'Go in and see.'

Jason entered first and after a quick start moved instinctively to block his companion's view, and at the same time to keep her from stepping in the blood which covered the room. But it was already too late. She had seen what lay within.

She gave a single horrified shriek, then turned, her knees giving way beneath her, to escape the nightmare vision, only to come full against the inspector's large chest, blocking the doorway.

In the middle of the room, the legs half-hidden under the billiard-table with its torn cloth, lay a gigantic corpse, with gaping throat and eyes wide open on eternity. Yet for all the bloodless pallor of the face, for all the terrifying fixity of the expression, rigid in a look of horrible surprise, there was no mistaking the identity of the man who lay there, in that place which had once been built for amusement and was now so dreadfully transformed into a scene of carnage. It was Nicholas Mallerousse, Marianne's adoptive uncle, alias the seaman Black Fish, the friend of prisoners escaping from the English hulks and the man who had sworn to destroy Francis Cranmere or die in the attempt.

'Who is this man?' Jason asked tonelessly. 'I have never seen him before.'

'Ah! Is that so, indeed?' the inspector said, making vain attempts to disengage himself from Marianne who was clinging to him, sobbing convulsively, in the first stages of hysteria. 'And yet your initials were found on the razor which killed Nicolas Mallerousse.

'Now then, lady, now then, if you please! I've better things to do than stand here supporting you.'

'Leave her alone!' Jason cried fiercely, snatching Marianne away from the inspector who had started to shake her in his efforts to get free. 'No one looks to a policeman for compassion! If this poor fellow is indeed Nicolas Mallerousse, as you claim, then this young woman has just received a terrible shock. Get her out of this slaughterhouse, I implore you, or the Emperor shall hear of it, I swear to you! Come, Marianne, come with me…'

Still talking, he lifted her shuddering form and carried her outside. Piques let them go and merely indicated a stone bench which stood beside the path, backed by a bed of tall white lilies whose heady scent filled all that part of the garden. Jason laid down his burden and asked for someone to be sent to find Gracchus-Hannibal Pioche and tell him to bring the carriage for his mistress. Inspector Pâques, however, had his own views:

'Not so fast. I haven't finished with this lady yet. You told me it came as a shock to her that the body was that of Nicolas Mallerousse? Why should that be, now?'

'Because he was a good friend to her. She was very fond of him.'

'Do you expect me to believe that? The shock was caused by the sight of the blood and maybe because she had not thought to be confronted with your handiwork.'

'My handiwork! Are you accusing me of this disgusting piece of butchery? Simply because you found a razor with my initials on it? Razors can be stolen—'

'But motives can't. And you had two, two very good ones.'

'Two motives? How should I have two motives for murdering a man I'd never even met?'

'At least two,' Pâques amended, 'each better than the last. Mallerousse had been on your tail ever since you came to France, trying to get proof of important smuggling ventures you were involved in. You killed him because he was about to arrest you just as you were leaving France with your holds full of—'

'Champagne and burgundy!' Jason cried exasperatedly. 'You don't kill a man for the sake of a few bottles of wine!'

'If what that letter has to say is true we shall find something else besides that will give us all the proof we need. As for the second motive. The lady herself supplies that. You killed him to save her!'

'To save her? Save her from what? I tell you she—'

'From this! We found it on the body. I don't doubt she knew Mallerousse well enough, or that he, poor devil, knew a good deal more about her than she liked. But I can't imagine her being so very fond of the man who was carrying this paper. Here, Germain, fetch a lantern over here!'

One of the policemen came over to them. The light from his lantern fell on a scrap of yellow paper, the sight of which was enough to rouse Marianne from the depths of horror and grief that had overwhelmed her. Still shaken by sobs, she had heard what was said without being able to gain sufficient control of herself to respond to the inspector's accusations and Jason's angry replies. But this piece of paper, the yellow paper she had seen once before on that day in the Place de la Concorde, in the hands of her worst enemy, acted on her as a counter-irritant because it gave her clear proof; it was the signature added to the nightmare in which she and Jason were caught.

She held out her hand and, taking the paper from the inspector, unfolded it and read it quickly. Yes, it was the same as the one she had already seen, except that it had been brought up to date and the name 'Princess Marianne Sant'Anna' substituted for that of 'Maria-Stella'. But the contents, the accusation that the Emperor's mistress was a spy and a murderess still being sought by the law in England, were the same as ever, still characteristically vile.

Holding it distastefully between finger and thumb, Marianne returned the yellow broadsheet to the inspector:

'You were quite right to keep me here, Monsieur. No one is better able to give you the full story of that abominable piece of libel. I have seen it before. I will tell you, too, how it was I came to know Nicolas Mallerousse, of the kindness I received from him and why I had good cause to love him, whatever ideas you may have formed on the strength of one anonymous letter and another, equally anonymous pamphlet.'

'Madame—' the police officer began impatiently.

Marianne held up her hand. She looked proudly at the inspector with an expression at once so haughty and so candid that his eyes fell before hers:

'Allow me, Monsieur! When I have done, you will see the impossibility of further accusations against Monsieur Beaufort because what I have to tell you will reveal the names of the real perpetrators of this – this hideous crime.'

Her voice failed her as once again her memory set before her every detail of the scene she had just beheld. Her friend Nicolas, so kind and brave, basely slaughtered by the very ones he should have brought to justice. How it came to pass that this should have happened in this house, the house in which Jason was living, a house which belonged to a man of the utmost respectability, Marianne did not know, but she knew with all the infallible insight of her grief and anger, and her hatred also, who had done this. If she had to cry it aloud to the whole of Paris, if it cost her the last shred of her reputation, she would bring the real culprits to justice!

Inspector Pâques, meanwhile, began to lose some of his assurance in the face of a woman who spoke with such firmness and certainty:

'All this is all very well, Princess, but the fact remains that someone committed the crime and the body has been found here…'

'Someone committed the crime but it was not Monsieur Beaufort! The real murderer is the author of that pamphlet,' Marianne cried, pointing to the yellow paper which Pâques still held in his hand. 'He is the man who has hounded me ever since the evil day I married him. He is my first husband, Lord Francis Cranmere, an Englishman—and a spy.'

Marianne could feel, suddenly, that Pâques did not believe. He was looking alternately at the yellow paper and at Marianne with an odd expression on his face. At last he shook the paper softly under her nose:

'In other words, the man you killed? Do you take me for an imbecile, Madame?'

'But he is not dead! He is in France, he goes by the name of the Vicomte—'

'Think of another story, Madame,' the inspector interrupted her roughly, 'and do not try to divert me with these taradiddles! It is easy enough to accuse a ghost. This house is supposed to be haunted, let me remind you. Perhaps that may provide you with a further exercise for your imagination. For myself, I believe in facts.'

In her indignation, Marianne might have continued to plead, reminding this suspicious policeman of her position in society, her influence with the Emperor, her connections, even, despite the shame evoked by the recollection of those dark hours in her life, of her past record as one of Fouché's most trusted agents. But four more policemen came down the path at that moment. Two carried lanterns while the other two were maintaining a firm grip on a burly individual dressed in a seaman's rough woollen jersey which had seen better days.

'Here, Chief!' one of the men said. 'We found this fellow skulking in the bushes, down by the wall on the Versailles road. He was trying to climb over and make off.'

'Who is he?' growled Pâques.

The answer to his question came from an unexpected quarter. It was Jason who spoke. He had taken the lantern from the hands of one of the policemen and held it up so that the light fell on the prisoner. The face emerging from the shadows and from the filthy collar of the seaman's jersey was bony and unprepossessing, with a broken nose and eyes like black coals.

'Perez! What are you doing here?'

The man appeared to be labouring under all the effects of considerable terror. Strong as he looked, he was shaking so that only the grip of the two policemen kept him on his feet.

'You know this man?' Pâques asked, frowning.

'He is one of my men. Or rather, he was, for I discharged him from my ship when we docked at Morlaix. He is an unmitigated rogue,' Jason said sternly. 'I have no idea what can have brought him here.'

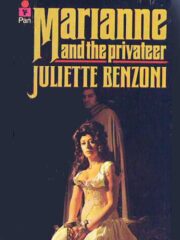

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.