She swung round but saw only the other mirrors on the wall reflecting nothing but the quiet candlelight. There was no one in the room. Yet Marianne could have sworn that it was Matteo Damiani who had been there, watching her with lustful eyes as she undressed. But there was nothing there. The silence was absolute. Not a sound, not a breath.

Her legs felt weak and she subsided on to the brocade-covered stool that stood before the dressing-table and passed a trembling hand across her face. Had it been an hallucination? Had the steward made such an impression on her that she was beginning to see him everywhere? Or was it simply fatigue? She could no longer be quite sure that she had really seen him. She had heard that nerves strained to breaking point could conjure up phantoms, bring forms and faces into being where none existed.

Dona Lavinia returned to find her lying on the stool, half-naked and white as a sheet. She wrung her hands agitatedly.

'Your highness should not have done it,' she exclaimed reproachfully. 'Why did you not wait for me? See, you are trembling all over. You are not ill?'

'No, just exhausted, Dona Lavinia. I can't wait to get into bed, and sleep. Won't you give me some of whatever it was you gave to Agathe? I want to be sure to sleep well.'

'It's only natural after such a day.'

In a very few moments, Marianne was lying in bed while Dona Lavinia brought her a warm tisane, its pleasant scent already beginning to relax her tired nerves. She drank it gratefully, longing to escape from her wild imaginings. She was sure that, without some outside aid, she would never manage to get to sleep, however tired she was, while she could still see that face. As though guessing something of her trouble, Dona Lavinia sat down on a chair near the bed.

'I will stay here until your highness is asleep,' she promised, 'and be sure that nothing disturbs you.'

Relieved, although she would not admit it, of a weight on her mind, Marianne closed her eyes and let the tisane take its soothing effect. Within minutes, she was fast asleep.

Dona Lavinia sat still in her chair. She had taken a set of ivory beads from her pocket and was quietly saying her prayers. Quite suddenly, there came a sound of horses' hooves galloping in the darkness, softly at first, then growing louder. The housekeeper rose noiselessly and went to the window, pulling one of the curtains a little aside. Outside, in the thick darkness, a white shape appeared, moved swiftly across the grass and vanished as fast as it had come: a white horse going at full gallop, bearing a dark figure on its back.

Dona Lavinia let fall the curtain with a sigh and returned to her place at Marianne's bedside. She felt no desire for sleep. On this night, more than any other, she felt the need to pray, both for the sleeper in the room and for that other whom she loved like her own child; if happiness were impossible, she prayed that heaven would grant them at least the gentle numbness of peace.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Night of Enchantment

When Marianne awoke after a night's uninterrupted slumber to a room flooded with brilliant sunshine, she was fully herself again. The previous night's storm had washed everything clean and such debris of broken branches and wind-tossed leaves as it had left about the park had been already swept up by the gardeners of the villa. Grass and trees put forth their brightest green and all the sweet fresh smells of the warm countryside were wafted in at the open windows, bringing the mingled scents of hay and honey-suckle, cypress and rosemary.

Just as when she closed her eyes, she opened them to find Dona Lavinia standing by her bedside, smilingly arranging a huge armful of roses in a pair of tall vases.

'His highness desired that the first thing you saw this morning should be the loveliest of all flowers.' She hesitated. There is this, also.'

'This' was a sandalwood box and a number of black leather cases stamped with the arms of Sant'Anna but all bearing the unmistakable signs of wear inseparable from old things.

'What are they?' Marianne asked.

The jewels of the princesses of Sant'Anna, my lady. Those which belonged to Dona Adriana, our Prince's mother, and – and those of the other princesses. Some of them are very old.'

There was, in fact, jewellery of every description, from ancient and very lovely cameos to an assortment of curious oriental objects, but the greater part was made up of heavy renaissance ornaments, huge baroque pearls made to look like sirens and centaurs in settings of multicoloured gems. There was jewellery of more modern workmanship also; ropes of diamonds to adorn a décolletage, dusters of brilliants, collars and necklaces of gold and precious stones. There was also a number of unset stones and when Marianne had examined everything, Dona Lavinia produced a small silver casket lined with black velvet on which reposed twelve incomparable emeralds. They were huge, rough-cut stones of a deep, translucent green and intense luminosity, certainly the finest Marianne had ever seen. Even those which Napoleon had given her could not begin to match their beauty. And suddenly, the housekeeper echoed the Emperor's words.

'His highness said that they were the same green as my lady's eyes. His grandfather, Prince Sebastiano, brought them back from Peru for his wife, but she did not care for the stones.'

'Why ever not?' Marianne was holding the perfect gems up to watch the play of light upon them. 'They are beautiful!'

'They were thought in earlier times to be a symbol of peace and love. Dona Lucinda believed in love – but she hated peace.'

So it was that Marianne heard for the first time the name of the woman who had been so enamoured of her own reflection that she had covered the walls of her room with mirrors. But there was no time to ask more. Dona Lavinia informed her with a curtsey that her bath was prepared and the cardinal awaited her company at breakfast. Before the new Princess could summon up courage to ask her to stay and answer her questions, she had gone, leaving her to Agathe's ministrations. A shadow had undoubtedly passed over the old woman's face, a faint darkening of her eyes as if she regretted having uttered that name, and she had certainly been in a hurry to be gone. Clearly, she was anxious to avoid the questions that she sensed were coming.

When Marianne joined her godfather in the library, where he had ordered breakfast to be served, she lost no time in asking the question which had put Dona Lavinia to flight. She began by describing how she had been presented with the ancestral jewels.

'Who was the Prince's grandmother? I gather that her name was Lucinda but no one seems anxious to talk about her. Do you know why?'

The cardinal spread a thick layer of delicious-smelling tomato sauce over his pasta then added cheese and mixed the whole carefully together. At length, having tasted the resultant combination, he said coolly: 'No. I have no idea.'

'Oh come, that is surely impossible! I know you have been acquainted with the Sant'Annas for ever. Otherwise how does it come about that you are permitted to share the secret which surrounds Prince Corrado? You must know something of this Lucinda. Say, rather, that you will not tell me.'

The cardinal chuckled. 'You are longing to know so much that in a moment you will be calling me a liar,' he said. 'Well, my dear, let me tell you that a prince of the Church does not tell lies, or at least, no more than a simple parish priest. It is quite true that I know very little, beyond the fact that she was a Venetian, of the noble family of Soranzo, and extremely beautiful.'

'Hence the mirrors! But the mere fact of being beautiful and over-fond of her own reflection does not explain the kind of reserve which everyone here seems to feel with regard to her. Even her portrait seems to have vanished.'

'I should add that, by what I have heard, Dona Lucinda's reputation was – er – unsavoury. There are those among the few people still alive who knew her who claim that she was mad, others say that she was something of a witch, or at least in league with the devil. Such things do not make for popularity here – or elsewhere.'

Marianne had an idea that the cardinal was being deliberately evasive. For all the trust and respect in which she held her godfather, she could not help having an odd suspicion that he was not telling her the truth, or at any rate not the whole truth. Determined, however, to drive him as far as possible, she asked innocently, while pretending to be absorbed in the selection of cherries from a basket of fruit: 'Where is she buried? In the chapel?'

The cardinal choked as if he had swallowed a mouthful the wrong way but it seemed to Marianne that his subsequent fit of coughing was not altogether accidental and that it was designed to cover up the sudden flush which coloured his cheeks. However, she smiled prettily and offered him a glass of water.

'Drink this. It will help.'

'Thank you. Her grave – hmm – no, there is not one.'

'No grave?'

'No. Lucinda died tragically in a fire. Her body was never recovered. No doubt there is, somewhere in the chapel, an inscription – er – commemorating the fact. Now, do you care to step outside and take a look at your new estate? The weather is perfect and the park is looking its best. There are the stables, too. You will certainly be impressed by them. You used to be so fond of horses as a child. Did you know that the animals here are of the same stock as those in the famous Imperial Riding School in Vienna? They are Lipizzaners. The Archduke Charles, who founded the famous stud at Lipizza in 1580, presented the Sant'Anna of the period with a stallion and two mares. Ever since then, the princes of this house have devoted themselves to the perfecting of the breed.'

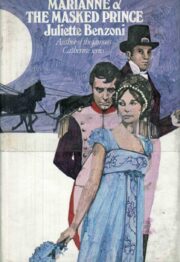

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.