Crawfurd, with a swift movement of his stick, hooked it shut again.

'No,' he said roughly. 'Get out my side. Let me go first.'

'Why? The bollard will help—'

'That bollard,' the old man cut her short grimly, 'is where the mob dismembered the body of the Princesse de Lamballe. You will soil your gloves.'

Marianne turned with a shudder from the worn stone and took the hand which her companion was holding out to assist her from the cab, taking care as she did so not to put too much weight on it. Crawfurd's gout was better than it had been, but he still walked with difficulty.

Seeing them descend from the cab, the guard who had been dozing in the noisome sentry box beside the gate, his gun between his knees, got up and straightened his shako:

'Who goes there?'

'Now then, soldier,' Crawfurd said in a low voice, instantly, much to Marianne's surprise, slipping into a strong Normandy accent. 'No need to shout. Keeper Ducatel is a countryman of mine and we have come, my daughter Madeleine and myself that is, to have a little supper with him.'

A large silver coin gleamed for a moment in the fitful light of the lamp and roused an answering gleam in the eye of the guard, who uttered a shout of laughter and pocketed the coin:

'You should've said so right away, man. He's a right one, old Ducatel, and been here long enough to make a few friends, eh. I'm one on 'em. In you go, then.'

He banged vigorously on the low door which stood at the top of a pair of worn steps and was surmounted by a heavily barred fanlight.

'Hi there! Ducatel! Someone to see you!'

While the driver of the cab was still engaged in turning his horse in the narrow rue du Roi de Sicile, preparatory to waiting for them by St Paul's, the door opened, revealing an individual in a brown woollen cap holding a candle in one hand. This candle he raised until it was practically under the noses of his visitors and then, having apparently recognized who they were by this time, he exclaimed: 'Ha! Cousin Grouville! You're late! We were just going to eat without you. And here's my little Madeleine. Come you in then. You've grown a fine big girl now!'

Endeavouring to sound as provincial as possible, Marianne managed to utter a word of greeting. Ducatel, still continuing his flow of welcoming chat, assured the guard that 'a nice mug of Calvados' should be sent out to him as a reward for his trouble, and then shut the door behind them. Marianne saw that she was in a narrow entrance passage ending in a turnstile. To the right was the guardroom through the half-open door of which four soldiers could be seen smoking and playing cards by the lights of a couple of lamps. Still talking loudly, Ducatel led his guests up to and through the turnstile, then opened a door into another darkened room at the far end of which was a second turnstile. Here, Ducatel paused.

'My lodging looks on to the rue du Roi de Sicile,' he said in a whisper. 'I'll take you there, M'sieur, and we'll make a little bit of noise so that the guards know we're at supper. I'd've had you in by my private door, but it's always best to look open and above board.'

'I can find my way alone, my good Ducatel,' Crawfurd replied in the same tone, nodding approval as he spoke. 'You take the lady to the prisoner you know of.'

Ducatel nodded his understanding and opened the gate:

'This way, then… He's an important prisoner so he's not in the new building. He's been put with the "specials" in the Condé room… very nearly by himself.'

As he spoke, Ducatel unlocked a further door and led Marianne across a courtyard. Crawfurd, meanwhile, turned to the left in the direction of the region known as the Kitchen Court, an appellation more than justified by the powerful smell of greasy soup emanating from it, beyond which lay the keeper's quarters.

As she followed the turnkey, Marianne looked about her with distaste at the buildings surrounding the courtyard and the treeless expanse of cracked paving which was the entrance to the prison itself: high, menacing walls, crumbling and worm-eaten, dotted with barred windows from behind which came an assortment of nightmare groans and shrieks, hideous laughter and the sound of men snoring, and all the other multifarious noises made by the dirty and dangerous portion of humanity penned within by crime and fear. Four floors of rogues, thieves, debtors, convicts escaped and recaptured, murderers, criminals of every kind which the slums of Paris and elsewhere had thrown up into the net of the police. Here was none of the medieval yet not altogether squalid simplicity of Vincennes, for this was not a place for prisoners of state, held for political offences. This was the common gaol, where all the vilest felons were huddled in appallingly overcrowded conditions.

'We had a bit of a job,' Ducatel confided to Marianne, 'to find him a corner that was a bit quiet-like.' He was leading her up a staircase whose wrought-iron handrail betrayed that in the days of the dukes of La Force it had been noble and handsome, though now the treads were cracked and slippery and made the ascent perilous. 'The prison is stuffed as full as it can hold, you know. Never gets much emptier, either. Here we are now…' He indicated an iron-studded door which had come into view in the thickness of the wall. The keeper opened a spy-hole in the door and a little yellowish light filtered out into the passage.

'Someone to see you, M'sieur Beaufort!' he said into the opening before drawing the bolts. Then he added in a lower tone to Marianne: 'It's not my fault, M'dame, but I can't let you have more than an hour or so, I'm afraid. I'll be back to fetch you before they do the rounds.'

'Thank you. You are very kind.'

The door opened almost noiselessly and Marianne slipped through the opening and stood looking a little startled at the sight which met her eyes. On either side of a rickety table, two men were seated, playing cards by the light of a candle. Something which might have been another man was lying curled up in a ball in the corner, on one of the three truckle beds, wrapped in an uneasy slumber. One of the two card players was Jason. The other was an individual about thirty-five years old, tall, dark and active-looking with a good-looking face, regular features, a mocking curve to his lips and bright, inquisitive black eyes. Seeing that a woman had entered the room, the second man rose at once while Jason, too surprised to do more than stare, sat still, the cards still in his hand:

'Marianne! You! But I thought—'

'I thought,' his companion broke in with heavy irony, 'that you, my friend, were a gentleman. Did no one ever teach you to stand up for a lady?'

Jason rose mechanically and as he did so received Marianne full in his arms, laughing and crying at once.

'Oh, my love, my love! I couldn't bear it! I had to come—''

'This is madness! You should be in exile, they may be looking for you…'

But even as he protested, his hands were drawing her face close to his. His blue eyes shone out of a face too deeply weatherbeaten for a few weeks' incarceration to whiten it with a joy which his words tried to deny. His expression, oddly touching in a man of his strength, was like that of a lonely, unhappy child who, expecting nothing, suddenly finds that Father Christmas has come and brought him the most wonderful present. He gazed at Marianne, unable to speak another word, then suddenly crushed her to him and kissed her hungrily, like a starving man. Marianne closed her eyes and abandoned herself to his kiss, feeling as if she could die of happiness. It was nothing to her that the man who held her in his arms was unshaven and filthy dirty, and that the cell smelled anything but sweet. It was obvious that, to her, paradise had nothing more to offer.

From their respective positions by the table and the door, the other prisoner and Ducatel looked on, smiling, and with a degree of awed fascination, at this unexpected love scene. However, when it showed no signs of breaking up, the prisoner gave a shrug and, throwing his cards down on the table, announced: 'Right! I'm not wanted here. Ducatel, will you ask me to supper?'

'With the best will in the world, my lad. You're already expected.'

The effect of this exchange on the two lovers was to bring their embrace to a swift conclusion and they stood looking so shamefaced at the speed with which they had forgotten the existence of everything but themselves that the prisoner burst out laughing:

'It's all right, you needn't look like that, you know! We all know what it is to be in love.'

Marianne gave him a withering glare and turned indignantly to the keeper:

'Is it necessary that Monsieur Beaufort should be forced to endure the company of—'

'Of people like me? Alas, Madame, the prison is overfull and it cannot be helped. But we don't rub along too badly, do we, friend?'

'No,' Jason responded, grinning, in spite of himself, at Marianne's outraged expression, 'it might be a great deal worse! In fact, I'll even introduce you.'

'Spare yourself the trouble,' the other prisoner interrupted him. 'I mean to do that myself. Fair lady, you see before you your genuine gallows bird, not often met with in polite society: François Vidocq of Arras, three times convicted felon and in a fair way to be so again. Deep bow and exits left, as they say in the theatre. Come, Ducatel. I'm hungry.'

'And that?' Marianne said furiously, indicating the black bundle which had continued to jerk and mutter indistinguishably. 'Aren't you taking that with you?'

'Who? The abbé? He'll not trouble you. He's half-cracked and talks nothing but Spanish. Besides, it would be a shame to wake him. He's having such lovely nightmares.'

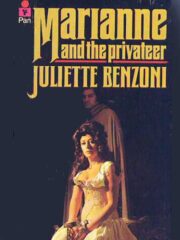

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.