'Si, si ... molto bene! If the signorina will condescend to follow me. Signor Zecchini has been waiting since this morning.'

Marianne accepted this without a blink although the name was perfectly unknown to her. Some messenger of the cardinal's perhaps? It could scarcely be the man she was to marry. She gestured towards the uniformed figures that were visible through the smoky kitchen windows.

'The inn appears to be very full?' she said.

Signor Orlandi shrugged his fat shoulders and spat on the ground to show his contempt for the military.

'Pah! The men belong to her highness, the Grand Duchess. They make only a brief stay – or so I trust!'

'Manoeuvres, no doubt?'

Orlandi's round face, to which a flowing moustache like a Calabrian bandit's attempted unsuccessfully to impart a touch of ferocity, seemed to lengthen strangely.

'The Emperor has given orders for the closing of all religious houses throughout Tuscany. Some bishops of Trasimene have rebelled against authority. Four have been apprehended but it is thought that the others have fled into Tuscany. This is the result…'

The same old story of the antagonism between Napoleon and the Pope! Marianne frowned. Why had her godfather brought her into these parts where the feud between Napoleon and the Church seemed hottest? It would scarcely lessen the difficulties she foresaw attending her journey back to Paris. Even now, she could not think without a shudder of what the Emperor's reaction would be when he learned that, without even consulting him, she had given herself in marriage to a stranger. The cardinal had certainly promised that the man would not be an enemy, the reverse indeed, but could anyone foresee the reactions of a man who was so obsessively jealous of his power?

Noise struck them in the face as they entered the main room of the inn. A group of officers were crowding round one of their number who had clearly just arrived. He was dusty and red-faced, his moustaches quivering with anger, and his eyes flashed as he spoke: ' – a damned, cold-blooded fellow of a servant came and shouted through the bars, above the barking of the dogs, that his master never received visitors and it was no use looking for those confounded bishops in his house. And with that he simply turned his back on me and walked off just as if we were not there! I'd not enough men with me to surround the place but damn me if they'll get away with this! Come on, to horse. We'll show this Sant'Anna what he'll get for defying the Emperor and her Imperial Highness the Grand Duchess.'

This martial declaration was greeted with a chorus of approval.

Orlandi had turned pale. 'If the signorina will be kind enough to wait a moment,' he whispered hurriedly, 'I must interfere. Ho there, Signor Officer!'

'What d'you want with me?' growled the angry man. 'Fetch me a carafe of chianti and sharp! I've a thirst on me that won't wait!'

But Orlandi, instead of complying, shook his head.

'Forgive me saying so but, if I were you, signor, I should not try to see Prince Sant'Anna. In the first place you will not succeed, and in the second, her highness will be displeased.'

The noise ceased abruptly. The officer thrust aside his comrades and came towards Orlandi. Marianne shrank back into the shadow of the stairs to avoid notice.

'What do you mean by that? Why should I not succeed?'

'Because no one has ever done so. Anyone in Lucca will tell you the same. It is known that Prince Sant'Anna exists, but no one has ever seen him, no one but the two or three servants closest to him. Not one of the others, and there are many, here and in the prince's other houses, have ever seen more than a figure in the distance. Never a face or a look. All they know of him is the sound of his voice.'

'He is hiding!' roared the captain. 'And why should he hide, eh, innkeeper? Do you know why he hides? If you don't know, I will tell you, because I shall know soon enough.'

'No, Signor Officer, you will not know, or expect to feel the anger of the Grand Duchess Elisa, for she, like the Grand Dukes before her, has always respected the Prince's wish for seclusion.'

The soldier gave a shout of laughter but to Marianne, listening eagerly to this strange story, his laugh rang false.

'Is that so? Is he the devil, then, your Prince?'

Orlandi shivered superstitiously and crossed himself hurriedly several times while one hand behind his back, where the officer could not see it, pointed two fingers in the sign to ward off the evil eye.

'Do not say such things, Signor Officer! No, the Prince is not – not what you said. It is said that he has suffered since childhood from a terrible affliction, and this is why no one has ever seen him. His parents never produced him in public and not long after he was born they went abroad and died there. He was brought back, alone – or at least with only the servants I spoke of who have been with him since his birth.'

The officer wagged his head, more impressed by this than he cared to admit.

'And he lives so still, shut away behind walls and bars, and servants?'

'Sometimes he goes away, to some other of his estates most probably, taking his major-domo and his chaplain with him, but no one ever sees him go or is aware when he returns.'

There was silence. The officer tried to laugh, to lighten the atmosphere. He turned to his friends who stood gaping uncomfortably.

'This Prince of yours is a joker! Or a madman! And we don't like madmen! If you say the Grand Duchess won't like it if we attack him, then we won't attack him. In any case, we've plenty of things to do besides that just at present. But we'll send word to Florence and' – his tone changed abruptly, the threatening note returned and he thrust his fist under poor Orlandi's nose – 'and if you have been lying to us, we'll not only go and dig your night bird out of his hole, but you'll feel the weight of my scabbard on your fat carcass! Come on, all of you! Our next call is the monastery of Monte Oliveto – Sergeant Bernardi, you stay here with your section! They're a bit too pious in this damned town. As well to keep on eye on them. You never know…'

The militia trailed out of the room in a great clatter of boots and sword belts. Orlandi turned to Marianne who had been waiting quietly, with Gracchus and Agathe peering avidly over her shoulder, for this bizarre scene to end.

'Signorina, excuse please, but I could not let these men attack the Villa Sant'Anna. It would have brought trouble for everyone, for them and for us.'

Curiosity impelled Marianne to find out more about the strange person whom the innkeeper had described.

'Are you really so much afraid of the Prince? Yet you yourself have never seen him?'

Orlandi shrugged and picking up a lighted candle from a side table turned to conduct the travellers upstairs.

'No, I have never seen him, but I have seen the good which is done in his name. The Prince is very generous to the poor and who knows how far his power may extend? I would rather he were left alone. We know his generosity, we do not yet know his anger – and what if he should indeed be in league with the Evil One…' Once again, Orlandi crossed himself three times in quick succession. This way, signorina. Your coachman's lodging shall be seen to and there is a small room for your maid next door to your own.'

In a moment he had thrown open a door and ushered Marianne into a chamber, simple but clean, with bare, whitewashed walls and furnished with a table, a pair of upright chairs and a long, narrow bed, its massive black wooden head so tall that it reminded Marianne uncomfortably of a tomb. There was also a large crucifix and a number of holy pictures. Except for the red, cotton counterpane and window curtains, the room might have been a convent cell. Jug and basin, made of thick green and white pottery, were shut away neatly in a cupboard and the whole room was dimly illuminated by a single oil lamp.

'My best room,' Signor Orlandi remarked with pride. 'I hope the signorina will be comfortable. Should I perhaps inform the Signor Zecchini?'

Marianne gave a little shiver. The story of the invisible Prince had in some degree taken her mind from her own troubles and from this mysterious individual who had been waiting for her since that morning. She thought she might as well find out at once who he was.

'Yes, tell him I am ready to receive him. Then you may bring us some food.'

'Does the signorina wish her baggage brought up?'

Marianne hesitated. She had no idea whether her godfather's plans for her included a lengthy stay at the inn, but she reckoned that her baggage would not suffer from one more night strapped to the coach.

'No, I do not know if I shall be staying. Just send up the big carpet bag from inside.'

When Orlandi had gone, Marianne took the precaution of despatching Agathe, who was practically asleep on her feet, to explore her own small chamber, a cubby-hole reached by a door in the corner of the room. Marianne told her not to come back until she was called.

'But – suppose I fall asleep?' the girl said.

'Then sleep well. I will wake you in time for supper. My poor Agathe, you had no idea this journey would prove such a penance, had you?'

Under her crumpled bonnet, Agathe smiled happily at her mistress. 'Oh it has been tiring, but ever so interesting. And I would go anywhere with mademoiselle. All the same, I can't say I think much of this inn. A nice fire would do no harm. It's that damp in here.'

Marianne's gesture of dismissal silenced her. There had been a light tap on the door.

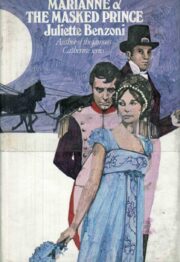

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.