There was only one bright spot in the prevailing gloom. Napoleon had sent her a short note from Compiègne and the handwriting quickened her blood although the contents were a disappointment.

'My dear Marianne, a brief word to let you know that you are still in my thoughts. Take care, your health is important to me, as is the voice which, when I return from my travels, shall once more alleviate the cares of State which weigh on your N.'

The weight of the cares of State, indeed! The Emperor's 'dear Marianne' knew from Arcadius, who was far from sharing her seclusion, that he was a great deal more occupied with his honeymoon and the pleasures of his court than with affairs of State. It was all balls, hunting, picnics, theatres and diversions of every kind, and apart from presiding once over the Council of the Imperial Household and one audience with Murat concerning affairs in Italy, the Emperor had done very little. It was kind of him to have written, of course, but Marianne merely tossed it on to the mantelpiece with a sigh and thought no more about it, a thing which would have been unthinkable a few weeks earlier.

Even her panic fear inspired by Lord Cranmere's escape took second place to her longing for Gracchus to return, bringing word of whether she could hope for Jason's arrival. She no longer shuddered at every strange sound in the night, no longer flinched at the sight of a stranger in the street who reminded her of the Englishman. She knew that Jason's coming would be the best cure for her fears. If he consented to take her under his protection for always, she would no longer fear the threats of ten Francis Cranmeres. Jason was strong and bold, the kind of man who could make one glad to be a woman. He must come, he must. But, oh God, the time of waiting seemed long!

There was one person, apart from the faithful Jolival, whom Marianne would have been glad to see and that was Fortunée Hamelin. The panic which had filled her at the news of Francis's escape had faded but Marianne had thought long and deeply about it. She had no details, but it was clear that it could not have happened without the tacit consent of the Minister of Police. Yet it seemed to her impossible that one of Napoleon's ministers could stoop so low, as to baulk the efforts of his own agents, and release a dangerous criminal who was also a deadly enemy of his country.

Fortunée, who knew so many things, might have been able to elucidate the mystery but Fortunée was not at hand: caught up afresh in her passionate affair with the handsome Fournier-Sarlovèze, she had vanished from sight just as her black butler Jonas had predicted.

Marianne thought dejectedly that both the women whom she really trusted, the only two she really cared for, had been swept off their feet by the irresistible power of love. She alone was left with a lover who was worse than useless and who seemed for the moment at least to have abandoned her.

Napoleon had said one day, quoting Ovid and laughing, that love was a kind of military service. For Marianne it was worse than that. It was like entering a convent with solitude and memory for her only companions.

Then one morning at breakfast-time, Monday the nineteenth of April by Marianne's calendar, Fortunée descended without warning on her friend. Haphazardly dressed, with her hair in a disorder she embraced Marianne abstractedly, told her she was looking blooming, which was a manifest exaggeration, and sank down in a chair, calling Jeremy to send her a big pot of coffee, very strong with lots of sugar.

'You had better drink chocolate,' Marianne observed, alarmed by the possible effects of coffee on someone visibly suffering under strong agitation. 'Coffee is very stimulating to the spirits, you know.'

'I need stimulating. I want to be excited and enraged! I want to keep my anger on the boil!' Fortunée declared dramatically. 'I don't want to forget the perfidy of men. Remember this, my poor sweet. Believe what a man tells you and you may as well listen to the wind! Even the best of them are abject monsters and we are their pitiful victims.'

'Do I gather that your hussar has been making victims?' Marianne inquired, feeling Fortunée's fury like a breath of fresh air.

'He is a wretch!' Fortunée declared forcefully, helping herself to a substantial portion of scrambled egg and several slices of bread and butter. 'Just imagine, a man I have loved for years, whom I have nursed day and night with nun-like devotion, and to do that to me!'

Marianne bit back a smile. The last time she had seen Fortunée and the handsome Fournier, on the evening of the Emperor's wedding, her behaviour had been anything but nun-like.

'What?' she asked. 'What has he done?'

Fortunée gave a sharp, mirthless little laugh. 'A mere nothing! Can you credit it, he dared to bring that Italian female with him to Paris?'

'What Italian?'

'Some girl from Milan – I don't know her name! The stupid creature fell in love with him there and left everything, fortune and family, to go with him. I had heard that he had brought her back with him and installed her in a house of his at Sarlat, in Périgord, which is where he comes from, but I would not believe it. And now it seems that she was not only at Sarlat but has actually come here with him! It is too much!'

'How did you find out?'

'He told me himself! You can have no idea of the depths of his cynicism. He left me last night, merely saying that it was time he rejoined her as she must be in some anxiety about him! He had actually dared to send her a message from my house to the effect that he was hurt and was being cared for in a place where he could not send for her to come. I threw him out, as I hope she will do as well, the baggage!'

This time Marianne was unable to help herself. She dissolved in helpless laughter and was conscious of a feeling of strangeness as she did so. It was the first time she had laughed in three weeks.

'You should not fly into such a passion. If he has been shut up with you for a fortnight, he must need rest and sleep more than anything. And after all, he was still a sick man. Let him go back to his Italian. If they are living together she must be in some sort his wife and yours is really the better part. You can abandon him to the delights of his fireside.'

'Fireside? Him? It is clear you do not know him. Do you know what he asked me as he left?'

Marianne shook her head. It was best that Fortunée should continue in ignorance of her encounter with Fournier.

'He asked for your address,' Fortunée said triumphantly.

'Mine? But why?'

'To call on you. He thinks that your "vast influence" with the Emperor will enable you to obtain his reinstatement in the army. In which he is greatly mistaken.'

'Why so?'

'Because Napoleon dislikes him enough already, without adding to his dislike with suspicions about the precise nature of his relations with you.'

That much was obvious, and moreover Marianne had no desire for a further meeting with the ebullient general with his bold eyes and over-ready hands. Considering the manner of their first meeting, it was decidedly impudent of him to have dared to think of asking her help. Besides, she was tired of men who always wanted something, who never gave anything for nothing. Consequently it was with considerable dryness that she said: 'I am sorry to have to say this, Fortunée, but I should on no account do anything for your hussar. In any case, God alone knows when I shall see the Emperor again.'

'Good for you,' Fortunée approved. 'Leave my admirers to their own devices. You have little enough to thank them for, it seems.'

Marianne's eyebrows rose. 'What do you mean?'

'That I am perfectly aware of the despicable way Ouvrard behaved towards you. Well, Jonas has remarkably sharp ears you know, and he is not above listening at keyholes.'

The colour flamed in Marianne's face. 'Oh!' she said. 'You knew? You said something to Ouvrard?'

'Not a word! But it will keep. You need not worry, I shall find a way to take revenge for both of us, and before very much longer. As for you, I would go through fire for you if need be. You have only to say the word. I am yours body and soul! Do you still need money?'

'No, not now. It is all right.'

'The Emperor?'

'The Emperor,' Marianne agreed, suppressing a twinge at this fresh lie. She did not want to tell Fortunée about her meeting with her godfather and what had followed.

She had given her word not to talk about her dreadful situation, about the child that was coming and the marriage to which she had been obliged to consent, and ultimately it was better so. Fortunée would not have understood. Her religious feelings were superficial, not far removed from paganism. She was a Creole, careless and shameless, and she would have flaunted an army of bastards in the world's eyes without a blink if nature had not decreed otherwise. Marianne knew that she would have opposed the cardinal's plans with all her strength and it was not difficult to guess what her advice would be. She would counsel her friend to tell Napoleon of the coming event and let him marry her off to the first man who was fool enough to take her – and then console herself with all the lovers she could get her claws in. But not even to save her honour and her child's would Marianne consent to give her hand to a man motivated by base self-interest. There was nothing base about Jason and she knew her godfather well enough to be sure that any man chosen by him would not marry her for the sake of any such calculations. From every point of view it was better to say nothing to her friend. There would be time enough afterwards – or at least when Jason had come, if he came…

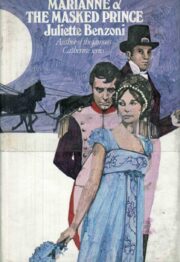

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.