'A conspirator! I? Jason flung at her. 'And you believed it? Surely you knew me well enough?'

'No,' Marianne said seriously, 'no – I don't really know you at all. Remember I saw you first as an enemy, and then as a friend and a saviour, and then at last as someone – someone indifferent.' The word was not easy to say, but Marianne did say it firmly. Then she went on, very gently: 'Which of these men is the real one, Jason? For from indifference you seem to have come to dislike, even to hate me?'

'Don't talk such rubbish,' Jason retorted sharply. 'What man could be indifferent to a woman like you? There is something about you which drives a man to commit the wildest follies. One must either love you to distraction – or want to wring your neck! There can be no half-measures.'

'You – you seem to have chosen the second alternative. I can't blame you. But before I go, there is one thing I should like to know—'

He was standing with his back to her, staring out, unseeingly, at the rain streaming down the windows and at the blackness of the garden beyond.

'What?'

'This visitor – who was so important as to bring you back from the Queen of Spain. I should like to know – forgive me – I should like to know if it was a woman?'

He turned and looked at her again, but this time there was in his eyes something like an involuntary tenderness:

'Does it matter so much?'

'More than you could ever believe. I – I will never ask you anything else. You will never hear of me again…'

It was said in a tone of such doleful resignation, and with such humility, that it found the chink in his armour. A force which he could not control brought the privateer to his knees beside her, imprisoning both her hands in his:

'Little fool! That visit was important only from a business point of view. And the visitor was a man, another American, a boyhood friend of mine, Thomas Sumter, who has just gone off to supervise the loading of my ship. You probably don't know, but on account of the blockade a number of major French exporters are using American vessels to transport their goods. One of these is a delightful lady at Rheims, Madame Veuve Nicole Cliquot-Ponsardin, the head of great champagne caves, who has done me the honour to entrust her wares to me. Thomas has just been settling our latest agreement and has driven off to Morlaix tonight to arrange for the cargo's conveyance to – well, to somewhere outside the Empire. That is all my conspiracy. Are you satisfied?'

'Champagne!' Marianne cried, laughing and crying at once. 'It was all about champagne! And I thought—Oh dear, it's too much, it's really too wonderful… too funny! I was right when I said I did not know you at all!'

But Jason had only smiled perfunctorily at her relief, and there was no laughter in his eyes as he searched her radiant face with painful eagerness:

'Marianne, Marianne! Who are you yourself with your childlike innocence and the artfulness of a woman of the world? Sometimes you are as clear as day, and at others full of strange shadows, and it may be I shall never know the truth about you.'

'I love you – that is all the truth.'

'You have the power to make my life a hell, and to turn me into a devil. Are you a woman or a witch?'

'I love you – I am only a woman who loves you.'

'And I almost killed you. I wanted to kill you…'

'I love you. I have forgotten it already.'

The strong, brown hands had moved steadily up Marianne's arms and folded round her, drawing her close to a hard, warm chest, and Jason's lips were on her eyes, her cheeks, were seeking her mouth. Trembling with a joy so great that for an instant it seemed that she would die, Marianne abandoned herself to the arms that now held her fast, pressing herself close to Jason and closing her eyes which were so full of tears that they overflowed and her cheeks were wet with them. Their kiss tasted of salt and fire, bitter-sweet, with all the passion and tenderness of a thing long awaited, long desired, long prayed for without real hope of that prayer being answered. It was eternity in a few seconds, broken off only to begin again, more passionately still. It was as if neither Jason nor Marianne could ever quench their grievous, burning thirst for each other, as if both were trying to cram into this fleeting moment of happiness all their share of paradise on earth.

When at last they drew apart a little, Jason took Marianne's chin between his fingers and pushed her head up a little until the candlelight shone in the marine deeps of her eyes.

'What a fool I've been,' he murmured. 'How could I ever have imagined for a moment that I could live the rest of my life away from you? You are a part of myself, my flesh and blood!… Now what are we going to do? I cannot keep you with me, and you have no right to stay. There is—'

'I know,' Marianne said quickly, laying her hand on his lips to keep him from uttering the names that would have broken the spell. 'But these few hours belong to us. Surely we can forget the real world for a few moments more?'

'Like you, I wish we could – oh, how I wish we could!' he said desperately. 'But Marianne, there is this peculiar behaviour of Cranmere's, this false information – and all that it cost you—'

'The money is nothing. I have more than I know what to do with.'

'Nevertheless, I will repay you. But it was not the money I was thinking of. Why did he spin you this yarn?'

Marianne laughed. 'Just for the sake of the money, of course. You said so yourself, he was undoubtedly in need of it and he found a perfect means. The only thing to do now is to forget it.'

She slid her arms tenderly round his neck and tried to draw him to her once again but Jason unfastened her encircling arms very gently and got to his feet:

'Can you hear? There is a window banging in the next room.'

'Call one of the servants.'

'I sent them all to bed before Thomas came. My business affairs are my own concern.'

He moved towards the door which led to the adjoining room and Marianne followed him automatically. Now that the rain had stopped and everywhere was quiet, she sensed a strangeness in the atmosphere of the house, as if it were full of the rustle of skirts, faint whisperings which were probably nothing more than lingering drops of water dripping from the trees on to the gravel paths outside. The room where the window was banging, a large, almost empty salon, was dark but, glancing out of the windows, Marianne thought she saw lights flitting among the shadows in the grounds that ran down to the Versailles road. There was something ominous about them in the thick dark out there, and she hurried after Jason, who was making the window fast.

'I thought I saw lights in the garden. You saw nothing?'

'Nothing at all. Your eyes have been playing tricks on you.'

'And the noises?… Did you hear nothing? As it were a rustle of silk, a sighing?'

It might have been the effects of darkness, for it was almost completely dark, the lights in the next room casting only a feeble shaft through the half-open door, but Marianne found that her hearing and her mind seemed attuned to a host of faint, disquieting sounds. It was as if every board, every panel, every piece of furniture in the house had taken on a life of its own – a frightening feeling.

Startled by the odd note in her voice, Jason folded her once more in his arms, clasping her to him gently, like some fragile, precious object, then, as he realized that she was burning hot, he began to worry:

'You're feverish! It is that which makes you see and hear things. Come, I can feel you shivering… You need care. Oh, my God, and to think I…' He tried to urge her forward but she hung back, staring wide-eyed into the darkness, which now began to seem less black.

'No. Listen! It is like someone crying. A woman… she is crying to warn us…'

'Any moment you will tell me you are another who has seen the poor princess's ghost! Enough of this, Marianne. You are doing yourself no good and I am afraid that I have made matters worse. We must not stay here.'

Without further argument, he picked her up in his arms and carried her through into the other room and shut the door carefully behind them before depositing his burden on a small sofa. Having first wrapped Marianne in her silken cloak and placed a cushion underneath her head, he announced his intention of rousing the cook to bring her some hot milk. Walking over to the corner by the bookcase, he pulled the bell rope which had been concealed there. Muffled to her chin in the green silk, Marianne followed him with her eyes.

'It's no good,' she said unhappily. 'The best thing is for me to go home. But – I didn't see the ghost, you know. I heard it. I know I did.'

'Don't be so silly. There is no ghost outside your own imagination.'

'There is… it was trying to warn us—'

Quite suddenly, the house seemed to be wide awake. Doors opened and shut noisily and there was a sound of hurried footsteps. Even before Jason could reach the door to inquire what was afoot, it was flung open to admit a bewildered-looking footman bearing all the signs of one who had dressed in great haste:

'The police! It is the police, Monsieur!'

'Here? At this hour? What do they want?'

'I – I do not know. They made the lodge keeper open the gate and they are already in the grounds.'

Seized with a horrible foreboding, Marianne sat up and began feverishly putting on her cloak, tying the silken strings with trembling hands. She stared up at Jason with frightened eyes. The thought in her mind was that Francis might have cheated her and, without the least shadow of proof, have informed on Jason as a conspirator.

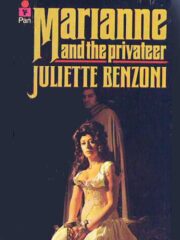

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.