At her side, in a tight-fitting uniform of green and gold, stiff with decorations, Chernychev surveyed the house arrogantly.

They were a striking couple. Talma, playing Nero, had just reached the lines:

'… so fair sight ravished mine eyes,

I tried to speak, but lo, my voice was dumb,

I stood unmoving, held in long amaze…'

The actor's voice died away and he stood, motionless in the centre of the stage, staring, while the audience, struck by the coincidence contained in the words, burst into spontaneous applause. Marianne, amused, smiled down at him and Talma stepped forward instantly, hand on heart, and bowed to the box as if it had contained the Empress herself. Then he turned to resume his interrupted dialogue with the actor playing Narcisse and Marianne and her escort took their seats at last.

But Marianne, who was still not fully recovered, had not come to the theatre that night for the pleasure of seeing the Empire's greatest tragic actor. She was looking round, her face partly screened by her fan, scrutinizing the house attentively in search of the face she had come there to find. The great Talma's performances were always well attended and Marianne had hinted discreetly to her friend Talleyrand that she would like him to invite the Beauforts to share his box for Britannicus.

There they were, in fact, in a box almost directly facing that occupied by Marianne herself. Pilar, looking more Spanish than ever in a gown of black lace, was sitting in front, next to the prince, who seemed to be dozing with his chin sunk in his cravat and both hands clasped on the knob of his stick. Jason was standing behind, one hand resting lightly on the back of Pilar's chair. The other occupants of the box were an elderly woman and a man evidently a good deal older still. The woman retained some traces of what must once have been quite remarkable beauty. Her bright, black eyes still held the fire of youth in them and the red bow of her lips revealed both sensuality and firmness. She, too, was dressed, severely but sumptuously, in black. The man, who was bald-headed except for some few remaining red hairs, had the flushed, slightly bloated complexion of one over-fond of the bottle, but despite his bowed shoulders it was clear that this man had once possessed strength and endurance above the average. He looked like nothing so much as an ancient, riven oak tree that still manages somehow to survive.

With the exception of Jason, who appeared absorbed in what was taking place on the stage, they were all looking at Marianne and her companion. Pilar had even invoked the assistance of a pair of lorgnettes, which she wielded with about as-much cordiality as if she had been looking down the barrel of a gun. Talleyrand smiled his habitual lazy smile, lifted his hand fractionally in greeting and appeared to fall asleep again, despite the efforts of his other neighbour, the black-eyed woman, who seemed to be bombarding him with questions about the new arrivals. Marianne heard Chernychev, at her side, give a soft, mirthless laugh:

'We would appear to have caused something of a stir…'

'It surprises you?'

'Not in the least.'

'You dislike it, then?'

This time, the Russian laughed outright. 'Dislike it? My dear Princess, you must know there is nothing I like better; except, of course, when it would conflict with my duty as an officer. But it's not merely a stir that I should like to make with you, it is a scandal.'

'A scandal! You must be mad!'

'By no means. I say: a scandal – so that you will be bound to me, irrevocably, for ever, with no possibility of escape.'

Underlying the lightness of his words there was a faint suggestion of a threat which shook Marianne. Her fan shut with a click.

'So,' she said slowly. 'This is the great love you have been pouring into my ears ever since our first meeting? You want to chain me to you, make me your private property – and guard me fiercely, I dare say? In other words, you would put me in prison…'

Chernychev showed his teeth in a smile which Marianne could not help comparing with that of a wild animal, but his voice, when he answered her, was smooth as silk:

'I am a Tartar, you know… Once, on the road to Samarkand, where the grass never grew again after it had been trampled down by the hordes of Genghis Khan, a poor camel-driver found the most beautiful emerald, dropped, probably, from some robber's hoard. He was poor, he was hungry and cold and to him the stone represented a great fortune. Yet, instead of selling it and living in ease and luxury, the poor camel-driver kept the emerald and hid it in the folds of his greasy turban, and from that day forth he neither hungered nor thirsted for he had lost the need for food or drink. All that mattered to him was the emerald. And so, in order to be sure that none should steal it from him, he travelled on, ever farther and farther into the desert, until he came to the deep, inaccessible caverns where there was nothing to look for but death. And death came, very slow and painful, but he watched it coming with a smile because he had the emerald pressed close to his heart…'

'A pretty story,' Marianne said coolly, 'and flattering in its implications, but really, my dear Count, I think I shall be very glad to see you go back to St Petersburg. As a friend, you are too dangerous by far!'

'You mistake me, Marianne. I am not your friend. I love you and I want you, that is all. And do not rejoice in my departure too soon – I shall return before long. In any case—'

He broke off. A chorus of indignant 'Sshs' was directed at them from all parts of the house while, from the stage, Talma was regarding them with deep reproach. Concealing a smile behind her fan, Marianne turned her attention to the play and Talma/Nero, satisfied, returned to his passionate scene with Junia:

'Ponder it, lady, weigh within your heart

This choice, meet guerdon for a prince that loves you,

Meet for your beauty, too long held in thrall,

Meet for that part which to the world you owe.'

Suddenly, the Russian chuckled under his breath. 'You hear? The piece could scarcely be more apt! You'd think that Nero must have heard me…'

Marianne only shrugged, conscious that the slightest retort would revive the argument and bring the wrath of the audience down on them again. But Racine had no power to interest her tonight and indeed it was not for Britannicus, nor even for Talma, that she had come to the theatre. She had come simply in order to see Jason and, more important, for him to see her. Her eyes resumed their discreet study of the house.

The Emperor and Empress had returned to Compiègne, so that few members of the court were present and the imperial box might well have been empty, but in fact it was occupied by Princess Pauline. Napoleon's youngest sister found the festivities at Compiègne little to her taste and much preferred to spend the summer at Neuilly, where her new chateau was on the point of completion. Tonight, she was radiant with happiness, with Metternich, very handsome in a dark blue coat which suited his slim build and fair hair perfectly, on one side of her and on the other a young German officer, Conrad Friedrich, known to be the latest lover of this most charming of the Bonapartes.

Apart from Marianne, the princess was the only woman present who had dared to disobey the Emperor's command. Her gown of snowy muslin, cut so low in front as to be scarcely decent, seemed to have been designed to reveal more than it concealed of her justly-famous form and to enhance the splendour of a magnificent set of turquoises of a deep and dazzling blue which were Napoleon's most recent gift to one who was not known for nothing as 'Our Lady of the Trinkets'.

Marianne was in no way surprised to see Pauline favour Chernychev with one of her brilliant smiles. The Tsar's dashing courier had long been intimate with the princess's boudoir. However, the smile did not linger but passed on to the stage, where Talma almost forgot a line from sheer rapture. Pauline was another who did not visit the theatre to see the play. She came to be admired and to enjoy the effect, always sufficiently gratifying, which her presence produced on the men in the audience.

Not far from the imperial box, Prince Cambacérès, huge and smothered as usual in gold-braid, slumbered in his seat, sunk in the pleasures of a good digestion, while next to him, Gaudin, Minister of Finance, elegant and old-fashioned at the same time in his coat of the latest cut and bob-wig, seemed to find his snuff-box infinitely more absorbing than what was going forward on the stage. In another, darkened box, Marianne caught sight of Fortunée Hamelin, deep in whispered conversation with an unidentifiable hussar who, in turn, was attracting apparently idle but actually extremely penetrating glances from the exquisite Madame Récamier. Next door, in the quartermaster-general's box, his wife, the beautiful Countess Daru, in a gown of peacock blue satin, was sitting dreamily beside her cousin, a young civil servant by the name of Henri Beyle with a broad, plain face redeemed from the commonplace by a magnificent brow, a bright and piercing eye and a sardonic curve of the lips. Finally, in a large centre box, Marshal Berthier, Prince of Wagram, sat dividing his attentions between his wife, a homely and good-humoured Bavarian princess, and his mistress, the tempestuous, wickedly sharp-tongued and grossly overweight Marchesa Visconti whose long-standing liaison with him was a source of never-failing irritation to Napoleon. Of the remainder of the audience, a great many were strangers to Marianne; Austrians, Poles, Russians and Germans who had come to Paris to attend the wedding celebrations and at least half of whom clearly had not the faintest comprehension of Racine. Among them, the palm of beauty undoubtedly belonged to the dazzling Countess Atocka, handsome Flahaut's latest conquest. These two were sitting in a box discreetly to one side, she radiant, he still a little pale from his recent illness, but neither with eyes for anything but each other.

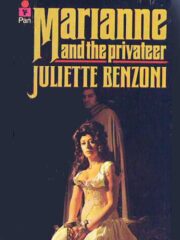

"Marianne and the Privateer" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and the Privateer". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and the Privateer" друзьям в соцсетях.