The last words were addressed, of course, to Marianne who, oblivious of the gallantry implied, did not even remember to thank him. One thing only had she grasped from what the Austrian had said and the question it raised in her mind impelled her to ask:

'Their majesties have retired? Does that mean – but surely —' The words died on her lips, but Clary was laughing again.

'I fear it does. It appears that the Emperor's first action was to inquire of his uncle, Cardinal Fesch, if he were truly married – that is, whether the proxy wedding in Vienna made the Archduchess lawfully his wife.'

'And?' Marianne's throat was dry.

'And the Emperor informed the – the Empress that he would shortly do himself the honour of visiting her in her apartments. He merely wanted time to take a bath.'

Every vestige of colour drained from Marianne's face.

'So —' Her voice was so hoarse that the Austrian glanced at her with surprise and Arcadius with alarm.

'So their majesties retired and I promptly came here to your service, madame – but how pale you are! You are not ill? You, Robineau, let your wife at once conduct this lady to my own room, it is the best in the house… Good God!'

This last exclamation was caused by Marianne who, drained of her last ounce of strength by the blow which he had unwittingly dealt her, had suddenly swayed and would have fallen if Jolival had not caught her in time. A moment later, carried by Clary and preceded by Madame Robineau in a starched muslin cap and armed with a large brass candlestick, Marianne ascended the well-polished staircase of the Grand-Cerf in a state of total unconsciousness.

When, some fifteen minutes later, she emerged from this blissful state, Marianne found herself looking at two faces side by side. One was Arcadius's mouse-like countenance, the other, which was highly-coloured and surmounted by a lofty cap from which some wisps of brown hair escaped, belonged to a woman. Seeing that Marianne had opened her eyes, the woman ceased bathing her temples with vinegar and observed with satisfaction that 'that was better now'.

To Marianne it did not seem in the least better, worse if anything. She was frozen to the marrow yet every now and then she felt bathed in great waves of heat, her teeth were chattering and there was a vice tightening on her head. Even so, the returning memory of what she had heard was enough to make her try and spring up from the bed where they had laid her fully dressed.

'I must go!' she said, trembling so much as she spoke that she could hardly get the words out. 'I want to go home, at once!'

Arcadius put both hands on her shoulders and forced her to lie down again.

'Out of the question. Ride back to Paris in this weather? It would be the death of you, my dear. I am no doctor but I know a little of the subject. I can tell from your flushed cheeks that you have a temperature —'

'What does that matter? I cannot stay here! Can't you hear it – the music, the singing, the fireworks? Can't you hear the whole city going mad with joy because the Emperor has bedded the daughter of his greatest enemy?'

'Marianne, I beg you —' Arcadius was looking at her haggard face in alarm.

Marianne gave a strident peal of laughter that was painful to hear. Brushing Arcadius aside, she jumped off the bed and ran to the window. With a furious gesture she flung back the curtain and stood holding on to it, looking out at the brightly-lit palace which stared challengingly back across the wet and empty square. Inside that building Napoleon was holding that Austrian woman in his arms, possessing her as he had possessed Marianne, murmuring perhaps the self-same words of love… Rage and jealousy combined with the fever in her already burning head to torment her with the flames of hell. Her memory recalled with ruthless clarity all her lover's ways, the way he looked – oh, if she could only see through those bland, white walls, if she could only know which of those shuttered windows hid that betrayal of love in which Marianne's own heart was the victim!

'Mio dolce amore —' she muttered through clenched teeth. 'Mio dolce amore! Is he saying that to her, too?'

Arcadius had not dared to go to her or touch her, fearing that in her delirium she would begin to scream aloud. Now he spoke softly to the horrified landlady.

'She is very ill. Fetch a doctor, quickly.'

The woman did not need telling twice. She whisked herself off down the passage in a flurry of starched petticoats while very quietly, one step at a time, Jolival approached Marianne. She did not even see him. Standing taut as a bowstring, and staring with dilated eyes at the great, white building, it seemed to her suddenly as if the walls were made of glass, enabling her to see right into that inner room where, beneath a canopy of gold and purple velvet, an ivory body lay embracing another whose plump flesh was overlaid with tints of rose. In that moment of crucified agony, nothing existed for Marianne save the picture of a love scene which her imagination conjured up the more vividly because the reality had so often been hers, Arcadius, standing within an arm's length of her, heard her murmur:

'How can you kiss her as you kissed me? Yet, the lips are your own. Have you forgotten indeed? You cannot – you cannot love her as you loved me. Oh no, I implore you – do not hold her so close! Let her go... She will bring you bad luck, I know it. I can tell. Remember how the wheel broke on the steps of the wayside shrine. You cannot love her – no, no – NO!'

She uttered one, brief, heartbroken cry, then sank to her knees beside the window, racked by shuddering sobs. Even so, the tears released the nervous tension which had so alarmed Arcadius so that now he found himself trembling with relief.

Realizing that he might safely touch her now, he bent and reached out with infinite tenderness to raise her to her feet. Hardly daring to hold the slender form that trembled against his shoulder, he guided her faltering steps towards the bed. She did not resist but suffered herself to be led like a little child, too deep in her own misery to be aware of what was happening. By the time Jolival had her lying on the bed once more, the door had opened to admit Madame Robineau with the doctor. That this should be none other than Corvisart, Napoleon's own doctor, did not surprise Arcadius in the least. After the events of that day, nothing would have had the power to surprise him. None the less, it was a remarkable comfort.

'I was downstairs,' he said, 'sharing a bowl of punch with some friends, when I heard madame here calling for a doctor. Prince Clary was hard on her heels, bombarding her with questions, and it was he who informed me of the invalid's identity. May I ask what the Signorina Maria Stella is doing here and in this condition?'

Frowning severely at the still-sobbing Marianne, the doctor folded his arms and his black-dad bulk seemed to tower over Arcadius. Jolival made a helpless gesture.

'She is your patient,' he said, 'and you must know her a little. She was set on coming —'

'You should not have let her.'

'I'd have liked to see you try and stop her. Do you know, we followed the Archduchess's convoy from the other side of Soissons? When Marianne heard what had happened at the palace, her feelings overcame her.'

'All that way in the pouring rain! It was madness. As for what happened at the palace, that was nothing to go into convulsions over. Good lord, to throw a fit because his majesty was in haste to see what kind of a bargain he had got!'

While the two men were talking, Madame Robineau, with the help of a maidservant, had been expeditiously undressing Marianne, now quiet as a baby, and tucking her into the big bed which the maid had warmed hastily with a copper warming-pan. The girl's sobs were quieter now although she was growing increasingly feverish. Her mind seemed calmer, however, and the violent outburst of grief which had shaken her had done something to relieve the worst tension, so that she was able to listen almost with indifference to Corvisart's rumbling voice berating her on the imprudence of riding about in the icy rain.

'You have a carriage, I think, and some very fine horses? What made you go on horseback in this weather?'

'I like riding,' Marianne said obstinately, determined to reveal nothing of her real motives.

The doctor snorted, 'And what do you think the Emperor will say when he hears what you have been up to, eh?'

Marianne's hand emerged swiftly from the bedclothes and was laid on Corvisart's.

'But he will not hear. Doctor, please say nothing to him! Besides – I dare say he will not be interested.'

Corvisart gave a mighty roar of laughter.

'I see. You do not wish the Emperor to know but if you could be sure it would make him very angry to hear what you have been doing, you would send me to him straight away, is that it? Well then, you may be happy: I will tell him and he will be furious.'

'I don't believe you,' Marianne said bitterly. The Emperor is —'

'The Emperor is busy trying to get himself an heir,' the doctor interrupted her ruthlessly. 'My dear girl, I find you quite incomprehensible. You must have known that this was inevitable – that it was the Emperor's sole purpose in marrying.'

'He need not have been in such a hurry! Why tonight —'

'Why take the Archduchess into his bed tonight?' Corvisart seemed bent on finishing her sentences for her. 'Because he is in a hurry, of course. He is married, he wants an heir, he sets about the business right away. What could be more natural?'

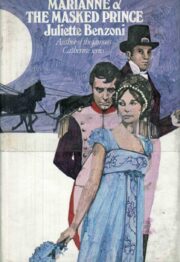

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.