'Not quite as clear as you think perhaps. Do, please, be good enough to wait for me. It will in any case be necessary for me to have the gates opened – unless of course you wish to take these gentlemen out over the wall?'

Hurrying down the great marble staircase as fast as her injured hip allowed, Marianne forced herself to think. The officer had quite obviously not believed in Fournier's rather unlikely explanation. They must think of something else, but unfortunately Marianne's mind, still wholly taken up with Jason and the danger threatening him, was not finding it easy to adjust to this new demand. She was burning to run to Passy and warn Jason and now this stupid duel had come to prevent her and to hold her up for goodness knew how long.

When she emerged into the garden the darkness was already growing perceptibly less thick. A pale band of light showed in the east, revealing a scene of total confusion among the law officers and their prisoners. Fournier was defending himself vigorously against the efforts of two men to apprehend him, while the officer in charge was engaged in gallant but futile attempts to scale the wall from inside which, in the absence of the horse which had assisted him in his entry, was proving an altogether impossible task for a man of unathletic build and hampered, moreover, by a pair of outsize boots. Of Chernychev there was no sign, but from the other side of the wall came the sound of receding hoofbeats.

Realizing the futility of his endeavours, the officer abandoned his assault on the wall and returned to where Fournier was still putting up a spirited defence. He was by this time thoroughly out of temper:

'You are wasting your efforts. Your accomplice has got away, but we shall catch him and meanwhile you shall pay for both, my lad.'

'I am not your lad!' Fournier exploded furiously. 'I am General Fournier-Sarlovèze and I will thank you, officer, not to forget it!'

At this, the other drew himself up and gave a military salute:

'Pardon me, General. I had no means of knowing! Nevertheless, you are my prisoner – I am sorry to say. Not but what I'd rather have kept a hold of the other fellow. It passes me why you should have helped him as you did by hurling yourself on my men like that.'

Fournier gave a shrug, and favoured the officer with a mocking smile:

'I told you. He's a friend of mine. Don't you believe me?'

'How can I, General, when you would not give me your word that you were not engaged in fighting a duel?'

Fournier was silent. Deciding that it was time for her to intervene, Marianne laid her hand, at once soothing and cajoling, on the officer's arm.

'And if I were to ask you to close your eyes for once, Officer? I am Princess Sant'Anna – a close friend of the Emperor.' A timely recollection of the invitations she had received from Savary prompted her to add: 'The Duke of Rovigo is well disposed towards me, I believe, and no one, after all, has been killed or injured. We might—'

'A thousand regrets, Princess, but I must do my duty. Setting aside any questions my men might ask and the awkwardness of explaining matters to them, I should not care to put myself in the position of a colleague in a similar situation. He was lenient, the matter was found out and it broke him. His Grace of Rovigo is very strict in matters of discipline. But then, you know him, Highness, and must surely know this? Now, General, if you please…'

Unwilling to admit defeat, Marianne would have gone on pleading and in her distress at the thought that Fournier would be imprisoned again because he had defended her she might well have committed the folly of offering the man money, had not Fournier himself intervened: 'I am coming,' he said; then, turning to Marianne, went on more quietly: 'Do not worry about me, Princess. This is not the first duel I have fought and the Emperor knows me well enough. It seemed better to let the Cossack escape. The thing might have proved more serious for him. The worst I can expect is a few days in prison and a little holiday at home at Sarlat.'

Marianne's sensitive ear did not miss the little note of regret in the hussar's voice. Sarlat might hold for him all the sweetness of home but it also meant inaction, idling away his time away from the battlefields which were his life and, but for this stupid affair, he would soon have been on his way back to in Spain. To be sure, she also remembered what Jean Ledru had told her of the horrors of war in that God-forsaken country but she knew that no such considerations weighed with the finest swordsman in the Empire and, indeed, would probably only whet his appetite for the fray.

She held out both hands impulsively. 'I will go to the Emperor,' she promised. 'I will tell him all that has passed and what I owe to you. He will understand. I will tell Fortunée, too. Though I doubt if she will be as ready to understand.'

'Not if it were anyone but you!' Fournier said, laughing. 'But for you she will not only understand, she will even approve. Thank you for your promise. I may well stand in need of it.'

'It is I who should thank you, General.'

Not many minutes later, Fournier-Sarlovèze was swaggering, hands in pockets, out of the front door of the Hôtel d'Asselnat under the bewildered and faintly shocked gaze of Jeremy, the butler, who, still only half-awake, regarded the officers of the law with a kind of scandalized disapproval. One of the men recovered the horse which Fournier, like the rest, had left outside the wall in the rue de l'Université and the general sprang into the saddle as lightly as if about to go on parade, then, turning, blew a kiss to Marianne who was standing on the steps:

'Au revoir, Princess Marianne. And do not let this worry you. You can't think how exhilarating it is to go to prison for the sake of a woman as lovely as you!'

The little cavalcade moved away into the dawn which was already beginning to touch the white stone face of the house with tones of rosy pink, while from the gardens all around came a faint freshness of rising mist and the first notes of birdsong. Marianne was deathly tired and her hip was hurting her atrociously. Behind her, her nightcapped servants, blinking sleepily, preserved a respectful silence. Only Gracchus, the last on the scene, barefooted and barechested, dared to ask his mistress: 'What is it? What has been happening, Miss M – Your Highness?'

'Nothing, Gracchus. Go and get dressed and put the horses to. I must go out. And you, Jeremy, you need not stand there gaping at me as if I were about to sentence you to death. Go and wake Agathe. If the house fell down about her ears that girl would sleep through it!'

'Wh-what shall I tell her?'

'Tell her you're a blockhead, Jeremy!' Marianne exclaimed exasperatedly. 'And that I shall dismiss you from my service if she is not in my room inside five minutes!'

Back in her own room once more, she anointed her burn with Balm of Peru and swallowed a large glass of cold water, without sparing a glance for the desolation of her once-charming bedchamber with its torn hangings and shattered porcelain. When the flustered Agathe came running in, she told her to go at once and make her some strong coffee but, instead of obeying, the girl stood in the doorway staring at the spectacle which met her eyes.

'Well?' Marianne said impatiently. 'Did you hear me?'

'Oh M-Madame!' Agathe managed to say at last. 'Who was it did this? It Hooks as if the d-devil himself had been here!'

Marianne gave a small, mirthless laugh and went to the wardrobe. 'You may well say so,' she remarked as she took down a dress at random. 'The devil in person – or rather in three persons! Now, my coffee, and hurry.'

Agathe departed precipitately.

CHAPTER FIVE

The House of the Gentle Shade

Sunset was lighting blood-red fires behind the hill of Chaillot as once again Marianne's chaise crossed the Pont de la Concorde en route for Passy. The coming darkness, brought on faster by the heavy clouds which had invaded the sky over Paris as the day wore on, seemed to be smothering the last red glow of the dying sun beneath a heavy grey blanket. The air was unbearably hot, clammy and oppressive, and little enough of it made its way through the open windows of the chaise to where Marianne sat stifling among the warm velvet cushions, scarcely able to breathe for the heat and the strain on her over-stretched nerves.

This was her second journey to Passy. When she had reached the house that morning, determined to see Jason, even if only for a moment, at the cost of whatever scene might be necessary, in order to warn him, she had found the house shuttered and closed. A Swiss porter in carpet slippers, grumpy and half-asleep, had appeared eventually in response to Gracchus's repeated summons on the bell and told them in his heavily accented French that there was no one at home. Mr and Mrs Beaufort were at Mortefontaine, having gone there straight from the theatre.[1] The sight of a gold coin did however induce the man to admit that the American was to return that evening. Marianne turned back, disappointed, sorry for once that she had not taken Francis's advice. But then, she had to admit, it was unlike him to be telling the truth.

Tired though she was as a result of her sleepless night and the pain of her injured side, which was making her slightly feverish, she was unable to rest. She had wandered about like a lost soul between her own room and the garden, and running into the salon a hundred times to look at the exquisitely decorated bronze enamelled clock there. The only event which occurred in the whole of that endless day was a visit from the police inspector who came to ask some embarrassed but persistent and distinctly leading questions concerning that morning's duel. Marianne had stuck to Fournier's story, that it had not been a duel, but the man had gone away visibly dissatisfied.

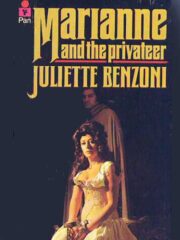

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.