With a weary sigh, Marianne allowed herself to be led to the place prepared for her. Close by, a huge white wax candle burned in a silver sconce standing on the floor but, apart from the sacred vessels and the altar cloth, no other preparations had been made for the ceremony. The little chapel was cold and damp, with the musty smell of buildings that are never aired. Along tie walls of the nave, long dead Sant'Annas slept in effigies of stone upon their ancient tombs. It was a cheerless place and Marianne was reminded of a play she had seen once, in London, in which the hero, under sentence of death, was allowed to marry the heroine in the prison chapel on the night before his execution. There, too, the prisoner had been separated from his bride by an iron grating, and Marianne recalled how vividly the sombre and dramatic scene had impressed her. Now she herself was to play the part of the bride and the union to be solemnized here would be just as brief. When they left the chapel they would be divided as surely as if the executioner's axe were to fall on one of them. Indeed, the man waiting silently behind the frail wall of velvet was also under sentence in his way. His youth sentenced him to Life, when life was an abomination.

The cardinal and the witnesses had taken their places a little way behind but Marianne saw to her surprise that Matteo Damiani had gone to the altar to assist the priest. He was now wearing a white surplice over his massive shoulders from which his bull neck emerged with a plebeian strength in curious contrast to certain traits of nobility in his features. It was a Roman face, beyond a doubt, but not a handsome one: perhaps it was the mouth that was too full, too heavily sensual, or the eyes, fixed and unblinking, whose gaze so soon became an intolerable burden. All through the service, Marianne was conscious of those eyes on her and when at last she turned on him a glance sparkling with anger and disdain the steward's bold stare did not waver and it seemed to her that there was even a cold, fleeting smile on his ugly lips. It so enraged her that for a moment she forgot the man who stood on the other side of the curtain, so near and yet so far away.

Never in her life had she given so little of her attention to the mass. Her whole being was taken up with the already familiar voice which she now heard praying almost uninterruptedly, praying aloud with a fervour and devotion that she found strangely disturbing. It had not occurred to her that the master of a domain of such sensual beauty could be the ardent Christian those prayers revealed. She had never heard such an agonizing combination of melancholy resignation and entreaty on any human lips. Surely, such prayers belonged only to the most strictly enclosed orders, places where the pitiless monastic rule foreshadowed the final annihilation of the grave? Little by little, she forgot Matteo Damiani in listening to that astonishing voice.

The time for the marriage vows had come. The chaplain descended the two stone steps and stood before the strange couple. As if in a dream, Marianne heard him put the ritual question to the Prince and in a moment the voice answered him with unexpected strength.

'In the sight of God and of men, I, Corrado, Prince of Sant'Anna, do here take as my lawful wedded wife…'

The sacred words rang out like a challenge, filling Marianne's ears like the rumble of a storm, and they were given a sinister emphasis by the violent clap of thunder which just then burst directly over the chapel. She blenched as if struck by a premonition of disaster and her own voice shook when her turn came to utter the formal vows. Then the priest said quietly: 'Join your hands.'

The black curtains parted. Wide-eyed Marianne saw a black velvet sleeve, a lace cuff and a hand, gloved in white kid, extended towards her. It was a very large hand, strong and long-fingered, and the glove moulded it perfectly: the hand of a very tall and active man. Trembling suddenly at this real, tangible object Marianne stared, fascinated, not daring to place her own within it. There was something about that open palm, those extended fingers, which was both attractive and alarming. It was like a trap.

'You must place your hand in his,' whispered the cardinal's voice in her ear.

All eyes were on her. Father Amundi's held surprise, the cardinal's a mixture of command and entreaty, Matteo Damiani's were sardonic. It may have been the last which decided her. She placed her hand firmly in the one held out to receive it. The fingers closed on it gently, almost delicately, as if they feared to hurt her. Marianne felt, through the glove, the firm, living warmth of the flesh. The words she had heard so short a time before came back to her.

'We shall never be as close again,' the voice had said.

Now, the old priest was pronouncing the final blessing, the words half drowned by a second peal of thunder.

'I declare you man and wife, for better for worse, until death do you part.'

Marianne felt the hand that held hers quiver. Another hand appeared through the crack in the curtains, for just long enough to slip a broad gold band on her finger, then both hands were withdrawn, taking hers with them. A tremor ran through her. Two lips were pressed to her fingertips before her hand was released.

The brief, physical link was broken. There was nothing behind the wall of velvet, only a sigh. Father Amundi kneeled in prayer at the altar, his back beneath his chasuble so bent that he looked like a bundle of cloth, reflecting the light from its folds. Another thunderclap, more violent than either of the two preceding ones, made the very walls reverberate with the din. At that moment, the heavens opened. Water poured down, drumming on the roof like a cataract. Within seconds, the chapel and those inside it had become an enclosed world, cut off by the storm. The old priest trotted away to the tiny sacristy, bearing the altar vessels, but Matteo almost flung off his surplice.

'A carriage must be fetched!' he exclaimed. The princess cannot return to the villa in this.'

He was already making for the door when Gracchus suggested diffidently: 'May I come with you, to help?'

The steward looked at him. 'There are plenty of servants to do that, and you are not familiar with our horses. Stay here.'

Beckoning authoritatively to two of the servants who had carried the torches, he opened the door and plunged out, head down, into the storm, hurling himself into the wind like a charging bull. After one bewildered glance at the black curtains, behind which there was now no sound of movement, as if the Prince had vanished miraculously into thin air, Marianne sought refuge beside her godfather. This sudden storm, breaking out at the very moment of her marriage, was more than she could bear.

'It is an omen,' she breathed. 'An evil omen.'

'Have you grown superstitious now?' he scolded her in an undertone. This was not the way you were brought up. I suppose you have caught this from the Corsican? They say he is inordinately superstitious.'

She recoiled before his ill-concealed anger. She could think of no reason for it, unless it was that he too had been struck by the storm and was trying to counteract his own feelings. He might have hoped to crush Marianne's childish fears beneath his own adult contempt but the result he achieved was quite different. The reminder of Napoleon was a salutary one for Marianne. It was as if the all-powerful Corsican had suddenly come into the chapel with his eagle eye and that unyielding hardness against which even the strongest broke themselves in vain. She heard his mocking laughter and the evil spell was broken. It was for his sake that she had been forced to accept this curious marriage, for the sake of the child that he had given her. Very soon, tomorrow, she would set out again for France, to him, and all this would be no more than a bad dream.

In a few minutes, Matteo reappeared. Without a word, but with a gesture so full of pride that it dared her to refuse him, he offered his hand to Marianne to lead her to the carriage. But she ignored him and, with an icy stare, made her own way to the door. She had entered the chapel on her godfather's arm: since there was no husband there to give her his arm, she intended to leave it alone. This man with his bold stare must learn to know that from now on she meant to be treated as sovereign mistress here.

Outside, the carriage was waiting with the steps already let down and the door held open by an expressionless and dripping lackey. But between it and the little porch stretched a large puddle, fed by a heavy curtain of water. Marianne swept the train of her precious gown over her arm.

'If your highness permits…' said a voice. Before she could utter a word of protest, Matteo had picked her up bodily in his arms and lifted her over the obstacle. She gave one squeak and then stiffened, shrinking from the hateful touch of his broad hands damped firmly round her thighs and under her arms, but his grip only tightened.

'Your highness should take care,' he said blandly. 'Your highness might fall in the mud.'

Marianne was obliged to let him place her on the cushioned seat of the carriage but she had hated feeling herself, even for an instant, pressed to that man's chest and she merely thanked him curtly, without a single glance. Not even the sight of the little cardinal, all bundled up in his red robes, being transported in the same fashion had the power to erase the angry frown from her brow.

'Tomorrow,' she said through her teeth, as soon as he was set down beside her, 'I am going home!'

'So soon? Is that not a little – hasty? I should have thought that you owed it to – to your husband, and the consideration he has shown you, to remain for, shall we say, a week, at least?'

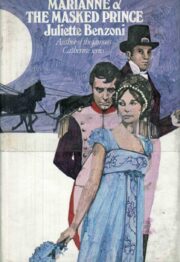

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.