All these things were in her mind as the horses trotted easily towards the next stage. The day was as grey as ever, but the rain had stopped. As ill luck would have it, its stopping had been the signal for a sharp wind to get up which must have been unpleasant for men out in the open in wet clothes. A hundred times, as they went on, Marianne looked back to see if the chain were yet in sight, but it never was. Even at their present gentle pace, the carriage could outstrip the lumbering wagons with ease.

Just as Jolival had predicted, they reached Saint-Cyr far in advance of the convict chain, giving him time to engage rooms for Marianne and himself in a modest but respectable inn. Even this necessitated a certain amount of argument, since her first concern was to discover where the prisoners were to spend the night. She was directed to a huge barn just outside the town, whereupon she immediately rejected the inn, declaring she could perfectly well sleep in the chaise, or even in an open field. For once, Arcadius lost his temper with her:

'What are you trying to do? Catch your death of cold? That will be a fine help, if we are obliged to put up in some inn for a week to nurse you!'

'Of course I should not stay anywhere – not if I were shivering with ague! If I were at my dying gasp I should still go with him, on foot if I had to!'

'Much good that would do you, if I may say so!' Jolival growled. 'For God's sake, Marianne, stop playing off these tragedy airs! It will not help Jason Beaufort if you catch your death on this damned road. On the contrary. And if your only aim is to mortify your flesh so as to share his sufferings, then you had better shut yourself up in a convent, my dear, the strictest we can find, where you may fast and sleep on the floor and have yourself beaten three times daily if you please! At least you will not be a hindrance when the chance of an escape does arise!'

'Arcadius!' Marianne cried, shaken. 'To talk to me so!'

'I talk to you as you deserve. And, since you will have it, I think this insistence of yours on following the chain is foolish beyond permission!'

'I have told you a hundred times: I cannot be apart from him. If anything were to happen to him—'

'I should be here to see it. You would be a hundred times more useful to us posting on to Brest and settling down in the house you have inherited, establishing yourself in the neighbourhood and getting to know the people. Have you forgotten that we are going to need assistance, a sea-going vessel and a crew? No, you prefer to stay here, weeping at the foot of the Cross! Trailing in the wake of the chain, like some self-dramatizing Magdalen! Or are you going to whip out a veil and mop his fevered brow, like St Veronica? Confound it all, if there had been the slightest chance of saving Jesus, I promise you those women wouldn't have wasted their time trotting about the back streets of Jerusalem! Are you determined the Emperor should hear that you have been defying his commands again? That the Princess Sant'Anna is following the convict chain to Brest?'

'He will not know. We are travelling very quietly. I pass for your niece.'

This was true. For greater safety, Jolival had procured, through Talleyrand, a passport in his own name, including a mention that his niece Marie was travelling with him. But the Vicomte only shrugged irritably:

'And do you think no one will know your face? You little fool, the guards with the column will have found you out within three days! So no dramas, if you please. Do nothing to make yourself conspicuous. Like it or not, you will go to bed like other people – at an inn!'

Overborne, but resentful, Marianne gave in at last, with the stipulation that she need not retire to her inn until the convict chain had halted for the night. She could not bear to give up a single chance of seeing Jason.

'No one will even notice me,' she pleaded. 'There are so many people waiting there already.'

Once again, she spoke the truth. The dates on which the chain came through were always the same and they were known throughout the district. It had a curious fascination for the country people and they would come, often from miles around, to gather at the places where the wagons halted and sometimes to follow them for part of the way. Some came with charitable intentions, giving the prisoners little gifts of food, or a worn garment, or a few small coins. But for the most part, they came simply for amusement, honest folk finding a powerful relief from their own humdrum troubles in contemplation of the criminals' punishment, and of a wretchedness beyond anything even the poorest there would ever know.

The little town was full of people, although the sharpest, and the better informed, had already taken up their positions near the barn. The fact was that before they were allowed to rest for the night the convicts had to submit to a thorough, detailed search, intended to simplify the task of the guards during the remainder of the journey. At the other halts, there would be nothing more than a check on the shackles and a brief run-over. Marianne wormed her way through the crowd, Jolival, still disapproving, on her heels.

They heard the chain coming long before they saw it. Borne on the wind came a fearsome clangour of voices howling and loud, raucous singing, made louder as it approached Saint-Cyr by the roaring of the worthy townsfolk. Then, just passing the last houses of the town, two mounted officers appeared, their shoulder belts showing up as a white cross on each chest. They stared straight ahead, grim-faced, whereas the prison guards who came after them were grinning at the crowd, like the heroes of a successful play. Behind them, the first wagon lumbered into view.

When all five vehicles had been lined up together in a field, the prisoners were made to get down and the search began. At the same moment, as if in response to some secret signal, the rain came on again.

'Are you really determined to remain here?' Jolival murmured into Marianne's ear. 'I warn you, it is no fit sight for you. You should—'

'Once and for all, Arcadius, I ask you to let me alone. I want to see what they do to him.'

'As you will. You shall see. But don't say I didn't warn you.'

Marianne turned away from him pettishly. A few moments more found her staring very hard at the ground, scarlet with shame. Despite the cold and the rain, the prisoners were being made to strip off every vestige of clothing. Standing there, barefoot in the mud, in nothing but the iron collars round their necks, they were subjected by their guards to a search so thoroughly degrading that it could only have been intended as an additional punishment. While one man inspected suits, shoes and stockings, another examined every orifice of their bodies with minutest care. It was a known fact, however, that the prisoners were adept at concealing a variety of tools, from tiny files to watchsprings which could release a man from his irons in less than three hours.

Marianne, crimson to the roots of her hair, kept her eyes firmly on her own feet and on the clump of trampled grass on which she stood. To everyone around her it seemed to be a high jest. Even the women, honest matrons for the most part, were commenting on the prisoners' persons with a freedom which would not have disgraced a grenadier. Desperate, Marianne tried to turn and beg Jolival to take her away, but a sudden movement among the now wildly excited crowd parted her from him and, without quite knowing how, she found herself carried into the front rank of the onlookers. The hood which she had drawn down over her hair to hide her face had been pushed back in the press and suddenly she saw Jason right in front of her.

The distance between them was not so great that he could help but see her. She saw his face change horribly. His skin turned suddenly grey and the look of anger and shame glaring in his eyes was frightening. He thrust at her violently to drive her away, oblivious of the whip which at that instant thudded into his back.

'Go away! Go away at once!'

Marianne tried to answer, to tell him that she had only wanted to share his sufferings, but already there was an iron hand gripping her arm, dragging her back, irresistibly, regardless of the pain it caused her. There was a moment's agonizing pressure, a quick scuffle and Marianne found herself at the back of the shouting wedge of people staring into the face of Jolival, who was literally green with anger:

'Well? Are you satisfied? You saw him? And you made damned sure that he saw you – at the moment of all moments when he would a hundred times rather have died than be seen by you! Is this what you call sharing his ordeal? Don't you think he has enough to bear?'

Marianne's overstretched nerves snapped all at once and she burst into convulsive sobs:

'I didn't know, Arcadius! I couldn't ever have known, ever imagined anything so vile! I was pushed forward by the crowd – when I only wanted not to look…'

'I warned you,' Jolival said ruthlessly. 'But you are worse than a mule! You will not listen to anyone! One would think you took pleasure in torturing yourself.'

Marianne's only answer was to cast herself into his arms in such desperate floods of tears that he was softened. His hand came up to stroke her rain-sodden hair.

'There, there… Hush, now, my baby! I am sorry I was angry – but you make me so when you insist on adding to your own troubles.'

'I know… dear friend… I know! Oh, I am so ashamed!… You can't know how ashamed I am! I have hurt him… I wounded him, when I would give my life…'

'Now, now – don't begin again!' Jolival besought her, gently removing her clinging form from about his neck. 'I know all about it, always have done, and if you do not calm yourself at once and stop turning the knife in the wound, I swear to you on my honour I will box your ears as if you were my own daughter! Come, now, let us go back to the inn.'

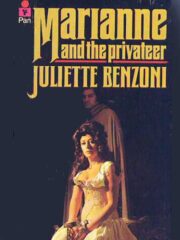

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.