The thought brought with it a sense of relief, a new serenity, and that night Marianne slept like the child she had been so short a time ago. What was more blessed than peace of mind? And for three days and three nights Marianne enjoyed it to the full, together with a pleasurable feeling of having won a victory over both Francis and herself.

An idea came to her during those days and she hugged it to her lovingly. If Black Fish succeeded in removing Francis from the face of the earth, then there would be no need for an annulment, or for the threatened marriage. She would be a widow, free, with nothing more to fear from Francis Cranmere, free to join with the father of her child in seeking a less desperate remedy for her situation.

A hundred times she was on the point of picking up her pen and writing to her godfather but each time one thing stopped her. Where should she write? To the Pope at Savona? The letter would never reach him. It would surely fall into Fouché's hands. No, it was better to wait for word to come from the cardinal. Time enough then to tell him what had occurred and he might be the one to offer another solution. It was so good to dream, to make plans that were not dictated by necessity.

On the morning of the fourth day all these dreams were shattered into fragments. The blow came in the form of a single sheet of white paper, carefully folded and sealed, brought by Agathe to her mistress as she lay in bed. Marianne read it and flung back the covers with a cry of anguish. Barely pausing to catch up a dressing-gown in passing, she tore downstairs, barefoot, to where Jolival was peacefully enjoying his breakfast in the company of the morning's papers. When Marianne burst in on him, white-faced and clearly in a state of terror, he sprang to his feet so suddenly that the table at which he had been sitting tottered and fell with a crash, taking the breakfast things with it. Neither of them so much as glanced at this miniature cataclysm of broken china. Marianne was holding out the letter speechlessly. She dropped into a chair and signed to Jolival to read it.

In a few hurried, angry lines, Black Fish apprised his young friend of Lord Cranmere's escape from Vincennes. How he had contrived it was a mystery. His trail led to the Boulogne road and thence, no doubt, to England. The Breton added that he was about to set out in pursuit. 'And the devil help him when I get my hands on him,' he wrote. 'It will be him or me.'

Arcadius had himself more under control than Marianne but even he blenched. Crumpling the letter in his fist he cast it into the hearth, then turned his attention to the girl, who was lying back in her chair with closed eyes and livid complexion, breathing unevenly and apparently on the verge of fainting. Arcadius administered two or three brisk slaps to her cheeks before seizing her cold hands and rubbing them hard.

'Marianne!' He spoke in agonized tones. 'Marianne, don't. Open your eyes! Look at me! Marianne —'

She raised her eyelids, showing her friend eyes that were two dark pools of terror.

'He is free…' she muttered. 'They have let him escape – they have let that monster go free, and now he will give me no peace. He will come here, seeking vengeance – he will kill me. He will kill us all!'

Her voice was shrill with fear. Arcadius had never seen Marianne like this. She was always so brave, so ready to face any peril, yet these few words had driven her to the brink of madness. He realized that the only way to save her was to be cruel, make her ashamed of her panic. He stood up, letting fall the hand he held.

'Is it for yourself that you are afraid?' he said harshly. 'Don't you understand what Nicolas Mallerousse says? The man has escaped, yes, but he is making for England where I dare say he will return to his hobby of hunting down escaped prisoners. Since when have your fears been for yourself, Marianne d'Asselnat? You are in your own house, surrounded by faithful servants, men like Gracchus and myself who are your devoted friends! You can command the aid of the man who holds all Europe in his hands and you know that the man you fear is hunted by an implacable enemy. And are you afraid for yourself? You should be thinking rather of those poor wretches who must once again face a hideous death in their efforts to escape…'

As he spoke, using his voice like a whiplash, Jolival saw Marianne's eyes begin to clear and fill, first with disbelief and then, little by little, with the shame that he was waiting for. He saw the colour creep back into her white cheeks and deepen to a blush. She sat up and the hand she passed across her face barely trembled. Another moment and:

'Forgive me,' she said in a low voice. 'I am sorry. I lost my head. You are quite right – as always. But when I read that letter, just now, I felt as if my head would burst. I thought I was going mad. You can't understand.'

Slowly, Arcadius knelt beside her and placed both hands gently on her shoulders.

'Yes, I can guess. But I will not let you destroy yourself because of this man's shadow. By now he is probably a long way away and he has to save his own life before he can attack yours.'

'He may come back very soon, in disguise.'

'We will be watching.'

'He is stronger than we are. See how he managed to escape – in spite of walls and chains, the massive gates, the guards and even Black Fish.'

Arcadius got up and began mechanically setting the table to rights. His mouselike countenance was grave.

'It is true. I was wrong. But how could anyone have guessed that Fouché would dare? What is the Englishman's part in the political web he is weaving?'

'A very important one, no doubt.'

'No political scheme is important enough to merit leaving a fiend at large, Marianne! The Emperor must be warned.'

'Warned? Of what? That a spy has escaped from Vincennes? He must know that by now.'

'I doubt it. He would want to know why. I hardly think it will be mentioned in Fouché's daily report. Go and see him – tell him everything – and trust in God!'

'The Emperor is away.'

'He is at Compiègne, I know. Go there —'

'No. When I said he was away, I was thinking of myself. He does not wish to see me at present – later, perhaps. I told you how we parted.'

'Go, even so. He loves you still.'

'Perhaps, but I do not care to risk it. Not just now. I should be too frightened, frightened of making another mistake. No, Arcadius, let us leave him to his honeymoon, let him make his tour of the northern provinces. When he returns, maybe… Wait and see how matters turn out. We must trust in Nicolas Mallerousse. He hates him too much to fail.'

With a sigh, Marianne rose and, kicking aside the fragments of the Sevres coffee-pot, went to the mirror. Her face looked pale and hollow but her eyes had recovered their old assurance. The battle had begun again and she had tacitly accepted it. Fate would decide.

She was half-way to the door when Jolival asked, almost timidly: 'You really mean to do nothing? You will wait?'

'I have no alternative. You yourself told me that these secret negotiations of Fouché's could be a blessing for France. That is worth the risk of a few lives – even mine.'

'I know you, Marianne. You will show a serene face to the world but inside you will be scared to death.'

She had reached the door before she turned to him with a faint smile.

'That may well be, my friend. But one grows accustomed to it, you know. One grows accustomed.'

CHAPTER EIGHT

The Long Wait

Time seemed to stand still. To Marianne, confined to the house as much from prudence as from a lack of any inclination to go out, day followed day unvaryingly. The only change was that each day seemed longer than the one before. Uncertainty gnawed at Marianne, like water wearing away a stone, making the waiting an agony.

Gracchus had been gone for more than a fortnight and the reasons for his continued absence were a mystery. If he had ridden day and night, as he had declared his intention of doing, he should have reached Nantes very quickly, in three days at most. After handing the letter to the United States consul, he should have been back within a week or so. Then why this delay? What had happened? Marianne spent her days at the window of the little sitting-room on the first floor overlooking the main courtyard and the rue de Lille. The sound of a horse's hooves would set her heart beating faster, leaving disappointment behind when they passed on and died away. It was worse still when they stopped and were followed by the slightly cracked sound of the front door-bell. On these occasions Marianne would hurl herself at the window only to draw back at once with tears pricking at her eyes because it was not Gracchus.

The nights became steadily more terrible. Marianne slept little and badly. She spent the endless sleepless hours building up all kinds of fantastic theories, each wilder than the last, about what had happened to Gracchus. The worst of these, which left her trembling and bathed in sweat on her burning hot pillows, was that the unfortunate youth had been set on by the highwaymen who still infested the roads in spite of the vigilance of the imperial police. A solitary horseman was an easy victim and there were plenty of places where a body could be left lying unnoticed in the undergrowth for many weeks. Marianne was tormented by the thought that if anything had happened to her faithful coachman no one would come to tell her. She might be waiting in vain for the return of a loyal friend and for a reply which would never come.

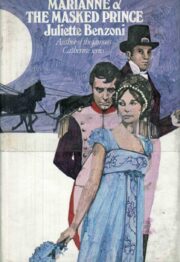

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.