'Truly. You did all you could have done. It is out of our hands now. Take this evening off, I shall not need you again tonight.'

Gracchus looked anxious. 'How have you managed without me all this time? You haven't got another man?'

Marianne smiled faintly. 'Simpler than that. I have merely stayed at home. You know I could not replace you.' And leaving the faithful Gracchus much comforted by this assurance, she went downstairs, only to find Jeremy waiting for her with an expression that seemed to presage the direst of catastrophes. Marianne was too well acquainted with his air of settled melancholy to be seriously deceived but tonight her nerves were on edge and Jeremy's long face was more than she could stand.

'Well?' she demanded. 'What is it now? Has one of the horses cast a shoe or has Victoire made an apple tart for supper?'

Instantly, the butler's mournful look changed to one of deep offence. With great solemnity, he turned and lifted a silver salver from a side table and proffered a letter to his mistress.

'If mademoiselle had not departed so hastily,' he murmured, 'I should have given mademoiselle this letter. A messenger, very dusty, brought it a short while before mademoiselle's coachman returned. I believe it to be urgent.'

'A letter?'

The single, folded sheet, sealed with red wax, had clearly travelled far, for the paper was stained and crumpled, but Marianne's fingers trembled as she took it. The seal was a simple cross but she recognized her godfather's hand. This letter was her sentence, a life sentence, crueller perhaps than a sentence of death.

Marianne walked slowly up the stairs, the letter still unopened in her hand. She had known that it must come one day but she had hoped against all hope that she would have her own answer. Now she was putting off the moment of opening it as long as possible, knowing that when she read it it would seem like an implacable decree of fate.

Reaching her own room, she found her maid, Agathe, putting away some linen in a drawer. One glance at her mistress's white face made Agathe exclaim: 'Mademoiselle is so pale! Let me take your outdoor things off first. And after that, I will fetch you a hot drink.'

Marianne hesitated for a moment then she laid the letter on her writing-table with a sigh.

It meant a few minutes' respite, but all the time Agathe was removing her street dress and half-boots and replacing them with a soft house dress of almond-green wool trimmed with bronze ribbons and matching slippers, her eyes kept turning to the letter. She picked it up at last and retired with it to her favourite chair beside the fire, feeling slightly ashamed of her childish weakness. As Agathe slipped noiselessly from the room with the clothes she had discarded, Marianne slid a determined finger under the seal and smoothed out the letter. It was brief and to the point. In a few words, the cardinal informed his god-daughter that she was to be at Lucca in Tuscany on the fifteenth of the following month and should take rooms at the Albergo del Duomo.

'You will have no difficulty in procuring a passport to travel,' the cardinal continued, 'if you declare your object as being to take the waters at Lucca for the sake of your health. Ever since Napoleon made his sister Elisa Grand-duchess of Tuscany he has looked favourably on those who wish to visit Lucca. Do not be late.'

That was all. Marianne turned the letter over in disbelief. What? Nothing more?' she murmured incredulously. 'Not one word of affection! No explanation! Merely instructions to present myself and advice about procuring a passport. Not one word about the man I am to marry!'

The cardinal must be very sure of himself to write in such terms. This meeting meant that her marriage to Francis Cranmere was already dissolved but it meant, in addition, that somewhere under the sun a stranger was preparing to marry her. How could the cardinal have failed to realize the terrors this stranger must hold for Marianne? Was it really so impossible to say a few words about him? Who was he? How old? What did he look like? What kind of man was he? It was as if Gauthier de Chazay had led his god-daughter by the hand to the entrance of a dark tunnel and left her there. It was true he loved her and desired her happiness but Marianne felt suddenly like a helpless pawn in the hands of an experienced player, an object to be manipulated by powerful forces in the name of the honour of her family. Marianne was beginning to find out that the freedom for which she had been fighting was nothing but an illusion, it had all been for nothing. She was once again the daughter of a great house, passively accepting a marriage which others had arranged for her. Centuries of pitiless tradition were dosing on her like a tombstone.

Wearily, Marianne tossed the letter into the fire and watched it burn before she turned to take the cup of hot milk Agathe brought for her, curling her cold fingers round the warm porcelain. A slave! She was no better than a slave! Fouché, Talleyrand, Napoleon, Francis Cranmere, Cardinal San Lorenzo: they could all do as they pleased with her. Life could use her as it would. It was pitiful!

Rebellion welled up in her. To the devil with that absurd promise of secrecy which had been extorted from her! She desperately needed a friend to advise her and for once she could do as she wanted! She felt choked with anger, misery and disappointment. She needed the relief of speech. She marched quickly to the bell-pull and tugged it twice, with decision. In a moment Agathe came running.

'Has Monsieur de Jolival returned yet?'

'Yes, mademoiselle, a moment ago.'

'Then ask him to come here. I wish to speak to him.'

'I knew there was something the matter,' was all Arcadius said coolly when Marianne had put him in possession of the facts. 'And I knew that you would have told me if it lay in your power to do so.'

'And you are not shocked? You are not cross with me?'

Arcadius laughed, although there was little gaiety in his laughter.

'I know you, Marianne. Your own distress when you are obliged to conceal something from a true friend makes it cruel as well as absurd to be angry with you. There was little else you could have done in the present case. Your godfather's precautions were fully justified. What are you going to do now?'

'I have told you: wait until the last possible moment for Jason and if he does not come – go to meet my godfather as he says. Do you see any alternative?'

To Marianne's surprise, Arcadius coloured violently, then rose and walked about the room in an agitated manner, his hands clasped behind his back. At last he came back to her, looking embarrassed.

There might have been an easier one for you. I know that my life has been unsettled but my family is a respectable one and you could have become Madame de Jolival without blushing for it. The difference in our ages would have protected you from any – any importunities on my part. I should have been more a father to you than a husband. Alas, it is no longer possible.'

'Why not?' Marianne asked gently. Arcadius's reaction had not taken her wholly by surprise.

Arcadius flushed scarlet and turned his back on her before he answered in a muffled voice. 'I am already married. Oh, it is old history now,' he added quickly. He turned back to her. 'I have always done my best to forget it but the fact remains that there is, somewhere, a Madame de Jolival who, whatever her title to that name, at least prevents me from offering it to any other.'

'But Arcadius, why did you never tell me? When I first met you in the quarries of Chaillot you were at odds with Fanchon Fleur-de-Lis because, if I remember rightly, she was trying to force you to marry her niece Philomena. She was actually keeping you a prisoner on that account. Why did you not tell her that you were married?'

'She would not believe me,' Jolival said pathetically. 'She even said that if it were so it need present no obstacle. They would merely be obliged to remove my wife. Now, I dislike Marie-Simplicie intensely – but not as much as that! As for you, I did not tell you the truth at first because I did not know you very well and I feared that your principles might forbid you to keep me with you; and you are so exactly the daughter I would have wished to have.'

Much moved, Marianne rose at once and going to her old friend slipped her arm affectionately through his.

'We are both equally guilty of deception, my friend! But you need not fear. I would not have lost you for the world; no one, since my aunt died, has taken such care of me as you have. Will you let me ask you one question? Where is your wife?'

'In England,' Jolival said gruffly. 'Before that, she was at Mittau and before that in Vienna. She was one of the first to flee when the Bastille was attacked. She was a close friend of Madame de Polignac while I – well, our political ideas could not have differed more.'

'And – you had no children?' Marianne asked, almost timidly, but unexpectedly Jolival laughed.

'It is clear that you have never set eyes on Marie-Simplicie. I married her to please my poor mother and to settle an interminable family squabble, but I assure you that it went no further than my name! Besides, quite apart from her ugliness, her pride and her religion would probably have made her shy from such gross, animal contact as we call love. She is at present one of the ladies-in-waiting to the Duchess of Angoulême and, I am sure, perfectly happy, from what I hear of that princess. They can join together in praying to God to confound the Usurper and restore France to the delights of an absolute monarchy, so that they can return to Paris to the cheerful clatter of chains as the leaders of the Empire are led off to the galleys! She is a very gentle, devout woman is Marie-Simplicie.'

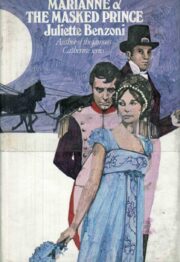

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.