All the same, when the spires of Paris appeared at last through the autumnal mists she very nearly shouted for joy and when the wagon reached the village of La Villette and crossed over the site of the unfinished canal of St Denis she had to stop herself jumping down from her seat and running ahead, but she knew it was best to keep up the pretence to the end.

The powerful smell emanating from the city's refuse dump, near which they were obliged to pass, seemed to jerk the driver out of his doze. He opened first one eye, then the second, then turned his head to look at Marianne, but so slowly that Marianne wondered if he were animated by some form of very slow clockwork.

'Tha coozen t'laundress,' he asked 'wheer dost a live? T'mester said t'set thee doon reet by, but ahm f't'market.'

Marianne had had plenty of time on that endless drive to think about what she meant to do when she eventually reached Paris. A return to Crawfurd's house was out of the question and it could prove equally perilous to make for her own. At this point it had occurred to her that by now Fortunée Hamelin might have returned home from Aix-la-Chapelle. The summer season there was over, surely she would be back in her beloved Paris… unless she had sacrificed that love in favour of her other ruling passion for Casimir de Montrond who was officially under open arrest in the Flemish town of Anvers. If that proved to be the case, Marianne decided, she would wait until it was quite dark and then try and slip quietly into her own house in the rue de Lille. So she answered the man: 'She lives quite near the Barrière des Porcherons.' The yokel's dull eye brightened fleetingly: 'T'beant mooch aht't'road. Ah'll set thee doon thar than.' Upon which decisive utterance he appeared to fall asleep again, while ahead of them, by the side of a broad expanse of fresh water, there loomed up Ledoux's elegant rotunda and the guingettes with their red trellises of the Barrière de la Villette.

Safe in her disguise, Marianne did not flinch when the guards made their routine check. Then they were off again, following the wall of the Fermiers Généraux as far as the Barrière de la Chapelle, after which the wagon turned into the Faubourg St Denis. When Marianne's destination was reached they parted without a word spoken and she set out, shaking uncontrollably with the excitement of finding herself in Paris once more, to run to the rue de la Tour d'Auvergne as if her very life depended on it.

It was something of an ordeal because the streets led steeply uphill all the way to the village of Montmartre. To make running easier she had taken off the heavy sabots, which were too big for her and chafed her unaccustomed feet. Consequently, by the time she came to the white house which always in the past offered her such a warm welcome, she was barefoot, red-faced, tousled and panting, but her only fear was that she might find the shutters closed and the house wearing the dismal, unfriendly look common to all houses when the people who live there are away. No, the shutters were open, the chimneys smoking and a vase of flowers could be seen through the hall window.

But when Marianne entered the gate and made to cross the courtyard to the front door, she saw the gatekeeper come running out after her as fast as a pair of very short legs would carry him, holding his arms out wide as if to block her path. With a sinking heart she saw that he was a new man, one she had not seen before.

'Here! You there, girl! Where d'you think you're going?'

Marianne stopped and waited for him, so that he all but cannoned into her.

'To see Madame Hamelin,' she said coolly. 'She is expecting me.'

'Madame does not receive persons of your kind. Besides, she's not at home. Be off with you!'

He was pulling at her arm, trying to drag her away but Marianne shook him off:

'If she is not at home, then fetch Jonas to me. I suppose he is at home?'

'Fetch him to such a hussy as you? Tell me what name I should say if you want me to go, then.'

Marianne hesitated fractionally, but Jonas was a friend and he was used to seeing her in unexpected guises:

'Say: Mademoiselle Marianne.'

'Marianne what?'

'Never you mind. Go and bring him to me at once and take care Jonas is not angry with you for keeping me waiting.'

The gatekeeper departed unwillingly for the house, mumbling under his breath as he went various uncomplimentary things about brazen hussies forcing their way into honest folks' houses. Not many seconds later, Jonas, Fortunée's major-domo, literally burst out of the glazed front door, his good-humoured black face split in two by an enormous smile of welcome:

'Mademoiselle Ma'anne! Mademoiselle Ma'anne! It is you!… Come you inside dis minute! My lord, but what you doin' dressed like dat?'

Marianne laughed, feeling her spirits revive miraculously at the warmth of this familiar welcome. Here, at last, she had found a safe harbour.

'Poor Jonas! Nine times out of ten I seem to arrive on the doorstep looking like a complete ragamuffin. Madame is out?'

'Yes, but she's coming back soon. You come inside and rest yourself while you wait.'

Dismissing the gatekeeper with an imperious wave of his hand, Jonas led Marianne straight into the house, telling her as they went of the anxiety his mistress had been in on her account since her return from Aix.

'She thinks you' dead! When Monseigneur de Benevento tell her you disappeared, I thought she would run mad, I give you my word… Listen! Here she comes now.'

In fact, hardly had Jonas shut the door before Fortunée's brougham entered the courtyard, described a perfect circle round the fountain and drew up at the foot of the steps. Fortunée got out but she looked very grave and Marianne saw that for the first time since she had known her, her friend was dressed in a plain walking dress of a severe dark purple colour. Also unusual for her was an almost total absence of paint on her face and as her veil was drawn up, Marianne could see by her red eyes that she had been crying. But already Jonas had hurried out to her, calling:

'Madame Fortunée! Mademoiselle Ma'anne is here! See!'

Madame Hamelin looked up and a light of joy sprang into her lack-lustre eyes. Without a word she ran up the steps and flung herself into her friend's arms, hugging her and crying at the same time. Marianne had never seen the light-hearted Creole in such a state and while she returned the embrace with equal fervour she pleaded in an undertone:

'Fortunée, for God's sake, tell me what is the matter! Were you truly so afraid for me?'

Fortunée freed herself quickly and stood for a moment holding Marianne at arms' length, her hands resting on the girl's shoulders while she gazed deep into her eyes with such an expression of compassion that a cold trickle of fear ran through Marianne's veins, leaving her unable to speak.

'Marianne, I have just come from the court,' Madame Hamelin said at last in the gentlest possible voice. 'It is all over.'

'What – what do you mean?'

'Jason Beaufort was sentenced to death an hour ago.'

Marianne staggered as if she had been shot. But after so many days' unconscious expectation of this very thing, she was to some extent prepared, without knowing it, so that the wound had begun to heal over almost as soon as it was made. She had known in her heart that one day she would have to listen to those dreadful words and, as the human body prepares secretly to fight for life against the disease it harbours, so her mind had armed itself against the suffering to come. The danger was too close now, there was no time for weakness, no time for tears or terror.

Fortunée had extended her arms in an automatic gesture, expecting Marianne to fall down in a faint, but she let them drop slowly to her sides as she stared in amazement at the unknown woman who looked back at her out of a face which had turned suddenly to stone. Marianne spoke in a voice of ice:

'Where is the Emperor? At St Cloud?'

'No. The whole court is at Fontainebleau, for the hunting. What are you going to do? You won't—'

'Oh yes I shall. That is precisely what I shall do. Do you think I care for anything in this world if Jason is not in it? I swore by my mother's memory that if they killed him I should stab myself at the foot of the scaffold. What are Napoleon's rages to me? He shall listen to me, whether he likes it or not, whether it suits him or not! Afterwards, he may do to me what he likes. As if it mattered!'

'Don't say that!' Fortunée begged her, crossing herself hurriedly, as if to avert an evil fate. 'Think of all of us who love you.'

'I am thinking of the man I love, and without whom I will not live! There is only one thing I ask of you, Fortunée. Lend me a chaise and some clothes, and a little money, and tell me where I can go in Fontainebleau to avoid being arrested before I have seen the Emperor. You know the place, I think. If you will do this for me, I will bless you to my dying day—'

'Stop!' Fortunée cried distractedly. 'Will you stop talking about dying! Lend you money, my chaise – what are you thinking of?'

'Fortunée!' Marianne protested in accents of hurt surprise, but before she could say more her friend's arm was folded lovingly about her waist and Fortunée was leading her upstairs, murmuring affectionately in her ear:

'We'll go together, of course, you silly thing. I have a house there, a little retreat of my own by the river, and I know every inch of the forest. We'll find that useful if you don't succeed in getting into the chateau – much as Napoleon hates to have his hunting interrupted. But if that is the only way…'

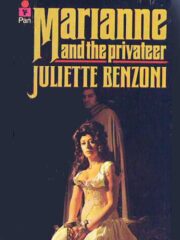

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.