes were occasionally shadowed with doubt, in the three pairs of blue ones belonging to the three men there was never anything but blazing enthusiasm and the thrill of adventure, so infectious that she soon abandoned every objection, except for one final one when the question of the lugger Saint-Guénolé was raised.

'But surely, these luggers are small boats, too small to sail all the way to America? Don't you think a larger vessel—'

She had repeated her proposal, which Surcouf had already turned down with magnificent disdain, to purchase a ship; but once again the corsair king explained to her, quite kindly, that she was talking nonsense.

'This is the ideal type of vessel to pass unnoticed, and to get someone out of Brest in a hurry, especially in the tricky waters of the Fromveur and the Iroise. She holds well in a sea-way and sails close to the wind. Leave what comes after that to me. And don't worry. There'll be a ship for America when it's wanted.'

With this, Marianne was obliged to be content and they parted for the night. All the time they had been talking, Marianne had been observing Jean Ledru, trying to discover from his inexpressive face whether or not he was cured at last of the destructive and ill-fated passion he had felt for her. His face had told her nothing but, just before they parted, he had told her himself, with a little teasing smile on his lips. Rising to put on his pilot jacket he had spoken, ostensibly to Surcouf, but really for the girl's benefit:

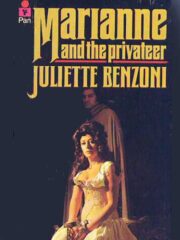

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.