In an instant, Napoleon had joined him, while Marianne, drawn by a curiosity she could not help, crept forward into the church doorway. She was in no danger of being seen. The Emperor's attention was all on the long string of carriages now coming at a smart pace down the road towards them, led by a mounted escort in colours of blue and mauve. Marianne could feel the tension in him from where she stood, and it came to her suddenly how much it meant to him, the arrival of this daughter of the Habsburgs to whom he looked for his heir and through whom he would ally himself at last with the blood royal of Europe. To fight back her growing anguish, she strove to remember his contemptuous words: 'I am marrying a womb.' It was no good. Everything in her lover's attitude (gossip even said that he had insisted on learning to dance in his new bride's honour) betrayed how impatiently he had been waiting for the moment when his future wife would come to him. Even this schoolboy prank in which he had indulged in the company of his brother-in-law! He could not bear to wait for the next day's official, ceremonial meeting at Pontarcher.

Napoleon stood in the centre of the road and the hussars were already reining in their mounts at the sight of his familiar figure, crying: 'The Emperor! It is the Emperor!' The words were echoed a moment later by the chamberlain, M. de Seyssel, who came riding up, but Napoleon ignored them all. Oblivious of the driving rain, he was running towards the big coach drawn by eight steaming horses and tugging open the door without waiting for it to be opened for him. Marianne caught a glimpse of two women inside before one leaned forward and exclaimed: 'His majesty, the Emperor!'

But Napoleon, it was clear, had eyes only for her companion, a tall, fair girl with a pink and white complexion and round, somewhat protuberant blue eyes, now bulging more than usual with alarm. Her pouting lips were trembling as she tried to smile. She was dressed in a plain green velvet cloak but on her head she wore a startling confection of multicoloured feathers that resembled the crest of a moulting parrot.

Marianne, standing a few yards away devouring the Archduchess with her eyes, experienced a fierce spasm of joy at the realization that Marie-Louise, if not precisely ugly, was certainly no more than passable. Her complexion was good enough but her blue eyes held no intelligence and the famous Habsburg lip combined with an overlong nose to produce a face lacking in charm. And then she was so badly dressed! She was fat, too, too fat for a young girl: in ten years she would be gross. Already there was a heaviness about her.

Eagerly, Marianne looked at the Emperor who was standing with his feet in a puddle gazing at his future wife, trying to gauge his reactions. Surely, he must be disappointed. He would bow formally, kiss his bride's hand and then return to his own carriage which was already undergoing repairs — but no, his voice rang out gaily:

'Madame, I am delighted to see you!'

Oblivious of his drenched clothes, he sprang into the coach and caught the fair girl in his arms, kissing her several times with an enthusiasm that drew a prim smile from the other occupant of the vehicle, a pretty, blonde woman whose pearly skin and dimpled charms were not destroyed by the fact that her face was over-fleshed and her neck too short. The innocence of her expression was belied by a sardonic glint in her eye which Marianne did not quite like. This must be Napoleon's sister, Caroline Murat, one of the most notorious harpies in court circles. Her husband, having first kissed the Archduchess's hand, returned alone to the plain travelling coach while Napoleon settled himself in the seat facing the two women and addressed the coachman who still stood beside the vehicle with a beaming smile.

'Drive on to Compiègne, and don't spare the horses!'

'But sire,' the Queen of Naples murmured protestingly, 'we are expected at Soissons. There is to be a supper, a reception.'

'Then they can eat their supper without us. It is my wish that my lady wife spend tonight in her own house! Drive on.'

Caroline's lips tightened at the snub but she retired into her corner and the carriage moved off, affording Marianne a last glimpse through her tears of Napoleon smiling blissfully at his bride. A shout of command and the escort quickened their pace to a trot. One by one, the eighty-three vehicles of the new Empress's train moved past the church. Marianne stood leaning on the wet stones of the Gothic porch and watched them unseeingly, so deep in her own miserable thoughts that Arcadius had at last to shake her gently to rouse her.

'What now?' he asked. We ought to go straight back to the inn. You are soaked to the skin, and so am I.'

Marianne looked at him strangely.

'We are going to Compiègne…'

'What for?' Jolival sounded suspicious. 'You're up to some foolishness, I don't doubt. What can you do in all this?'

Marianne stamped her foot. 'I wish to go to Compiègne, I tell you. Don't ask me why because I don't know. All I know is that I have to go there.'

She was so pale that Arcadius frowned. All the life seemed to have drained from her, leaving only a mechanical creature. In an effort to rouse her from her frozen stupor, he objected wildly: 'But what about the rendezvous tonight?'

'That no longer concerns me. He did not make it. Surely you heard? He is going to Compiègne. He does not mean to return to this place. How far are we from Compiègne?'

'About forty miles.'

'You see! To horse, and fast. I want to be there before them.'

As she spoke, she was running towards the trees where they had tethered the horses. Hard on her heels, Arcadius persisted in trying to make her see reason.

'Don't be a fool, Marianne. Come back to Braine and let me go and see who is waiting for you tonight.'

'That does not concern me, I tell you. When will you understand that there is only one person in the world I care about? Besides, it is bound to be a trap. I am certain of that now… But I do not ask you to come with me,' she added cruelly. 'I can very well go alone.'

'Don't talk nonsense.' Arcadius shrugged and cupped his hands to throw her into the saddle. He did not blame her for her ill-temper because he knew what she was suffering at that moment, but it grieved him to see her punishing herself in a situation which she was powerless to alter.

He merely said: 'Very well, let's go if you insist.' Then he sought his own mount.

Without answering, Marianne dug her heels into her horse's sides and the creature shot off, making for the little track along the river. The few people who had emerged to witness the scene went back indoors and Courcelles sank back into its accustomed quiet. The damaged coach, provided with a fresh wheel by the local wheelwright, had also disappeared.

Although it had the advantage of them by several minutes, Marianne and Arcadius emerged on to the main highway at Soissons in time to see the imperial coach pass by at the head of the column, having thundered through the town before the shocked and astonished eyes of the Sous-Préfet, the town council and the military who had waited for hours in the pouring rain merely to have the pleasure of seeing their Emperor dash away under their noses.

'Why is he in such a hurry ?' Marianne muttered through clenched teeth. Why does he have to be in Compiègne tonight?'

She was swinging into the saddle again after a change of horses at the Hôtel des Postes when she saw the imperial carriage come to a sudden stop. The door opened and the Queen of Naples, recognizable to Marianne by the pink and mauve ostrich feathers adorning her pearl-grey bonnet, stepped out into the road and marched with an air of offended dignity towards the second coach, the chamberlain trotting at her heels. The steps were let down and, like a queen going into exile, she disappeared within and the procession continued on its way.

Marianne looked inquiringly at Arcadius. What was that about?'

Arcadius was bending over his horse's neck, apparently having some trouble with the bit, and did not answer. Irritated by his silence, Marianne burst out: 'Have the courage to tell me the truth at least, Arcadius! Do you think he wants to be alone with that woman?'

'It is possible,' Jolival conceded cautiously. 'Unless the Queen of Naples has been indulging in one of her unfortunate fits of ill-humour —'

'In the Emperor's presence? Unlikely, I think. Ride fast, my friend. I want to be there when they alight from that coach.'

The mad career began again, splashing through icy puddles, brushing aside the low branches that obscured the unfrequented ways.

It was dark by the time they entered Compiègne and Marianne's teeth were chattering with cold and exhaustion. She kept herself in the saddle only by a prodigious effort of will. Her whole body ached as if she had been thrashed. Even so, they were only moments ahead of the cortege; the rumble of the eighty-three vehicles had never been out of earshot on that endless ride except at moments when they had plunged deep into woods far off the road.

Now, riding through the brightly-lit streets, decorated from top to bottom, Marianne blinked like a night-bird caught suddenly in the light. The rain had stopped. The news had run through Compiègne that the Emperor was bringing home his bride that very night instead of on the morrow as expected, and in spite of the darkness and the weather all the inhabitants were out in the streets or in the inns. Already a large crowd had gathered outside the railings of the big white palace.

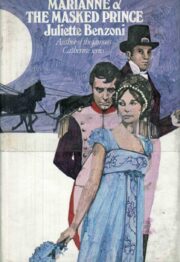

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.