'No, not good-bye… or only for a little while! I shall come again and—'

'No. I forbid you to. It would not be wise. You are forgetting that you yourself are watched. I must know that you are safe, at least.'

'Don't you want to see me again?' Marianne was almost in tears.

He kissed the tip of her nose lightly, then her eyes and then her lips.

'Silly! I have only to close my eyes to see you. You will never leave me. But I must be wise for two – and now, especially, when your life may be at stake.'

'Only four minutes!' The turnkey's head appeared round the door, looking anxious. 'You'll have to hurry, lady.'

With one last kiss, Marianne tore herself bravely from Jason's side. She was half out of the door when Vidocq caught her arm and spoke to her softly:

'Do you know the Persian poets?'

'N-no, but—'

'One of them has written: "Never lose hope, even in the midst of disaster, for the toughest bone contains the sweetest marrow." Go now.'

She glanced up at him uncertainly before, blowing one last kiss to Jason, she hurried out to join Ducatel who was pacing up and down outside like a caged bear.

'Hurry!' he told her, shutting the door swiftly. 'We've got no more than three minutes! Here, take my hand. We'll have to run for it.'

They raced together for the stairs while from the passages behind them the measured tread of the watchmen on their rounds was already making itself heard. At the same time, at the clatter of heavy, nailed boots, the whole prison seemed to come awake. Oaths, curses and ugly shouts rang out on all sides until it seemed as if each door concealed its own miniature version of hell. The smell which even in Jason's cell had been unpleasant, became frankly unendurable as they passed certain doors and when they emerged at last into the Cour du Greffe Marianne found herself taking in great gulps of fresh air. They had resumed a normal walking pace by now and the keeper remarked as he let go Marianne's hand:

'I dare say a little glass of something wouldn't do either of us any harm, my lady. You looked like a sheet when you came out, and I can't say I feel so hot myself, after that close shave.'

'I'm sorry. But tell me, this man François Vidocq, is he indeed an escaped convict?'

'I'll say he is. The guards can watch him for all they're worth, but they can never keep a hold on him. Every time he slips through their fingers. But he can't keep out of trouble, seemingly. He always comes trotting back again. But don't get me wrong. He's not one of your real desperate ruffians. He's not killed anyone. So back they sends him again to serve his time – Toulon, Rochefort, Brest, he knows them all. They're all the same to him. Just the same this time, it'll be. They'll pack him away, and after a bit he'll be off out of it again as usual. And then the whole round will begin again, until one day one of his guards has had enough and quietly puts him away. And that'll be a pity, because he's not a bad lad…'

But Marianne was no longer listening. She was pondering in her heart the words this strange prisoner had said to her. He had mentioned hope, and hope was the one word she had needed to hear, since Jason had not uttered it. More, he seemed resigned, almost indifferent, accepting with what seemed to her a terrifying calmness the possibility of dying for his country's service.

'He shall not die,' she vowed inwardly. 'I shall not let them kill him and he shall not die! Even if his judges condemn him, I will make the Emperor listen to me and he will have to grant me his life…'

That was the one thing that mattered. Even if life meant a slow death in penal servitude. Until that day she had always thought of it as a kind of foretaste of hell from which no one ever emerged alive. But this man Vidocq was living proof that it was not so. And she knew that while Jason lived she, Marianne, would devote every moment of her life to saving him from the undeserved penalty awaiting him. Gathering together all her strength, she thrust away her fears, her anguish and all thoughts of farewell. Every atom of her being belonged to Jason Beaufort but she believed too that Jason Beaufort belonged henceforth to her and her alone. And because of this she felt a greater strength and fighting spirit than she had ever known before, even on the night when, sword in hand, she had challenged Francis Cranmere to answer for the slur on her honour. The fire of the ancient blood of Auvergne and the unrelenting tenacity of her English descent united in her to produce all the warlike qualities of those other women from whose line she came who had studded history with their loves, their passions and their vengeances: Agnes de Ventadour who had turned Crusader to be revenged on a faithless lover, Catherine de Montsalvy who had risked death a hundred times for the husband she loved, Isabelle de Montsalvy, her daughter, who had fought her way to happiness through the horrors of the Wars of the Roses, Lucrèce de Gadagne, wielding a sword like a man to win back her castle of Tournoel, Sidonia d'Asselnat who had fought like a man yet loved like ten women during the Fronde, and so many more. Go back as far as she would in the annals of her family, Marianne would find the same story, the same pattern of war and arms, of blood and love. Only fate might change the course of human life, but as she followed the keeper down the damp passage leading to his lodging, Marianne knew that she had at last accepted the crushing weight of that heritage, owned herself daughter and sister to all these women because now she had found her own cause for which to fight and to live. And so, she felt no sadness or grief but rather a sense of happiness and exultation and triumph, drawn from the hour which had just passed, but most of all a vast, inner peace. Everything was suddenly so simple. Henceforth, she and Jason were one heart and one flesh. If one died, then the other would die too… and that would be the end.

As she left the prison, she thanked the keeper warmly and slid into his hand a number of gold coins which brought the blood rushing into his cheeks. Then, slipping back into her part of the country girl elated by a good supper and a drop of wine, she hung on Crawfurd's arm as they set out on the short walk to the church of St Paul where the Scotsman had told the cab driver to wait for them, rather than attract attention by lingering outside the prison. The sentry called out a jovial good night to them as they moved slowly away, walking carefully to avoid tripping on the uneven cobbles.

'You're happy, I can tell,' Crawfurd said softly as they turned into the rue St-Antoine. 'Am I right?'

'Yes. It's quite true, I am happy. Not that Jason gave me much encouragement to hope. He expects to be found guilty and, worst of all, he seems to be resigned to it, because the good of his country demands it.'

'That does not surprise me. These Americans are like their own splendid country: simple and big. Pray God they may never change! All the same, he may be resigned, but that is no reason for us all to be so – eh? As our friend Talleyrand would say.'

'I agree. But I wanted to tell you—'

However, Quintin Crawfurd was not destined to hear what Marianne wanted to tell him of her gratitude, because as they approached the little group of elm trees in the miniature square in front of the old Jesuit church, the Scotsman suddenly pressed the arm which lay within his.

'Sssh!' he said… There is something there…'

A light wind had got up, sending the heavy rain clouds scudding across the sky, veiling the moon so that it shone through only as a pale, diffused glow. Against this faint lightening of the darkness, the trees in front of them seemed to have taken on strange, moving shapes, as if men in billowing cloaks might be concealed behind them. The square shape of the cab was clearly to be seen near the church but the driver was not on the box. A whinny made Marianne glance to her right and she made out several horses standing in a side alley. It needed no words, nor the movement made by Crawfurd drawing the hidden pistol very slowly from the inner pocket of his cloak, to make Marianne suspect a trap, but she had no time to wonder any more.

There was a sudden movement, as if the trees had come to life, and in a twinkling the two on foot found themselves the centre of a menacing circle of black, silent shapes of men dressed in full capes and broad-brimmed hats. Crawfurd presented his pistol:

'What do you want? If you mean to rob us, we have no money onus.'

'Put up your weapon, Señor,' said one of the shadowy figures, speaking in a strong Spanish accent. 'We have more powerful ones trained on you. It is not gold that we are after.'

'Then what do you want?'

But the Spaniard, whose face was invisible beneath his wide hat, disregarded the question, and at a sign from him the Scotsman found himself expertly gagged and bound. Then the man turned to the figure at his side:

'That is the one?'

The person addressed, who was much shorter and slighter than the first speaker, moved a step or two closer and, taking a dark lantern from beneath the enveloping cloak, opened the shutter and held it up so that the light shone on Marianne's face. At the same time, the light fell on the cloaked figure and revealed it to be a woman. It was Pilar.

'It is she!' she proclaimed on a note of triumph. 'Thank you, my good Vasquez, for all the time you have spent watching here. I knew that, sooner or later, she would come to the prison.'

'Do you mean to tell me,' Marianne said scornfully, 'that this man has been watching the prison for all these weeks purely on the chance of procuring for you this delightful encounter?'

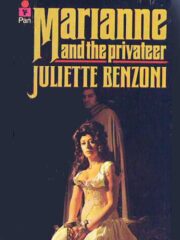

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.