Jolival gazed with a jaundiced eye at the desolate scene about him. Here and there in the waste an occasional chimney was beginning to smoke. On the edge of the crowd a number of dark figures stood in isolated groups of two or three, with the wretched, hopeless air of people in great grief. They were the wives, relatives and friends of those about to be deported. Some were weeping, others simply stood, like Marianne herself, faces strained towards the hospice, eyes wide open, every feature turned to stone by the hard frost of unshed tears.

There came a sudden roar from the crowd. Creaking, grinding, the great gates were swinging open… Two mounted officers appeared, their bodies hunched against the rain which streamed from the angles of their cocked hats, using their horses and the flat of their swords to beat back the crowd, which was already surging forwards. A shudder ran through Marianne. She took a step forward, but instantly Jolival seized her arm and dragged her back.

'Stay where you are!' he said, with unconscious harshness. 'You need not go any closer. They will pass us here.'

The first wagon had already appeared, to be greeted by a horrid outburst of boos, catcalls and abuse. It was a kind of long cart, supported on two enormous iron-shod wheels and divided along the whole of its length by a two-sided wooden bench on which the prisoners sat back-to-back, twelve to a side, their legs dangling, held in place by a crude rail at waist level. Each man was chained by the neck by means of a solid, three-cornered iron collar attached to a length of chain, too short to allow him to jump from the wagon on to the road. This chain was in turn connected to the much heavier chain which ran the length of the bench, its end lying firmly beneath the foot of the armed guard standing at the end of each wagon.

There were five of these conveyances. There was no protection, not even the most rudimentary piece of sacking, to stand between the prisoners and the rain which was already soaking through their clothes. Their prison uniform of black and grey striped canvas overalls had been taken off them for the journey and their own clothes restored to them, but so mutilated that should any man escape no one who saw him could doubt that he was a convict. Coats were lacking their collars, cuffs were shredded to ribbons, and hats, for those that had them, had been shorn of their brims.

Marianne watched them pass, appalled at the pallid, unshaven faces, hate-filled eyes and open mouths that spewed out blasphemies and obscene songs. They were shivering in the icy rain and some, the youngest, had to bite back tears when in a grieving face that loomed up through the grey drizzle they recognized the features of someone they knew.

In the leading wagon, she caught sight of François Vidocq. He sat wrapped in a scornful silence which in the midst of the cursing and groaning all about him had its own kind of greatness. The eyes that rested on the excited mob held such contempt that they seemed not to see at all, yet they saw Marianne and were instantly transformed. She saw the stubbly jaw relax in a brief smile as Vidocq nodded to the wagon next in line. At the same time, Jolival tightened his hold on Marianne's arm.

'There!' he hissed. 'Fourth from the front.'

But Marianne had already seen Jason. He was sitting very upright among the rest, his eyes half-closed, his mouth set in a thin line. He was quite silent, his arms folded on his chest, and seemed wholly insensible to all that was going on around him. His attitude was that of a man refusing either to see or to hear, his being turned inwards the better to conserve his strength and energy. The rags of his torn cambric shirt and the ripped, collarless coat gave little protection to his broad shoulders and the tanned skin showed through in many places, but he did not appear conscious of the cold or the rain. In the midst of this howling mob, with fists raised in impotent menace, mouths distorted by foul invective, he was as remote as a figure carved in stone. Marianne, her lips already parted to call out his name, fell silent when he passed her unseeingly, realizing quite suddenly that it might only have caused him pain to see her there in the crowd.

One cry of horror she could not repress, when the guards, tiring of the racket kept up by their prisoners, took out their long whips and laid about them impartially, flailing at cringing backs and shoulders, and at the heads they tried to shield with their folded arms. The shouting ceased and the cart rolled on.

'Bastards! Stinking bastards, knockin' about a right'un like him!' muttered an angry voice behind her. Marianne knew the voice and, turning, saw Gracchus, whom she and Arcadius had left with the chaise in the square of Gentilly village, standing bareheaded in the rain with clenched fists and great tears rolling down his cheeks, mingling with the rainwater. He must have left the carriage to take care of itself and come himself to see the chain pass by. His eyes followed Jason's cart until it was out of sight. Then, when it had been swallowed up in the mist, and the other carts had come and gone and the kitchen wagon was clattering by with a great clanging of metal pots and pans, Gracchus looked at his mistress, who was sobbing on Jolival's shoulder.

'We're never goin' to leave him like that?' he asked belligerently.

'You know quite well we're not,' Jolival told him. 'We are going after him and we are going to do our best to free him.'

'Then what are we waiting for? Beggin' your pardon, Mademoiselle Marianne, but you'll not get him out of it by crying. We've got work to do! Where's the first stop?'

'Saint-Cyr.' It was Arcadius who answered. 'That's where the last search is made.'

'We'll be there first. Come on!'

The discreet travelling carriage, with no outward signs of wealth beyond a pair of lively-looking post horses, was waiting with lighted lamps under the trees not far from the Pont de la Bièvre. As the morning advanced, the tanneries which bordered this stretch of the river began to come to life, spreading a powerful stench through what was otherwise a pretty scene, dominated by the square church tower. Marianne and Jolival got into the chaise in silence while Gracchus hoisted himself nimbly on to the box. A click of the tongue as the whip curved gracefully through the air to flick the leader's ear, a faint creak from the axles and they were off. The long journey to Brest had begun.

Marianne leaned her cheek against the rough fabric of the squabs and abandoned herself to her tears. She wept quite silently, with no sobbing, and it did her good. It was as if the hideous sights she had just beheld were being washed from her eyes, and at the same time her own natural courage and will to succeed slowly returned to take possession of her mind. Arcadius, sitting beside her, knew her too well to make any attempt to stem the beneficent flow or offer the least word of comfort. What could he have said? It was necessary for Jason to endure this dreadful journey because it led not to his prison alone, but to the sea, from which he had always drawn his strength.

Marianne left Paris without regret, with no expectation of ever going back there, or with no more regret than the slight pang she felt at parting from her few remaining friends there: Talleyrand, the Crawfurds and, most of all, her dearest Fortunée Hamelin. But Fortunée had refused to give way to sentiment. Even as she embraced her friend for the last time, her eyes full of tears, she had insisted, with all the infectious enthusiasm of her sun-loving nature:

'This is not good-bye, Marianne! When you are an American, I shall come and visit you there, and see if the men are as handsome as they say. Judging by your corsair, it must be true!'

Talleyrand had confined himself to a calm assurance that they were bound to meet again some day, somewhere in this wide world.

Eleonora Crawfurd had applauded Marianne's plan to put the width of the ocean between herself and her alarming husband. Adelaide, left to act as mistress of the family mansion, had treated their parting in a philosophical fashion. As far as she herself was concerned, there was little to fear however matters turned out. If Marianne failed in her plans for Jason's escape, then she would of course return to her own place in the household. If she succeeded and she and Jason won their way to the State of Carolina, then there would remain nothing for Adelaide to do but pack up her traps, slip the key under the door and catch the first boat to a new and adventurous life, with the idea of which she was already half in love. All was therefore for the best in the best of all possible worlds!

Before she left Paris, moreover, Marianne had received a communication from her lawyer which, in the circumstances, was extraordinarily welcome. It stated that the unfortunate Nicolas Mallerousse had, during the time when she had stayed with him in Brest, after her escape from Morvan's manor house, constituted her his sole heir. The little house at Recouvrance and the few bits and pieces it contained were henceforth her own property, 'in memory', Nicolas had written in his will, 'of the days when she had made me feel as if I had a daughter once again'.

This legacy had touched Marianne deeply. It was as though her old friend were speaking to her from beyond the grave, assuring her of his affection still. She also saw in it the hand of Providence and something very like tacit approval on the part of fate for what she meant to do. There was, in fact, nothing which could possibly have been more useful just then than the little house on the hill, looking out one way to the sea and the other to the buildings of the arsenal and, in the midst of them, the prison.

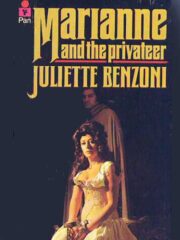

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.