'Well?' Savary asked.

'I shall obey,' she said reluctantly.

'Good. You will be gone in – shall we say, two days?'

What good would it do to plead when the master commanded? It might be that the Emperor meant his heavy hand to fall lightly and protectively, but for all that, Marianne felt its grip grinding her bones and crushing the fibres of her being quite as painfully as any medieval instrument of torture. No longer able to endure the minister's solemn face and crocodile sympathy, she gave him a slight bow and left the room, leaving it to the gloomy butler, Jeremy, to escort him to his carriage. She wanted, above all, to be alone to think things out.

Savary was right. It would do no good to rebel openly. Better to seem to bow, even though no force on earth should make her give up the fight!

Two days later Marianne left Paris, accompanied by Agathe and Gracchus, bound for Bourbon-l'Archambault. It had been her first intention to join Arcadius de Jolival at Aix-la-Chapelle, but that great Rhineland spa was very much in fashion that summer and Marianne felt little inclination for society after all that she had been through, and would go through, until Jason Beaufort was proved innocent and finally exonerated. Moreover, Talleyrand, who had arrived at her house on the heels of Savary, had advised her strongly against the historic capital of Charlemagne:

'There is certainly plenty of company to be met with there, but it is company of a very doubtful kind. Every exile and troublemaker is flocking there to the king of Holland now that the Emperor has to some extent set him aside by annexing his kingdom. Louis Bonaparte is the most lachrymose creature of my acquaintance and now he is behaving precisely as if he had been driven from his ancestral acres by some remorseless tyrant. Then there is our Lady Mother, also, with her endless prayers and still more endless economies. To be sure, my dear friend Casimir de Montrond has obtained permission to visit the place but, deeply devoted to him as I am, I cannot but feel he has a talent for courting disaster and God knows you have had enough of those… No, you had better come with me.'

For eight years past, it had been the Prince of Benevento's habit to depart each summer with unfailing regularity to drink the waters at Bourbon. His bad leg and his rheumatic pains were, if not greatly eased thereby, at least made no worse and no human strength, no cataclysm in Europe could have prevailed to stop him taking his cure when July came round. He had enumerated the charms of the quiet, pretty little town to his young friend in glowing terms, adding the further persuasions that it was not nearly so far from Paris, that seventy leagues was far more easily covered than a hundred and fifty, that it would be far better to write to Jolival to join her in Bourbon, that it was far easier to sink into a kind of obscurity, and the consequent freedom of action which resulted from it, in a small town than in a city full of people to whom one was known and, finally, that those in disgrace had a duty to stick together:

'You can make up my table at whist and I shall read to you the works of Madame du Deffand. We will reshape Europe between us and talk scandal about all those who talk scandal about us. That ought to keep us busy, eh?'

Marianne had agreed. While Agathe packed her clothes and Gracchus spring-cleaned the big travelling coach, she had sat down to write to her friend Jolival a long letter recounting all that had occurred. She finished by asking him to come back as soon as he was able, with or without Adelaide, and come to her at Bourbon. It made no difference to tell herself that there was certainly nothing the literary Vicomte could do to assist Jason, she was still convinced that, if only he were there, everything would at once seem better. She was perfectly well aware that if he had been there Cranmere's trap would not have worked nearly so well because, being less trusting and a good deal less emotional than Marianne, he would undoubtedly have smelled a rat and acted accordingly.

But the harm had been done and now they could only do everything possible to repair it and to bring the real murderers of Nicolas Mallerousse to justice. In any enterprise of that kind, Arcadius was a priceless ally because he knew far better than Marianne herself those sinister inhabitants of the Parisian underworld among whom the Englishman had found his confederates.

The letter had been entrusted to Fortunée Hamelin, who was even then on the point of setting out hot foot for Aix-la-Chapelle, for she, like her friend Talleyrand, had heard that the irresistible Count Casimir was to take the waters there and no power on earth could have kept her from the man who, with Fournier-Sarlovèze, shared her amorous and highly inflammable heart. The fact that Fournier was at that moment in prison in no way deterred her.

Well, at least he can't run off with anyone else while I'm away,' she had remarked, with her usual airy cynicism, regardless of the fact that she herself was preparing to fly to the arms of the handsome general's rival.

So Fortunée had gone the day before, promising to give the letter to Jolival before she so much as set eyes on Montrond, and reassured on that point, Marianne had set out sedately for the Allier, where she was to meet Talleyrand. It had been his intention, before going to Bourbon, to spend a few days on his estates at Valençay, partly to pay his respects to his permanent though unwilling guests, the Spanish princes, and partly to talk business with his agent, the Prince of Benevento's financial affairs having suffered a grievous blow through the failure of Simons Bank in Brussels.

Marianne left Paris on the fourteenth of July 1810, not without a good deal of regret. Quite apart from the thought that she was leaving Jason in the hands of the police, she found herself hating to leave her own dear house. In spite of Savary's reassuring words, she wondered how long it would be before she saw it again, for she knew in her heart that sooner or later she would disobey the Emperor and that if Jason were brought to trial, if all her own and Jolival's efforts proved vain, then no power on earth could keep her from him at that moment. Sooner or later, she would incur the wrath of Napoleon… and God alone could say how far that wrath might go. The Emperor was perfectly capable of ordering the Princess Sant'Anna bade to Tuscany and forbidding her to leave it. He might force her to remain shut up in the villa, so beautiful and yet so terrifying, from which she had fled once before after a night of nightmare horror.

The mere thought of it made Marianne's skin prickle with fear. Ever since losing her child, she had been unable to think without apprehension of the moment when the prince in the white mask should learn that the longed-for heir would not be forthcoming, indeed, would never be. She had put off from day to day the moment of writing the fatal letter, so great was her dread of what might be his reaction. Something told her that if the Emperor, in his anger, were to have her returned to the palace of Sant'Anna she would never be able to escape from it again. The memory of Matteo Damiani had not yet faded from her mind.

She had often wondered what had happened to him. Donna Lavinia had told her as she was leaving, that Prince Corrado had confined him in the cellars, that no doubt some form of punishment would follow. But how could he punish a man who all his life had served him, and served his family devotedly… and one moreover who certainly knew his secret! With death? Marianne could not believe that Matteo Damiani had been killed, for he himself had killed no one.

The horses trotted on towards Fontainebleau and the sun splashed gaily through the moving curtain of leaves, but Marianne paid no attention to the road slipping by outside the windows of her coach. Her mind remained curiously divorced from the present and divided in the strangest way, part of it dwelling on Germany and her friend Jolival, of whom she had such high hopes, and part, the greater and more vulnerable part, roving about the ancient prison of La Force which she knew so well.

There had been a day when Adelaide, in a mood of nostalgia, had taken her to the old quarter of the Marais to show her her old home, a beautiful building made of pink brick and white stone dating from the time of Louis XIII, a neighbour of the Hôtel de Sévigné, but horribly scarred and disfigured by the warehouses and rope-walks which had taken it over during the Revolution. La Force was not far away and Marianne had glanced with revulsion at the squat, blank shape, under the low mansard roof, the stout though leprous walls and the low, heavily barred gate with its two rusty lanterns. It was a sinister gate, indeed, a dirty rusty-red in colour as if it were still soaking up the blood which had washed about it during the massacres of September 1792.

Marianne's elderly cousin had told her about those massacres. She had seen them from her hiding place in a garret of her own house. She had told of the ghastly death of the gentle Princesse de Lamballe. The story returned to Marianne's mind now in all its hideous detail and she could not repress a shudder of superstitious horror at the fate which seemed to be drawing Jason Beaufort inexorably along the same path as that taken by the martyred princess. He had gone so quickly from her house to what had been her prison. And had not Marianne herself heard her ghost weeping in the house where Madame de Lamballe had sought oblivion from a king's ingratitude? To Marianne's impressionable and highly sensitive mind it seemed a warning of disaster. What if Jason, too, were to leave La Force only to go to his death?

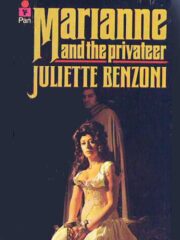

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.