But Marianne was conscious only of the last words. 'Return to Paris? You are returning?'

'I must. I have to be there for the Emperor's birthday on the fifteenth of August. This year, to add to the magnificence of the occasion, His Majesty has decided to hold the unveiling of the bronze column he has set up in the Place Vendôme in honour of the Grand Army, made from the metal of twelve hundred and fifty cannon captured at Austerlitz. I am not at all sure it is such a brilliant idea. It can scarcely be very agreeable to the new Empress, seeing that a good half of the cannon in question belonged to Austria. But the Emperor is so delighted with the figure of himself as a Roman emperor which is to surmount the column that I suppose he wants all Europe to have an opportunity of admiring it.'

But Marianne's thoughts were very far from the column in the Place Vendôme, so far indeed as to make her forget even her manners and break in on the prince unceremoniously:

'If you are going back to Paris, take me with you!'

Take you, eh? What for?'

By way of a reply, Marianne held out Jolival's letter. Talleyrand read it carefully and slowly. By the time he reached the end there was a deep furrow between his brows, but he returned the letter without comment.

'I must go back,' Marianne said again after a moment, in a choking voice. 'I cannot stay here, safe in the sunshine, while Jason is in this dreadful danger. I – I think I should go mad. Let me come with you.'

'You know that you are forbidden to go – or I to take you. Don't you think you will only make matters worse for Beaufort if the Emperor hears that you have disobeyed him?'

'He will not hear. I shall leave my baggage and my servants here with orders to admit no one to my room and to say that I am ill in bed and will see no one at all. It will cause no surprise. I did very much the same before you arrived. The people here probably think I am mad anyway. With Gracchus and Agathe here, I know that no one will enter my room and find out the deception. Meanwhile, I will go back to Paris disguised as – let me see – yes, disguised as a boy. I shall be one of your secretaries.'

'Where will you go to in Paris?' the prince objected, looking not at all relieved. 'Your house is being watched, you know that. If the police were to see you going in you would be arrested on the spot.'

'I thought…' Marianne began, sounding suddenly rather shy.

'That I would take you in? Yes, well, I thought of it myself for a moment, but it would not do. You are known to everyone in the rue de Varennes and I do not think everyone is to be trusted. There is a likelihood that you would be betrayed and that would not help matters, either for you or for myself. I am not, you will recall, on the best of terms with His Majesty… even if he has asked me to go and unveil his column!'

'Then it can't be helped. I will go somewhere else – to a hotel perhaps.'

'Where your disguise would be seen through in a moment. No, you are being altogether foolish, my child. But I believe I have a better idea. Go and make what arrangements you need. We are leaving Bourbon this evening. I will see that you have some man's clothes and you can pass as a young secretary of mine until we reach Paris. Once there, I will take you to – but you will see. No need to speak of that now. You are set on this piece of folly?'

'I am,' Marianne said firmly, flushed with joy at a degree of assistance she had scarcely dared to hope for. 'I feel that if I am near him, I shall find some way to help him.'

'He is a lucky man,' the prince said with a faint, rather wistful smile, 'to have such a love. Ah, well, I seem to be fated to refuse you nothing, Marianne! And perhaps, after all, it may be best to be within reach. An opportunity may occur, and if it should, you will be there to take advantage of it. For the present, let us go in. Good heavens, child! What are you doing?' The last words were accompanied by a vain attempt to draw back his hand which Marianne had carried gratefully to her lips. 'Haven't I chosen you for my daughter, after all? I am merely trying to prove myself a tolerable father, that is all. Though I can't help wondering what your own father would say to all this!'

Arm in arm, the lame prince and the young girl made their way slowly back to the village, leaving the lake to the company of the ducks.

Eleven o'clock was striking from the Quinquengrogne Tower when Talleyrand's coachman set his team bowling along the road to Paris. As the coach began to move, Marianne looked up to the window of her room and saw, behind the closed shutters, the glimmer of the lamplight showing through, just as it had done every night since her arrival. No one would ever think that it shone on an empty bed, in an empty room. Gracchus and Agathe had received strict orders, although Gracchus, especially, had proved hard to convince. He had been deeply shocked to think that his beloved mistress could consider setting out on such a perilous adventure without his stalwart support. Marianne had been obliged to promise that she would send for him as soon as possible, and certainly at the first hint of danger.

The darkened countryside sped past the windows of the coach and very soon the motion lulled her and she slept, with her head on Talleyrand's shoulder, and dreamed that she was going to fling wide the gates of Jason's prison all by herself with her bare hands.

Part II

THE PRISONER

CHAPTER SEVEN

The Queen's Lover

The house, when Marianne entered it with Talleyrand, was dark and silent. An expressionless servant in staid, brown livery bearing a branch of candles preceded them up a broad, black marble staircase adorned with a handsome, gilded rail of wrought iron to the first-floor landing off which, in addition to a number of darkened salons, there opened a room like a large bookroom but so filled with furniture, pictures, books and works of art of all kinds that, if he had not come to meet them, Marianne and her companion might have had some difficulty in distinguishing the bald head and heavy, stooping figure of the Englishman, or rather Scotsman, Crawfurd.

'When I lived in this house,' the prince had observed with a rather forced lightness of tone, 'this was my library. Crawfurd has made it a shrine of a somewhat different order…'

By the dim light of a few, scattered candles, Marianne saw to her astonishment that all the pictures and other objects, or nearly all, were of the same person. In bronze, in marble and on canvas, everywhere the proud, lovely face of Queen Marie-Antoinette stared down at the newcomers. Even the furnishings had come from the Petit Trianon and nearly everything in the crowded room, fans, snuff-boxes, handkerchiefs, books, bore either the queen's arms or her monogram. On the walls, which were hung with grey silk, were many gilt frames in which the occasional note in her own handwriting alternated with portraits and miniatures.

While Talleyrand shook hands with Crawfurd in the American fashion, Quintin Crawfurd himself was watching with a melancholy smile the obvious astonishment with which Marianne's eyes took in the room. At last he said, in the gruff voice which still retained some traces of a highland accent: 'From the first day on which it was my privilege to be presented to her, I vowed to devote my life to the service of the martyred queen. I did all that I could to snatch her from the hands of her enemies and restore her to happiness. Now I honour her memory.'

Then, as Marianne was silent, awed by the strange passion which throbbed in the old man's voice, he went on: 'Your own parents died for her, and furthermore your mother was an Englishwoman. My house shall shelter you against all your foes, and any that may try to tear you from it, or to harm you in any way, shall not live to boast of it.'

He gestured towards a pair of massive pistols which lay on a table and, on a chair near by, an ancient, heavy claymore whose glittering steel blade spoke of the assiduous care which kept it ready for instant use. Yet in spite of the somewhat theatrical drama of his welcome, Marianne could not help finding Crawfurd rather impressive, and he was undeniably sincere in what he said: he was a man who would kill rather than betray his guest. Somehow, startled as she was, she managed to utter some polite words of thanks, but he cut her short at once:

'Not at all. The blood of your family and the prince's friendship make you doubly welcome here. Come, my wife is waiting to meet you.'

If the truth were known, Marianne's feelings when, as they drew near to Paris, Talleyrand had told her that he planned to ask for the Crawfurds' hospitality on her behalf, had been less than enthusiastic. Her recollection of the odd couple she had glimpsed only once, in the Prince of Benevento's box at the theatre, was strange and rather disturbing. The woman, in particular, had both intrigued and frightened her a little. She knew that before her marriages, first, morganatically, to the Duke of Würtemberg, then to the Englishman Sullivan, and then to Crawfurd, she had passed the early years of her life with the Sant'Annas and must therefore be familiar with them. But more than this, she had been conscious of Eleonora Crawfurd's dark gaze resting on her for a long time across the width of the house that night. There was admiration in the look, certainly, and a good deal of curiosity, but there was also something else, a kind of detached irony which did not suggest very friendly feelings. On the strength of this look, she had felt a peculiar reluctance when Talleyrand's coach had turned into the rue d'Anjou-St-Honoré on that evening of the fourteenth of August and drawn up at the door of what had formerly been the Hôtel de Créqui. It was a pretty, eighteenth-century house which, two years earlier, had been the home of Talleyrand himself, while the wealthy Crawfurd had lived, since 1806, in the Hôtel Matignon. The exchange had been made partly as a matter of private convenience, for Matignon was far too big for Crawfurd's household, and partly in obedience to the Emperor's desire to see his Minister for Foreign Affairs installed in a suitably grand establishment, to which, be it said, the minister in question had been by no means averse.

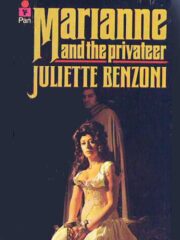

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.