Unable to sleep, she lay turning the problem over and over in her overexcited brain, looking at it from every direction yet without reaching any satisfactory conclusion. The murder seemed to give substance to the theory that Corrado was a monster, yet when she recalled the lithe, powerful figure of the nocturnal horseman the idea became unthinkable. Then was it the face, perhaps, which was repulsive? But a man did not kill his wife on account of a face, however hideous. He might kill in anger – or brutality – or for jealousy. Suppose the child Corrado had borne some striking likeness to another man? But Marianne did not on the whole place much faith in striking resemblances applied to new-born babies. With the exercise of a little imagination, a baby could be made to look like almost anybody. And besides, in that case, why the sequestered existence, why the mask? To preserve for ever from the least breath of scandal the memory of a mother whom the prince had never known and whose memory he could therefore hardly be expected to cherish? No, it was quite impossible…

When it began to get light, at about four o'clock, Marianne, seated in a chair by the open window, had still not closed her eyes, nor had she found any answer to her questions. Her head ached and she was deadly tired. Dragging herself up, she leaned out. All was very quiet. Only the first birds were beginning to sing and tiny forms flitted from branch to branch, without stirring a leaf. The sky was pink and orange with streaks of coral and gold which told that the sun would soon be up. Out in the street, the metal-shod wheels of a cart clanked over the cobblestones and a charcoal-vendor's cry echoed nostalgically. Then, from across the Seine, came the sound of a cannon being fired and at that precise moment up came the sun into a sky filled with belfries chiming the first notes of the Angelus.

This glorious din, which was to last all morning, announced to the good people of Paris that on that day their Emperor was forty-one years old and that today was a holiday and everyone should behave accordingly.

But there was no holiday for Marianne and so as to be sure of hearing nothing of the general celebrations which would gradually take possession of the capital, she carefully closed and shuttered the windows, drew the curtains and, utterly exhausted, flung herself at last fully dressed on her bed and fell instantly asleep.

Marianne's meeting with Arcadius on the evening of the fifteenth of August, while all over Paris people were drinking in the streets and squares and dancing under the street lamps to Napoleon's good health, was almost tragic. His face drawn from the fatigue of several sleepless nights spent haunting every locality where he hoped to find some trace of Lord Cranmere, Jolival reproached Marianne with a good deal of bitterness for what he called her lack of confidence in him:

'Why did you have to come back? What do you hope to do? Bury yourself in this house along with an old fool surrounded by memories of his dead queen and that scheming old woman, still mourning for her murdered lover and her own vanished youth? What are you afraid of? That I won't do all that is humanly possible? Well, don't worry. I am doing it. I'm searching – desperately. I'm searching for news of Mrs Atkins. I spend my nights roaming about Chaillot and the Boulevard du Temple, haunting the Homme Armé and the Epi-Scié. I spend hours in disguise, in the hope of catching a glimpse of one of Fanchon's men, or of Fanchon herself. But I am wasting my time… Do you think I need anything more to worry about – such as knowing that you are here, in hiding, at the mercy of anyone who might denounce you?'

Marianne waited until the storm had blown over. She understood her friend's weariness and discouragement too well to blame him for his outburst, which was prompted purely by his affection for her. To placate him, she was meek, almost humble.

'Please don't be cross with me, Arcadius. I could not stay there, living quietly in the country, while you were working yourself to death here, and while Jason was – was—'

'In prison,' Jolival finished for her tartly. 'A political prisoner. It's not the hulks, you know! And I know he is being treated well.'

'I know. I know all that… or I suppose so, but I was going mad! And when the prince told me he had to come back to Paris, I couldn't stand it. I begged him to take me with him.'

'He should not have done so. But women can always get round him. Well, what are you going to do now? Spend your days listening to Crawfurd extolling the virtues of Marie-Antoinette, telling you in detail all about the Affair of the Necklace or the horrors of the Temple and the Conciergerie? Unless you prefer to hear his wife's life story?'

'I shall certainly listen to anything that she may be able to tell me, because she was born at Lucca and seems to know the history of the Sant'Annas better than anyone; but my real reason for coming back, Arcadius dear, is so that I shall be able to hear any news there is as soon as it is known, and be able to decide what to do… Monsieur de Talleyrand says that things are going very badly and he will tell you—'

'I know. I have just seen him. He told me he was going to seek an audience with the Emperor to try and throw some light on this dreadful business. But I am afraid he won't find it easy to get a hearing. His position is not very encouraging just at present.'

'Why not? He is no longer a minister but he is still Vice-Grand Elector?'

'A grandiose title which is quite meaningless in practical terms. No, what I meant was that Napoleon has heard rumours of his financial troubles and, what is worse, of the reason for them. Our prince was involved to some extent in the Anglo-French negotiations got up by Fouché, Ouvrard, Labouchère and Wellesley. Then there was the failure of Simons Bank – Simons's wife, who used to be a Demoiselle Lange, is an old friend of his – he lost a million and a half there. Above all, there is the four million he was paid by the city of Hamburg to save it from annexation. If Napoleon carries out his intention and annexes it just the same, then Talleyrand will have to pay back the money. At that rate, I don't see him being in high favour at court…'

'Then it's all the more noble of him to try. Besides, if he needs money, I can give it to him.'

'Do you think you have that much? I did not mean to speak of it because I did not want to add to your worries, but this letter came from Lucca five days ago. It came without the quarter's allowance which should normally have been due. You'll forgive me for having read it.'

Foreseeing fresh trouble, Marianne took the letter somewhat reluctantly. She was blaming herself for not having written to the prince herself to tell him of the accident which had resulted in her losing the child. She was afraid of her invisible husband's reaction yet without being very certain what that reaction might be. Something told her now that that was precisely what this letter contained.

In fact, in a brief missive of chilling politeness, Prince Corrado informed Marianne that he had heard of the loss of their mutual hopes, made perfunctory inquiries as to her own health and added that he was in expectation of a visit to Italy on her part in the near future 'so that we may consider the new situation created by this unfortunate occurrence and what steps should be taken…'

'A lawyer's letter!' Marianne exploded, screwing the paper into a ball and hurling it into a corner. 'Consider the situation? Take steps? What does he want to do? Divorce me? I am perfectly willing!'

'Italians do not believe in divorce, Marianne,' Arcadius said sternly, 'and least of all a Sant'Anna! Besides, I should have thought you had had enough of changing husbands every five minutes. Now stop this stupid behaviour!'

'What do you want me to do? Go off there while—No! A hundred times no! Not at any price!'

The explosion of anger which shook her was in reality a cover for her tumultuous thoughts, but for the moment she hated him with all her might, this distant stranger whom she had married in the belief that, in spite of all, she would still keep complete freedom of action, yet who now dared, even from a distance, to dictate to her as lord and master and make her feel the curb. Go back to Lucca! To that house full of hidden dangers where a madman worshipped a statue and offered up human sacrifices to it, where another rode out only at night, wearing a mask? Not now, at all events. If she were to do what she had to do here, Marianne had to be free – free! On the other hand, this act of cutting off her supplies was ominous and more than a little awkward. This was not the moment for anything like that, either, when she might need to bribe people, buy men and weapons… an army, even, to snatch Jason from the unjust condemnation ahead of him. Moreover this letter, the first she had received from Prince Sant'Anna, represented another source of danger. What if it had been opened, by any chance, by the Emperor's Cabinet Noir? A knowledge of its contents might easily give him the idea of removing Marianne definitively from the Beaufort affair by sending her back to her own distant estates. What could she do about it… Then something else about the letter struck her as alarming. What were these 'steps' the prince considered taking? Did he think he could compel her to return to Napoleon so that, at all costs, he might have the child he wanted? Logically, that was the only solution, since the prince could not divorce her. If he had any idea of attending to the matter himself, he would surely have done so long ago? Then what? Why this letter, this thinly disguised command to return to Lucca? What for?

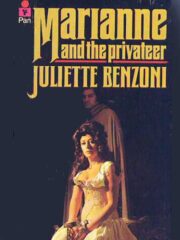

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.